|

Gorgas Case 2025-11 |

|

|

This is the last case of the week of 2025. The cases have been selected and edited by the Directors and Clinical Coordinator of the Courses. We want to express our gratitude to everyone involved in preparing these cases. We will post new cases in 2026.

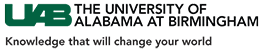

History: A 73-year-old female patient with a past medical history of arterial hypertension presented with a 2-month history of polyarthralgias and subjective fever. Two months before admission, while in Santa Cruz, Bolivia, the patient began experiencing a subjective fever accompanied by chills. One day following symptom onset, she developed severe joint pain involving both wrists, shoulders, and ankles. Two days later, she reported decreased appetite, nausea, vomiting (4–5 episodes per day), and watery diarrhea (6–7 episodes per day). On day 3 of illness, the patient developed localized swelling over the dorsum of the right foot. She received symptomatic treatment with minimal pain relief. One month before admission, the patient experienced severe upper limb pain, which impaired her ability to raise her arms or hold objects, along with intense ankle pain that significantly limited walking. She was evaluated at the rheumatology service and subsequently referred to our outpatient clinic. Epidemiology: The patient was born and currently resides in Lima. She currently has no occupation. She traveled to Santa Cruz, Bolivia, from March to June of the present year to visit her son. There, she reports visiting many tourist attractions, including areas of the highlands and the jungle, where she sustained numerous mosquito bites. Physical Examination on admission: BP: 130/80, RR: 18, HR 87, SpO2: 97% on room air. Musculoskeletal examination revealed tenderness on palpation of the metacarpophalangeal joints, decreased grip strength, and pain with passive and active movement of both shoulders. Additionally, tenderness was noted on palpation of the popliteal region, both knees, and both ankles. The patient presented with difficulty walking due to persistent pain. The rest of the exam was non-contributory. Laboratory: Hemoglobin 12.9g/dL, Hematocrit 36.2%, Platelets 222000, WBC 4500, /µL; with bands 1%, neutrophils 49%, eosinophils 5%, basophils 0%, monocytes 0%, lymphocytes 45% Glucose 88 mg/dl, Urea 42 mg/dl, total proteins 7.15 g/l, albumin 4.07 g/l. The urine exam was normal. An Ultrasound examination demonstrates bilateral synovitis involving the wrist joints and popliteal regions, characterized by joint effusion and synovial thickening. Additionally, there is evidence of bilateral tenosynovitis of the Achilles tendons, characterized by hypoechoic peritendinous fluid and thickening of the synovial sheath. Evaluation of the hindfoot reveals retrocalcaneal bursitis, manifested by distention of the retrocalcaneal bursae with anechoic fluid (IMAGE A, see arrow). UPCH Case Editors: Carlos Seas, Course Director / Paola Nakazaki, Associate Coordinator |

|

Discussion: The skin scrape microscopy shows structures typical of Sarcoptes scabiei. An ELISA test for detecting IgM antibodies against the Chikungunya virus was positive. Chikungunya virus is an arthropod-borne alphavirus in the Togaviridae family, transmitted by mosquitoes, mainly Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. It was first identified in East Africa during the 1950s. It was called kungunyala, meaning “to walk bent over” or “to become contorted,” due to the severe pain often associated with the illness (1). Chikungunya is now widespread across tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Asia, the Americas, and, to a lesser extent, Europe, primarily through travel-related cases (2). The incubation period typically ranges from 2 to 6 days. Less than 15% of infected individuals remain asymptomatic. At the same time, most individuals develop symptoms, typically starting with fever and malaise, which can be accompanied by musculoskeletal manifestations that may even precede fever, such as arthralgias and myalgias, or dermatologic involvement. In most cases, this includes an erythematous maculopapular rash that primarily affects the trunk but can also extend to the face and extremities (3). Arthralgias are usually bilateral and more often affect distal joints, with hands, wrists, and ankles being the most commonly involved areas. They may also be accompanied by tenosynovitis or periarticular swelling. The acute phase typically lasts between 1 and 2 weeks, characterized by a high-grade fever that typically lasts for three to five days. Musculoskeletal symptoms may persist chronically in around 30% of cases (4,5). Less common manifestations include lymphadenopathy, pruritus, and gastrointestinal symptoms, which can appear after viremia has resolved (3). Chikungunya infection should be clinically suspected in patients with epidemiologic exposure, considering the differential diagnosis of other conditions such as dengue fever, oropouche, Zika virus, leptospirosis, malaria, and rheumatoid or reactive arthritis. The diagnosis is established by PCR detection of chikungunya viral RNA, especially in those who present within the first week of symptom onset, or by serology in patients with symptoms lasting more than one week. ELISA can detect IgM within five days of symptom onset and can persist for weeks to months (3,6). There is no specific antiviral treatment for chikungunya virus infection. Management is supportive and symptomatic. The main aspects of therapy include rest, proper hydration, and relief of fever and joint pain with acetaminophen. NSAIDs can be used for persistent arthralgia after confirming dengue has been ruled out. For patients who develop chronic arthritis or arthralgias, corticosteroids and certain antirheumatic drugs, such as methotrexate, have been effective in small, randomized trials and observational studies (7,8). Currently, there are two approved vaccines: a live-attenuated vaccine (IXCHIQ) indicated for adults 18 and older, and a virus-like particle vaccine (Vimkunya) for individuals 12 and older. Protection against infection is 40%, and against disease is 70%. The vaccines are mainly recommended for travelers and laboratory workers; they are also used in areas where outbreaks have been identified. The IXCHIQ has caused serious adverse events in people 60 and older. The FDA, CDC, and EMA have ceased their indication for that age group, and the WHO has taken a cautious stance. Our patient sought care at our Institute after 2 months of symptom onset due to persistent pain that caused difficulty walking (VIDEO A), decreased grip strength (VIDEO B), and impacted her ability to perform daily activities. She is part of the subset of patients who continue to have chronic musculoskeletal involvement. She received symptomatic treatment with orphenadrine and celecoxib, and a drainage procedure was performed on the fluid in the retrocalcaneal bursae, as previously described in the ultrasound, with reported pain improvement at the follow-up visit. References |

|

Gorgas Case 2025-10 |

|

|

The following patient was seen in the Department of Infectious and Tropical Medicine at Hospital Cayetano Heredia during the 2025 Gorgas Advanced Course.

