| 2005 Case #1 |  |

|

| (Links to Other 2005 Cases are at bottom of this page) | ||

| Diagnosis: The acute form of bartonellosis due to Bartonella bacilliformis. Also known as Oroya fever and Carrion's Disease. |

Discussion: The blood film showed no malaria but overall >95% of the red blood cells contained small pleomorphic coccobacilli intracellularly which are diagnostic of acute bartonellosis. Blood cultures using Columbia agar were drawn but must be incubated at 25-28°C and take up to 2-4 weeks to become positive. Western blot (pending) and PCR are most useful for diagnosis of the chronic eruptive form of the disease (see below) where blood films are usually negative but are generally unnecessary in the acute form where, on average, over 60% of erythrocytes have intracellular bacteria. Discussion: The blood film showed no malaria but overall >95% of the red blood cells contained small pleomorphic coccobacilli intracellularly which are diagnostic of acute bartonellosis. Blood cultures using Columbia agar were drawn but must be incubated at 25-28°C and take up to 2-4 weeks to become positive. Western blot (pending) and PCR are most useful for diagnosis of the chronic eruptive form of the disease (see below) where blood films are usually negative but are generally unnecessary in the acute form where, on average, over 60% of erythrocytes have intracellular bacteria.

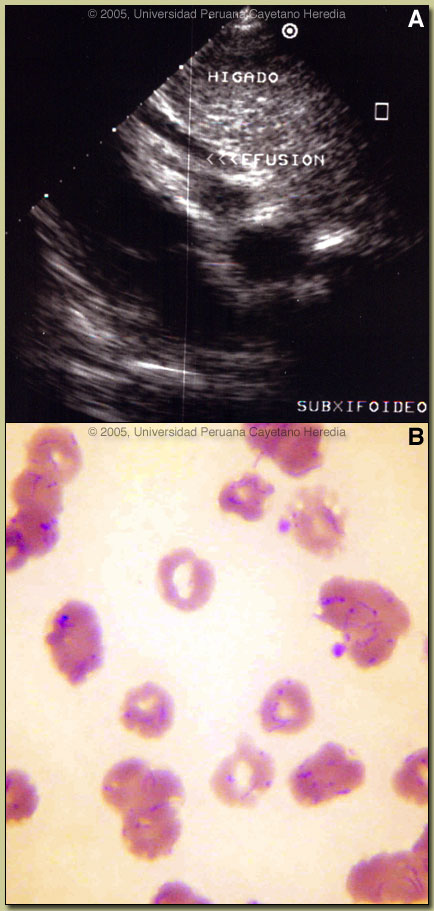

Clinically the acute phase of infection follows an average 17-day incubation period. Almost all patients have fever, malaise, and anorexia. Pallor is usually noticeable, in hospitalized cases anyway, as the average admission hematocrit is 17%. The anemia is due to red-cell lysis and not autoimmune in nature as the Coombs test is uniformly negative. Hepatomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and jaundice each occur in about 3/4 of cases but splenomegaly in only about 1/4. A significant number of patients may develop congestive heart failure, pericardial effusion, or anasarca. Neurologic complications of uncertain etiology occur in about 20%; manifestations include altered mental status, ataxia, agitation, or even coma. Our patient?s confusion resolved after 3 days of antibiotic therapy in hospital. A secondary immunosuppression may lead to subsequent or concomitant salmonellosis (both S. typhi and non typhi), toxoplasma reactivation and occasionally other opportunistic infections have been seen. In those untreated patients that have inapparent acute phases or survive the primary infection, a chronic eruptive phase occurs. Skin lesions, called Verruga Peruana, are most commonly miliary in nature with multiple 1-4 mm papular, erythematous round lesions that are often pruritic. Image C shows an example from our files. These are loaded with bacteria and are histologically similar to HIV related bacillary angiomatosis lesions caused by the related organisms B. henselae and B. quintana. Bartonella henselae is also the agent of cat-scratch disease. The distribution of Bartonella bacilliformis, which is transmitted by the bite of the Lutzomyia verrucarum sandfly is restricted to the inter-Andean valleys of Perú and Ecuador. The railway between Lima and La Oroya high in the Andes was one of the engineering feats of the 19th century, but thousands of workers died of bartonellosis (hence the name Oroya Fever) during construction. This was a prominent problem in building the aptly named Verruga Bridge [Image D; 2005 Gorgas Expert Class field trip this past weekend]. Classically, transmission was thought to be restricted to 500-2500 meters elevation and between 2-13 degrees latitude in these 2 countries, but more recently cases have been described up to 3200 meters. Of importance to travel medicine physicians, a new focus has been described in the last 6 years in the Urubamba Valley of Perú. So far this focus has not impinged on the portion of that valley traversed by visitors to Machu Picchu, one of the major tourist destinations in South America. Travelers are more likely to encounter bartonellosis when trekking out of Huaraz (where this patient acquired his infection) in the Cordillera Blanca region of the country. Recent in vitro data confirm that B. bacilliformis is sensitive to most antibiotics including penicillins (including Penicillin G and ampicillin), cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, chloramphenicol, macrolides, tetracyclines, and quinolones [Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004 Jun;48(6):1921-33]. Ceftriaxone has the best MIC values of all antibiotics tested. In the past chloramphenicol has been used extensively in Perú because of its ability to simultaneously cover concomitant opportunistic salmonellosis. Because of increasing salmonella resistance to chloramphenicol and toxicity concerns with this drug, Ciprofloxacin 500 mg po bid for 10 days is now the first line therapy, although clearly almost any available antibacterial agent will suffice for the bartonellosis itself. Because our patient was so severely ill, he was treated with both Ciprofloxacin and Ceftriaxone intraveneously for 10 days. In addition he received 2 units of packed red cells. The bartonella and malaria endemic areas of Per? have little overlap. In a traveler to Perú with fever and anemia, the first diagnosis is malaria if they have been to low lying jungle regions but the first diagnosis should be bartonellosis if travel has been restricted to inter-Andean valleys. Untreated bartonellosis will almost always be fatal in a traveler. Antimalarials are not effective against bartonellosis. Always rule out malaria in a tropical traveler to endemic areas but it is important not to let a patient with possible bartonellosis die for lack of a little ciprofloxacin or penicillin. Reference: Maguina C., et al. Bartonellosis (Carrion's Disease) in the Modern Era. Clin Infect Dis. 2001 Sep 15;33(6):772-9.

|