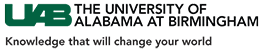

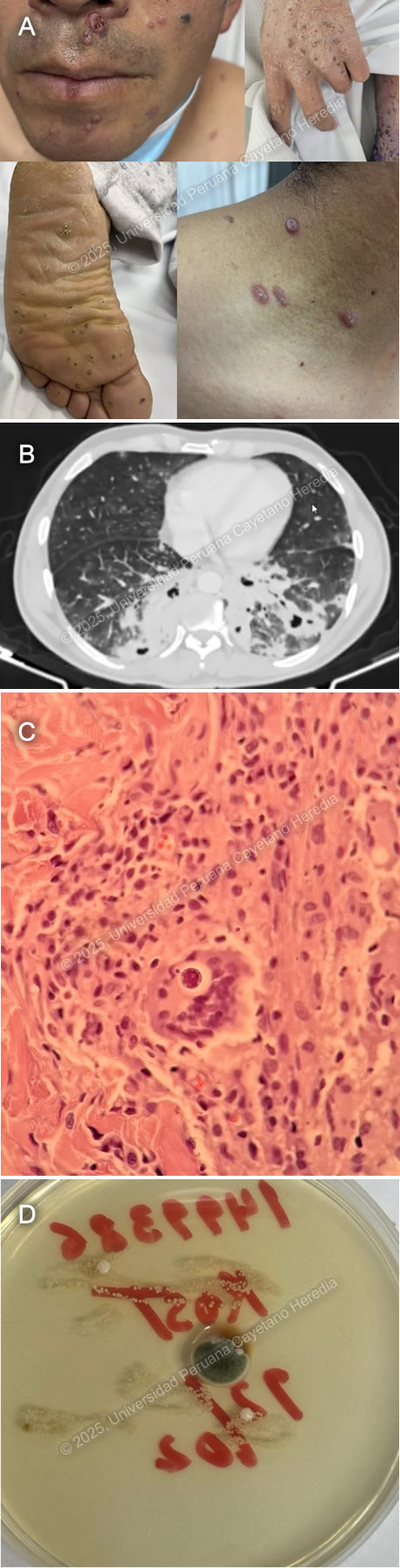

History: A 68-year-old male patient with a history of benign prostatic hyperplasia presented to the emergency department with a 7-month history of scaly skin lesions spread across the body, along with severe itching. Seven months prior to admission, the patient developed itchy, scaly lesions on both lower legs. Six months before admission, similar lesions appeared on the upper extremities and chest, accompanied by worsening itching. The skin lesions gradually spread, eventually covering the entire body surface. Initially, he was presumptively diagnosed with psoriasis at another facility and was started on oral medication with no clinical improvement. The lesions on his feet and hands became painful and limited his mobility, prompting him to seek emergency care. Epidemiology: The patient was born in Ancash, a city located at 3,052 meters above sea level in the highlands of Peru, where he lived until he was 5 years old. He currently resides in Lima. He reports traveling regularly through the jungle since 1980. He works as a cleaning staff member at churches. He reports frequent alcohol consumption and use of inhaled drugs. Physical Examination on admission: BP: 130/60, RR: 17, HR: 94, Sp02 98% on room air, T 37.6°C. The patient was not in acute distress. Thick, whitish, crusted plaques with an erythematous base, some exhibiting surface fissures and erosions, were seen on the arms, anterior chest wall, and abdomen. The palmar surfaces revealed several scaly papules and plaques involving the palmar creases. Fingernails exhibit nail dystrophy, onychorrhexis, and thickening of the nail plates. All toenails demonstrated nail plate thickening, onychodystrophy, and xanthonychia. (Images A,B,C,D). The rest of the exam was non-contributory. Laboratory: Hemoglobin 12.8g/dL; hematocrit 37%; WBC 36000/µL with bands 0%, neutrophils 70%, eosinophils 14% (absolute 1900/µL), basophils 0%, monocytes 7% and lymphocytes 9%. Platelets 406000/µL. Creatinine 0.95 mg/dL; urea 33 mg/dL; AST 24 IU/l; GGT 18 IU/L. INR was 1.14. Glucose 112 mg/dL; sodium 137 mEq/l; potassium 3.86 mEq/l, and chloride 102 mEq/l. Serology for HIV, hepatitis C, and hepatitis B were negative. The HTLV-1 chemiluminescent immunoassay was positive. Chest X Ray was non-contributory. Skin scrape microscopy is shown in Images E,F. UPCH Case Editors: Carlos Seas, Course Director / Paola Nakazaki, Associate Coordinator |

|

Discussion: The skin scrape microscopy shows structures typical of Sarcoptes scabiei. The Human T-cell Lymphotropic Virus type 1 is a retrovirus of the Retroviridae family. First identified in the early 1980s, it is known to exhibit a strong tropism for CD4+ T lymphocytes and establishes a persistent, lifelong infection in the host (1). Transmission occurs primarily through vertical routes such as breastfeeding, as well as through horizontal mechanisms including sexual contact, blood transfusion, and intravenous drug use (1,2). HTLV-1 infection is a neglected tropical disease with an estimated prevalence of 5 to 10 million carriers globally. It is endemic in certain regions, including southwestern Japan, the Caribbean, parts of South America, sub-Saharan Africa, and areas of the Middle East and Australia. Despite its clinical significance, HTLV-1 remains under limited public health surveillance and lacks effective antiviral therapies or vaccines (1,3). Although many infected individuals remain asymptomatic, the virus can cause severe diseases such as adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) and HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP). HTLV-1 infection induces a chronic state of immune dysregulation, predominantly affecting cell-mediated immunity via alterations in CD4⁺ T-cell subset polarization, impaired cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses, and dysregulated cytokine networks. These immunologic perturbations predispose individuals to a distinct spectrum of infectious diseases, many of which exhibit increased severity, chronicity, or dissemination in the context of HTLV-1 seropositivity (1). The most well-established and clinically significant association is with Strongyloides stercoralis with a marked increased risk of developing the hyperinfection syndrome (see Case of the Week 03-2012), characterized by uncontrolled proliferation and dissemination of larvae, often leading to severe gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and systemic complications (4, 5). An increasingly recognized clinical association exists between Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis hyperinfestation, commonly referred to as crusted scabies, and HTLV-1 infection, as its immune dysregulation contributes to both susceptibility and severity of infestation (6). The extreme mite proliferation, reaching millions per host, renders the condition highly contagious, with transmission possible via minimal direct contact or fomite exposure. It is characterized by extensive hyperkeratotic skin lesions, often with overlying crusts and fissures that can be distributed across the scalp, face, trunk, extremities, and periungual regions. Nail dystrophy and subungual hyperkeratosis are frequently observed, and in severe cases, the infestation may extend to mucocutaneous junctions. It can be accompanied by pruritus; however, it can be absent or attenuated due to blunted inflammatory responses in individuals with impaired cell-mediated immunity. Crusted scabies presentation can also mimic other dermatologic conditions such as psoriasis, eczema, or keratoderma, complicating clinical diagnosis (7). During hospitalization, our patient presented with fever, and developed Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) bacteriemia. Secondary bacterial colonization, often with Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes, is a common case of crusted scabies and can precipitate systemic sequelae, including bacteremia and sepsis (7). Currently, there is no curative or antiviral therapy available that can eliminate HTLV-1 infection. Management is therefore focused on treating HTLV-1–associated diseases and providing supportive care. Treatment approaches vary significantly depending on the clinical manifestation, most notably adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL), depending on the clinical subtype, and HTLV-1–associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP), with limited evidence (8, 9). Prophylactic antiparasitic therapy with ivermectin is recommended in endemic areas to prevent Strongyloides hyperinfection (5). Public health strategies focus on preventing transmission, including blood donor screening, avoidance of breastfeeding by infected mothers, and safe sexual practices (1). Monitoring the proviral load, neurological progression, and oncogenic transformation is essential in long-term management. Treatment should be combined with environmental decontamination and isolation precautions to prevent the transmission of the disease. Our patient was started on ivermectin for 3 days and repeated the dose for three more days. One week later, permethrin 5% was applied to the lesions all over the body daily. MSSA bacteremia is being managed with oxacillin. References |

|

Gorgas Case 2025-9 |

|

|

The following patient was seen on the inpatient ward of Cayetano Heredia Hospital in Lima by the 2025 Gorgas Course participants.

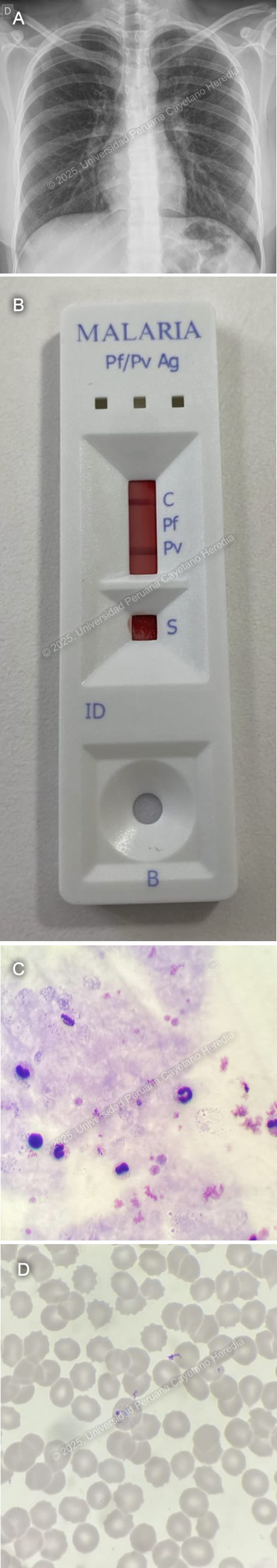

History: An 18-year-old female with a past medical history of polycystic ovarian syndrome and atopic dermatitis presented to the emergency department of Cayetano Heredia Hospital (HCH) with a 5-day history of fever, generalized malaise, and headache. Five days before admission, she abruptly developed fever with shaking chills, generalized malaise, bilateral oppressive headache, generalized weakness and diffuse myalgias, nausea, and vomiting. Four days before admission, fever persisted throughout the day and worsened at night. Two days before admission, she saw dark urine. On the day of admission, symptoms had progressively worsened, including food intolerance for which she attended the ED at HCH and was admitted for further workup and management. She denied abdominal pain, retro-ocular pain, calf pain, arthralgias, or skin or mucosal bleeding. Epidemiology: The patient currently lives in Lima but was born in Iquitos, a city located in the northern jungle of Peru, where she lived until her 17th birthday. Thirteen days before admission (8 days before symptom onset) she came back from an 8-day trip to Iquitos, where she worked with her father in an Indigenous community located in Requena province, 6 hours away from the city by boat, where she slept in tents, walked barefoot through the jungle, swam in the river and had inconsistent use of repellent and mosquito nets and had exposure to multiple wild animals. Physical Examination on admission: BP: 110/70 mmHg, HR: 110, RR: 18, T: 38°C, SpO2 98% on room air. The patient seemed to be in a stable condition. Skin exam revealed multiple scars from mosquito bites in both legs but no skin or conjunctival jaundice, pallor or bleeding. She had no palpable lymph nodes. She had normal breath sounds bilaterally with no crackles or wheezes. There was tenderness to deep palpation in both flanks of the abdomen. She was alert and oriented in time, person and space with a Glasgow Coma scale of 15/15. The rest of the exam was normal. Laboratory: Hemoglobin: 14 g/dL; Hematocrit: 41%; WBC: 6,500/μL (Neutrophils: 4,030/μL, Eosinophils: 0/μL, Basophils: 0/μL, Monocytes: 720/μL, Lymphocytes: 1,300/μL); Platelets: 60,000/μL; Glucose: 89 mg/dL; Creatinine: 0.66 mg/dL; Urea: 17 mg/dL; PT: 17.2 sec; PTT: 37.3 sec; INR: 1.33; Albumin: 4.1 g/dL; Sodium: 135 mEq/L; Potassium: 3.55 mEq/L; Chloride: 94 mEq/L; AST: 205 U/L(normal < 40 U/L); GGT: 164 U/L (normal 5-40 U/L); Alkaline phosphatase: 176 U/L; Total bilirubin: 2.1 mg/dL (Direct bilirubin: 0.6 mg/dL), Serologies for HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HTLV I-II were negative. A chest X-ray revealed no abnormal findings (Image A). A non-structural protein 1 (NS1) test for Dengue was negative. A two-band malaria rapid diagnostic test (RDT) which detected P. vivax LDH (Pv-LDH) and P. falciparum histidine rich protein-II (pHRP-II) was performed (Image B). Finally, a thick (Image C) and thin smears (Image D) were performed, revealing the following structures. UPCH Case Editors: Carlos Seas, Course Director / Mario Suito, Associate Coordinator |

|

Discussion: The malaria rapid test was positive for Pv-LDH. Thick and thin smears revealed ringed trophozoites inside enlarged parasitized erythrocytes consistent with P. vivax monoinfection with less than 1% parasitemia. Malaria is a parasitic disease caused by Plasmodium sp. and transmitted by the Anopheles female mosquitoes found in tropical and subtropical regions. It is estimated to be endemic in 84 countries, and the highest transmission rates are seen in sub-Saharan Africa and specific areas of Oceania. African regions report the highest number of cases, accounting for 94% of global infections in 2023 (1). Of the six recognized species known to infect humans commonly, Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax are the most frequent, causing the highest burden of morbidity and mortality, with P. vivax being responsible for over 70% of malaria cases in the Americas (2). Clinical manifestations include a variety of non-specific symptoms, including fever, chills, headache, and vomiting. Severe malaria by P. falciparum manifests with impaired consciousness, severe acute kidney injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome, usually with pulmonary edema, substantial bleeding, shock, acidosis, severe anemia, hyperparasitaemia, and jaundice; the WHO also includes prostration and multiple convulsions as severity criteria (3). Diagnosis is based on microscopy coupled by RDT’s. P. vivax microscopy is characterized by enlarged parasitized RBC’s with ameboid-shaped trophozoites. RDT’s can detect P. vivax through Pv-LDH detection and differentiate it from either P. falciparum or other Plasmodium species, depending on the type of RDT (4). Uncomplicated malaria cases are usually treated with artemisin-based combined therapy (ACT). Artemisins such as arthemeter, artesunate, and dihydroartemisin are rapidly acting antimalarial drugs against all Plasmodium sp. stages, including gametocytes. Artemisinin compounds are coupled (artemisinin combination therapy or ACT) with longer-acting drugs such as lumefantrine, mefloquine, or amodiaquine that clear remaining circulating parasites and protect against the development of resistance. In cases of P. vivax and P. ovale, chloroquine therapy is followed by 14 days of primaquine to target hypnozoites and prevent relapses. If P. vivax malaria is confirmed from a chloroquine-resistant area, an ACT should be used followed by Primaquine (5). References |

|

Gorgas Case 2025-8 |

|

|

The following patient was seen on the inpatient ward of Cayetano Heredia Hospital in Lima by the 2025 Gorgas Course participants.

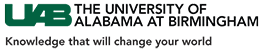

History: A 39-year-old male patient presented with an eight-year history of progressive, disseminated, pruritic cutaneous lesions and a five-day history of diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Eight years before admission, he developed erythematous, painful, and pruritic plaques on the lower extremities and back. Over the following year, the lesions progressed to involve the entire body, including the scalp and face, and were associated with patchy hair loss. He sought care at multiple primary healthcare centers, where topical clobetasol was prescribed with partial improvement. Symptoms persisted and two weeks before admission, he developed fever, chills, and generalized malaise, with worsening of his skin lesions, characterized by increased pain and pruritus (Image A). He was hospitalized at a regional hospital for seven days and discharged with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and oral prednisone (50 mg/24h), with partial improvement and a presumptive diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris. Five days before admission, he developed diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting (4-5 episodes per day), leading to appetite loss and an inability to tolerate solid food. Symptoms persisted, and on the day of admission, he experienced severe generalized weakness, prompting his family to bring him to the emergency room. Epidemiology: The patient is the eldest of nine siblings, all reportedly healthy. His father had a history of similar pruritic skin lesions, though less severe, and died of cirrhosis. His wife has five siblings, all apparently healthy. Socially, he has worked in construction and agriculture in his youth and as a bus driver since the age of 27. He has lived in Ayacucho (until 24 years old), Arequipa (until 36 years old), and then returned to Ayacucho, residing in a two-room adobe house with sewage, water, and electricity, shared with four people. He raises chickens at home. In June 2024, he traveled to Pichari, La Convención (a jungle region). He has no known history of tuberculosis exposure. Physical Examination on admission: On admission, the patient was in poor general condition with vital signs showing tachycardia (HR 118 bpm), normal respiratory rate (RR 16), afebrile (36°C), blood pressure of 118/98 mmHg, and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air (FiO2 0.21). Skin examination revealed warm, dry, disseminated erythematous papules and plaques with moderate scaling and erosions (Image B) and nodular lesions on the scalp (Image C). The patient had mild bilateral lower extremity edema and diffuse lymph node enlargement. Abdominal examination showed epigastric tenderness and dullness over Traube’s space. Neurologically, he was alert and oriented (GCS 15/15) with no meningeal signs or focal deficits. The cardiovascular, respiratory, genitourinary, and musculoskeletal examinations were unremarkable. Laboratory: On admission the patient exhibited a hemoglobin level of 12.3 g/dL, leukocytosis with WBC 10.1 ×10⁹/L, and neutrophil predominance (63.3%, absolute count 6.39 ×10⁹/L). Eosinophilia was noted (13.9%, absolute count 1.4 ×10⁹/L), along with thrombocytosis (561,000/μL, previously 626,000/μL). Biochemistry showed hyponatremia (Na⁺ 123 mmol/L), hypochloremia (Cl⁻ 85 mmol/L), and hypoalbuminemia (2.2 g/dL), with total protein at 4.7 g/dL. Kidney function was stable (creatinine 0.52 mg/dL, urea not reported on DOA). Liver function tests were within normal limits (AST 20 U/L, ALT 13 U/L, total bilirubin 0.6 mg/dL). Coagulation parameters showed PT 13.3 sec, PTT 36 sec, and INR 1.17. Inflammatory markers included an elevated CRP (37 mg/L). Lipase was mildly elevated (104.6 U/L), while amylase (49 U/L) and CPK (23 U/L) were within normal ranges. Serological tests were positive for HTLV-1 and anti-HBc, while HBsAg, HIV and hepatitis C tests were negative. Imaging: Abdominal CT revealed diffuse small and large intestine wall thickening with air-fluid levels with no mechanical obstruction concerning for ileus (Image D). Microbiology: Ova and parasite (O&P) from gastric aspirate, stool and sputum revealed the following structures (Image E). Histopathology: Skin biopsy from the lesions revealed a lymphocytic infiltrate of the dermis invading the epidermis with variable sized lymphocytes with irregular-shaped nuclei (Image F) that stained positive for CD3 and CD4 on immunohistochemistry. UPCH Case Editors: Carlos Seas, Course Director / Mario Suito, Associate Coordinator |

|

Discussion: Skin histopathology revealed findings compatible with ATLL. O&P revealed both filariform and rhabditiform larvae including from the sputum, confirming the diagnosis of hyperinfection syndrome. ATLL is a malignant complication of the often-asymptomatic HTLV-1 infection (1), and its incidence varies according to the endemicity of HTLV-1, the most common places being Southwestern Japan, the Caribbean basin, Western Africa, Iran and Peru (2). It usually develops in chronically infected patients between 60-70 years of age (3) and both treatment and prognosis depend on the clinical subtype of ATLL (4). The most common presentation (60%) with the worst prognosis (8-month median survival) is the acute form typically presenting with fever, weight loss, generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly and lymphocytosis with atypical lymphocytes, some presenting pathognomonic flower-cell appearance. Around 50% of patients also have hypercalcemia. Skin involvement occurs in 25% of patients with tumor-like lesions being the most frequent manifestation (39%), followed by plaques (27%), papules (19%), patches (7%), purpuric lesions (4%) and erythroderma (4%) (5). Prognosis is also influenced by the type of cutaneous lesions, with the nodular/tumoral lesions presenting the worst prognosis (6). Lymphomatous ATLL is the second most common subtype (20%) with similar symptoms but without lymphocytosis. Chronic ATLL occurs in 10% of cases and usually presents with months-to-years of cutaneous lesions, lymphadenopathy and lymphocytosis. Smoldering ATLL is the least frequent subtype (< 10%) with patients usually being asymptomatic with < 5% of circulating neoplastic cells. Diagnosis is made with the identification of characteristic malignant cells on peripheral blood smear, bone marrow or histopathology of cutaneous lesions, and the confirmation of HTLV-1 infection. ATLL malignant lymphocytes are characterized by hyperlobated irregular nuclei with flower-cell appearance with the characteristic CD3+, CD4+, CD25+, CD7-, CD8- immunophenotype. In selected instances HTLV-1 proviral clonality of malignant cells can be demonstrated with PCR based methods (7). Remarkably, Strongyloides stercoralis (Ss) coinfected patients tend to develop ATLL earlier (39 vs 60-70 years of age) (8). The leading hypothesis for this is 1) chronic antigenic stimulation of infected cells leads to accelerated oncogenic mutation accumulation 2) increased proportion of T regulatory lymphocytes caused by Ss downregulates the immune response against malignant lymphocytes and 3) microbial translocation from the GI tract induced chronic inflammation. Ss is geohelminth that shares many of the tropical and subtropical regions were HTLV-1 is endemic, including Peru and affects approx. 50-100 million individuals worldwide (9, 10). Filariform larvae penetrate areas of intact skin, migrate through the circulatory system until reaching the lungs where they access the respiratory tract, climb up until reaching the GI tract where the adult females reside and multiply. Half of those infected remain asymptomatic. The most common symptoms are usually mild gastrointestinal symptoms and eosinophilia. Immunosuppressed patients, particularly those coinfected with HTLV-1 or receiving corticosteroids can develop either strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome with involvement of the GI, respiratory and cutaneous systems or disseminated strongyloidiasis with extra-Loeffler cycle organ involvement (11). The bidirectional relationship between worsening clinical manifestations and outcomes in HTLV-1 and Ss-coinfected patients highlights the neglected nature of these infectious organisms and the need for further research into their combined pathophysiology. Our patient was started on subcutaneous ivermectin, and intravenous antibiotics. The subcutaneous (SC) route for administering ivermectin has been used in patients who cannot tolerate the oral route with mixed results (12). The SC preparation is approved for veterinary use only. Therefore, consent was obtained from the patient. No actual dosing and regimen recommendations exist. He is receiving 200 ugr/kg per day. References |

|

Gorgas Case 2025-7 |

|

|

The following patient was seen on the inpatient ward of Cayetano Heredia Hospital (HCH) in Lima by the 2025 Gorgas Course participants.

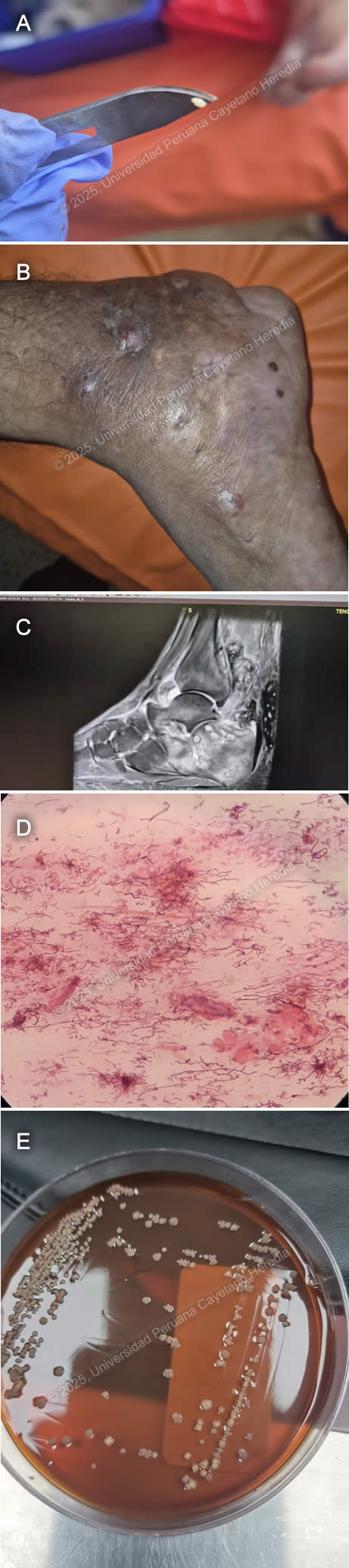

History: A 52-year-old male patient presented to the outpatient clinic in HCH with a seven-year history of swelling, changes in coloration, and discomfort while walking on the right foot. The patient reports that seven years before admission, during a trip to the jungle (Juanjui, San Martin), after playing soccer barefoot, he noticed a small laceration on the sole of his right foot. He did not experience significant discomfort; however, the lesion persisted. Five years before admission, the lesion progressively increased in volume, became edematous, and adopted a tumor-like appearance. Symptoms continued, and two years before admission, he noticed that the tumor-like lesion acquired a dark-brown discoloration and began intermittently discharging white-to-yellowish granules. Epidemiology: He was born in Bagua, Amazonas but moved to Lima 25 years before admission. He previously worked as a rice harvester before coming to Lima and, since moving, has been a handcrafter. Seven years ago, he traveled to Juanjui, San Martín, where he played soccer barefoot. He has not traveled to the jungle ever since. Physical Examination on admission: BP: 120/70 mmHg; RR: 18; HR: 77; T: 26.8°C, Sp02 99% on room air. He was in regular general condition. He presented with a tumor-like lesion on the right foot with grain discharge (Image A), edema with fovea extending from the ankle to the foot (Image B), and a single enlarged right inguinal lymph node measuring 2x1 cm, mobile, and non-tender to palpation. His respiratory and abdominal examinations were non-contributory. The musculoskeletal evaluation showed muscle contraction on the inner part of the thigh with preserved strength in the right lower limb. Neurologically, he was alert with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15/15, without focal or meningeal signs. The rest of the exam was normal. Laboratory: Hb 10.7 g/dL, MCV 88.2 fL, MCH 28.4 pg, WBC 7.46 ×10³/µL (Neut 5.33 ×10³/µL, Lymph 1.4 ×10³/µL, Mono 0.46 ×10³/µL, Eos 0.20 ×10³/µL, Baso 0.07 ×10³/µL), Plt 506 ×10³/µL, Glu 93 mg/dL, Urea 35 mg/dL, Cr 0.84 mg/dL, AST 17 U/L, ALT 13 U/L, T. Bili 0.41 mg/dL (D. Bili 0.16 mg/dL, I. Bili 0.25 mg/dL). Serology tests for HIV, HTLV, HBsAg, and RPR were negative. Imaging: A foot MRI revealed lytic lesions in the tarsus and metatarsus and a soft tissue abscess in the Achilles heel and foot sole (Image C). Microbiology: Gram stain from the grains revealed the following structures (Image D) and culture revealed the following colonies (Image E). UPCH Case Editors: Carlos Seas, Course Director / Mario Suito, Associate Coordinator |

|

Discussion: Gram stain from the grains revealed gram-positive 0.5-1-μm-wide filamentous structures compatible with an agent of actinomycetoma, later identified through MALDI-TOF as Nocardia farcinica. Mycetoma (also known as Madura foot) is the most common worldwide subcutaneous tropical infection first described in 1842 in Madras, India. The latest reports indicate over 8,700 cases globally, with approximately 127 new cases per year across 23 countries, the most affected being India, Sudan, and Mexico (1). Males are disproportionately affected (6:1), and the disease primarily occurs in adolescents and young adults under 40 (2). Actinomycetoma, which predominates in the Americas, is caused by various species of aerobic filamentous bacteria, including Nocardia, Actinomadura, and Streptomyces. Eumycetoma, by contrast, is a fungal infection most commonly caused by Madurella mycetomatis and is more prevalent in Africa and Asia (3).Clinically, mycetoma is characterized by tumor-like swellings, sinus tracts, and grain discharge. The lower extremities are affected in 80% of cases. While the disease is usually localized, actinomycetomas more frequently extend deeper into bones and joints than eumycetomas. Actinomycetoma grains tend to be smaller than those of eumycetomas, are composed of filamentous bacteria, and function as biofilms, limiting antibiotic penetration. Actinomycetoma grains are typically white or pale yellow, except for those caused by Actinomadura pelletieri, which appear red to pink. Eumycetoma grains, on the other hand, are usually black, brown, yellow, or white, depending on the causative fungal species. In this case, the presence of white granules ruled out Madurella mycetomatis, which typically produces black granules (4). Diagnosis is primarily clinical, based on the triad of swelling, sinus tracts, and grain drainage. Imaging assesses disease extent, while culture and molecular methods confirm the causative organism (5). Grains, either spontaneously extruded or aspirated, can be cultured on blood or Sabouraud agar, and drug susceptibility testing is recommended for all cases (6, 7). Among Nocardia species, the most common causative agent is Nocardia brasiliensis. A recent study from China found Nocardia farcinica the most common species among all nocardiosis cases and was, as most Nocardia species, susceptible to TMP-SMX, Amikacin, and Linezolid (8). Combination antibiotic therapy is recommended to prevent antimicrobial resistance. Treatment typically involves a trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) backbone combined with an aminoglycoside, rifampin, or dapsone for 6–24 months. While surgery is commonly used for eumycetomas, it is less frequently required for actinomycetoma due to the high effectiveness of medical therapy (3, 9). Our patient was started on a combination regimen of TMP-SMX and amikacin. References |

|

Gorgas Case 2025-6 |

|

|

The following patient was seen in Cuzco by the 2025 Gorgas Course participants.

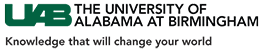

History: A 43-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department at Cuzco with a 6-month history of productive cough, fever and 3 months of disseminated cutaneous lesions. Six months before admission the patient presented productive cough with blood-tinged sputum, subjective fevers and night sweats. Symptoms persisted and 3 months before admission multiple umbilicated papules first appeared in the palms and soles and progressed to affect the rest of the body. Lesions were painful, non-pruriginous and had no discharge. Three days before admission he developed shortness of breath for which he attended the ED and was admitted. Epidemiology: The patient was born in the city of Cuzco and worked as an agricultural technician. He lived with his female partner, denied polygamy, MSM or contact with sexual workers. He traveled to the low jungle in two occasions, 1 year and 7 months, before admission where he had significant exposure to animals including birds and bird guano. Physical Examination on admission: BP: 120/70 mmHg; RR 26; HR 91; T: 36.5°C, Sp02 92% on room air. He appeared to be tachypneic and in mild respiratory distress. On the skin, multiple erythematous umbilicated papular lesions on the palms, soles, upper and lower extremities, trunk, face and tongue were noted (Image A). There was no palpable lymphadenopathy. There were decreased breath sounds bilaterally with bibasilar crackles. The rest of the exam was normal. Laboratory: WBC 12,910/µL with Seg 10,700 (82.9%), Lin 1,110 (8.6%), Mon 750 (5.8%), Bands 0.9%; Hb 12.6 g/dL with MCV 76.1 fL, MCH 25.7 pg; Platelets 332,000/µL, CRP: 19.44 mg/L. Creatinine 0.91 mg/dL, Urea 40.9 mg/dL, AST 34 U/L, ALT 73 U/L, TB 7.2 mg/dL (DB 1.79 mg/dL), Alk. Phos 298 U/L, GGT 335 U/L. Na+ 139 mmol/L, K+ 5.4 mmol/L. TSH 1.91 µIU/mL, free T4 1.45 ng/dL, T3 0.26 ng/mL. HIV, HTLV-1, VDRL, HBsAg, anti-HBc, HCV, HAV were negative. Anti-MPO (ANCA P), Anti-PR3 (ANCA C) negative. Blood cultures came back negative, as well as AFB sputum, urine, and stool. Sputum GeneXpert was negative, but a BAL sample GeneXpert was positive for MTB with indeterminate rRifampicin resistance. Imaging: A CT chest revealed alveolar consolidation in the right lower lobe with peripheral air bronchogram along withnd other scattered ground-glass opacities in both lungs and in the left lower lobe, cavitary-appearing lesions with peripheral alveolar consolidation (Image B). Both head and Abdominopelvic CT were normal. Pathology: : A skin biopsy (Image C, H&E stain) and culture (Image D) from the lesions were performed, revealing the following structures. UPCH Case Editors: Carlos Seas, Course Director / Mario Suito, Associate Coordinator |

|

Discussion: Histopathology revealed budding yeasts and culture demonstrated fungal colonies compatible with Cryptococcus sp. Cryptococcosis is caused by the ubiquitous yeasts of Cryptococcus neoformans, C. gattii, and, less commonly, C. laurentii and C. albidus. C. neoformans is most commonly isolated from soil contaminated with bird (pigeons, turkeys and chickens) guano. Humans are infected after inhalation of the Cryptococcus sp. Propagule, which in normal hosts is eliminated, but in certain cases and more frequently in immunosuppressed patients, can proliferate and cause invasive disease. Of all affected patients, 80-85% have a predisposing condition, the most common being HIV infection (1). Although less frequently affected, the remaining 20-25% of non-HIV and non-transplant (NHNT) patients have more lung involvement, higher mortality (2), and longer duration of symptoms (34 days vs 81 days, p < 0.001) (3). Pulmonary involvement is the second most common location after CNS and includes well-defined single or multiple parenchymal nodules, masses, parenchymal infiltrates, hilar lymphadenopathy, pleural effusions, and cavitary lesions (4). Cutaneous cryptococcosis almost exclusively represents disseminated disease and is the third most affected organ with protean manifestations. Papules with an ulcerated center are the most common manifestation and may resemble the umbilicated papules of molluscum contagiosum (5). Diagnosis involves either direct observation of the encapsulated yeasts, culture and antigen detection. Classically, the use of the inverse contrast staining of India ink has been used with high specificity (100%) low sensitivity in non-HIV (50%) compared to moderate to high (80%) in HIV infected patients (4). Yeasts surrounded by apparently empty spaces may be seen in H&E stains from affected tissues. The polysaccharide capsule can by identified with mucicarmine and alcian blue stains and the yeasts as well as the narrow budding can be identified using silver fungal stains such as Gomori methenamine stain. Culture from CSF and peripheral blood can give positive results in 3-7 days and the quantitative analysis of the colony count can be used to evaluate antifungal therapy effectiveness. Glucuronoxylomannan (GXM) polysaccharide antigen detection using the latex agglutination test is highly sensitive and specific when used in serum and CSF. Recently, a cheap, rapid, and simple lateral flow assay (LFA) has been developed with comparable test characteristics, widely replacing latex agglutination in routine clinical practice (6-9). Antigen titer measurement is inaccurate and should not be used for treatment decisions. Treatment of non-CNS cryptococcosis is extrapolated from CNS data. Induction therapy with liposomal amphotericin B (3-4 mg/kg IV) daily plus flucytosine (100 mg/kg PO daily in four doses) should be continued for at least 2 weeks. Before switching to consolidation therapy, the patient should have clinical improvement and CSF sterilization, the latter being demonstrated by a repeat LP for fungal culture at the 2-week mark before switching to Fluconazole 400-800 mg PO daily consolidation therapy for at least 8 weeks, after which patients can be switched to maintenance therapy with Fluconazole 200mg PO daily for at least 1 year (10, 11). In cases of CNS Cryptococcosis, management of increased intracranial pressure with either repeat LP’s or lumbar drain decreases mortality and should be pursued aggressively (12). Our patient was started on both antifungal and drug-sensitive tuberculosis treatment. GeneXpert Ultra detects M. tuberculosis (LOD: 16 CFU/mL) and rifampicin resistance (LOD: ~100 CFU/mL) via rpoB mutations. In trace-level paucibacillary TB, resistance cannot be determined, requiring confirmation with MGIT culture or Line Probe Assays (13). References |

|

Gorgas Case 2025-5 |

|

|

The following patient was seen in Cuzco by the 2025 Gorgas Course participants.

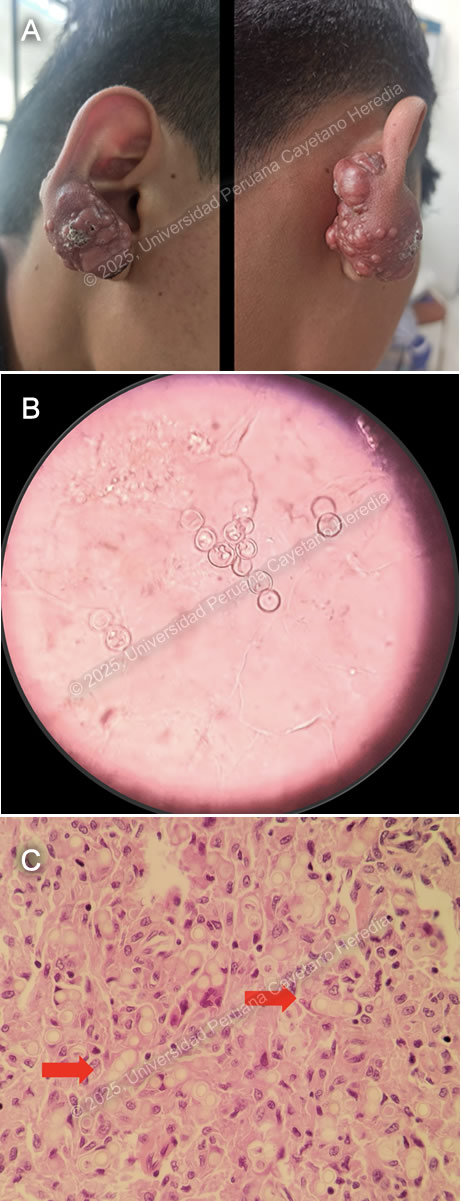

History: A 17-year-old male patient with a history of epilepsy presented to the outpatient clinic in Cuzco with a 10-year history of a progressive lesion on his right earlobe. Ten years before admission, he noticed a non-painful, non-pruritic, papule-like lesion on his right earlobe. The lesion increased significantly in size, prompting surgical removal seven years before admission. Unfortunately, the lesion recurred after surgery with a faster growth rate, developing a tumor-like, verrucous appearance, associated with burning pain and pruritus.. The lesion was non-anesthetic, had no drainage or fistulation, and was not associated with systemic symptoms or evidence of metastatic disease. Epidemiology: The patient was born and raised in Cuzco, a highland city in Peru. Fourteen years before admission, he traveled with his father to Madre de Dios in the low jungle of Peru, where he stayed for two years. He returned to Madre de Dios for two weeks one year before admission. He also reported contact with a cousin who had tuberculous meningitis. Physical Examination on admission: BP 100/60 mmHg, RR 18 breaths per minute, HR 71 bpm, Temp 36.4°C, SpO₂ 92% on room air. A tumor-like exophytic lesion with multiple nodules and superficial crusting was noted on the helix and lobule of the right earlobe (Image A). The lesion was firm and hard to touch, with no discharge, regional lymphadenopathy, or sinus tracts. The rest of the physical exam was within normal limits. Laboratory: Hb: 18.7 g/dL (Hematocrit: 54%); Leukocytes: 10,260/µL (Neutrophils: 7,120/µL, Eosinophils: 120/µL, Lymphocytes: 2,370/µL); Platelets: 397,000/µL; Glucose: 97 mg/dL; Urea/Creatinine: 30/1.16 mg/dL; AST/ALT: 27/37 U/L; Alkaline Phosphatase: 119 U/L; Albumin: 4.5 g/dL; Sputum AFB x2: Negative. HIV, HTLV-1, Syphilis, HBsAg, Anti-HBc, and HCV non-reactive. UPCH Case Editors: Carlos Seas, Course Director / Mario Suito, Associate Coordinator |

|

Discussion: Both KOH-stained light microscopy and histopathology revealed fungal structures compatible with Paracoccidioides loboi. Lobomycosis is an exceedingly rare subcutaneous mycosis caused by the yet unculturable and recently renamed Paracoccidioides loboi (formerly Lacazia loboi). Accidental trauma, particularly involving plants and thorns, is thought to be the primary transmission mode, although not in all cases (1). The latest prevalence estimates report 907 total cases of lobomycosis, with 55% of cases originating in Acre State, Brazil (2). The remaining cases come from the Amazonian rainforest regions of Brazil, Peru, and Colombia. Cases in developed countries such as the United States have been reported in migrants or tourists returning from endemic areas (3). Notably, bottlenose dolphins have also been found to be affected by this disease. Lobomycosis remains restricted to the skin and typically follows a decades-long progression. The classical lesions are red, hard, shiny keloidal plaques or nodules that may ulcerate with secondary crusting or develop a verrucous appearance over time. Local extension is the norm, and there have been no reported cases of metastatic disease. The most common sites of involvement are the lower extremities, followed by the ears, upper extremities, and head. Disseminated cases have been described, presenting with multifocal lesions, intense pruritus, and marked ulceration. The diagnosis is confirmed by direct visualization of fungal cells in KOH-stained light microscopy or histopathological analysis of clinical specimens, revealing round 9-µm single or short-chain yeast cells with thick double cell walls. Specimens for light microscopy can be obtained using the “Scotch tape test,” where vinyl adhesive tape is applied to the crusted lesion and transferred to a glass slide for KOH staining. Histopathology (Hematoxylin-eosin or Grocott-Gomori staining) is the gold standard diagnostic test (3). Since P. loboi has not been successfully cultured, 18S ribosomal analysis has revealed its close relation to Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (4) The main differential diagnosis includes bacterial infections such as cutaneous TB (Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis), non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infections, actinomycetoma, and botryomycosis; fungal infections such as paracoccidioidomycosis, eumycetoma, sporotrichosis, and chromoblastomycosis; and parasitic infections such as cutaneous leishmaniasis (5) There is no curative treatment for lobomycosis. Surgery is an option, though primarily for cosmetic purposes. Case reports have described successful treatment with posaconazole, clofazimine, and itraconazole (6-8). Our patient was treated with 1 month of TMP/SMX and itraconazole, but no significant clinical response was observed, leading to surgical removal of the lesion. References |

|

Gorgas Case 2025-4 |

|

|

The following patient was seen in the inpatient ward of Cayetano Heredia Hospital in Lima by the 2025 Gorgas Course participants.

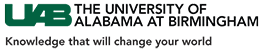

History: A 43-year-old male patient with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department of Cayetano Heredia Hospital (HCH) with 2.5 months of diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Two months and fifteen days before admission, he presented with watery diarrhea without mucus or blood, 3-4 times every other day, associated with postprandial abdominal pain. Two months before admission, he attended a Primary Care Center, where he tested positive for HIV and was promptly started on ART (tenofovir, lamivudine, dolutegravir). His symptoms remained stable with marginal improvement, and one month before admission, he developed marked abdominal distention associated with postprandial vomiting. This was aggravated by the appearance of lower extremity edema. On the day of admission, he presented with worsening abdominal pain. An ambulatory colonoscopy revealed multiple ulcers in the descending, sigmoid, and ascending colon and cecum, including fistulizing ulcers in the descending and sigmoid colon. Of note, he had a 15 kg involuntary weight loss in the last 6 months and 2.5 months of asthenia. He denied headaches, visual symptoms, fever, dyspnea, cough, or chest pain. Epidemiology: The patient was born in Cerro de Pasco, a city located in the central highlands of Peru, but currently lives in northern Lima, where he moved 25 years ago after working for one year as a coffee farmer in the jungle of Chanchamayo. He denies any known TB contacts and has no pets. He has had five male sexual partners with inconsistent condom use and was previously treated for genital herpes one year ago. Physical Examination on admission: BP: 110/70 mmHg, RR: 18, HR: 115, Temp: 36.1°C, SpO₂: 96% on room air. He appeared malnourished but was ventilating spontaneously and in no acute distress. An approximately 2 × 2 cm ulcer in the right upper hard palate and 2-4 smaller ulcers in the left internal cheek were found (Image A). Pitting edema up to his knees was noted, and had multiple palpable 0.5 × 0.5 cm mobile, non-tender cervical lymph nodes. He had normal breath sounds with diffuse wheezing but no rales or crackles. His abdomen was markedly distended, with increased bowel sounds and shifting dullness. The rest of the exam was normal. Laboratory: Hemoglobin 9.9 g/dL (MCV 79.6 fL, MCHC 35.6 g/dL), WBC 8,300/uL (0% bands, 77.2% neutrophils, 0.1% eosinophils, 0.1% basophils, 8.6% monocytes, and 14% lymphocytes), platelets 380,000/uL. Urea 31 mg/dL, creatinine 0.64 mg/dL. AST 31 U/L, ALT 28 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 108 U/L, total bilirubin 0.5 g/dL, LDH 211 U/L. INR 1.23. A repeat HIV test was positive, and RPR, hepatitis B, and C serologies were negative. An initial HTLV-1 ELISA test at a reference lab was positive, but an in-house repeat ELISA was negative, confirmatory Western Blot is pending. A thorough TB workup was negative, including sputum AFB and GeneXpert ultra, urinary TB LAM, and tuberculin skin test. The serum cryptococcal lateral flow assay was negative, as were serial stool O&P’s. Lastly, a urinary Histoplasma sp. antigen was found to be positive. Imaging: An abdominal ultrasound revealed an estimated 1-1.5 L free intraperitoneal fluid collection and hepatomegaly. An abdominal X-ray showed dilated small and large bowel loops and multiple air-fluid levels (Image B). An abdominal CT scan showed dilated intestinal loops associated with bowel wall edema. A chest CT showed multiple bilateral nodules associated with areas of ground-glass opacities and multiple thin-walled cavitary lesions (Image C). A KOH stain from a BAL sample was performed (Image D). Results from biopsies obtained from the colonoscopy are shown (Image E, H&E stain; Image F, Grocott stain). UPCH Case Editors: Carlos Seas, Course Director / Mario Suito, Associate Coordinator |

|

Discussion: Both the direct BAL smear and the large intestine biopsies revealed variable-sized yeasts with narrow-based budding and birefringent walls, findings compatible with Paracoccidioides sp. infection. PCM is an endemic mycosis of Latin America’s rainforests caused by the thermally dimorphic fungus Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and, less commonly, by Paracoccidioides lutzii (1). Brazil reports 80% of all cases, with the remainder being from Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, Mexico, and Peru (2). Transmission occurs through the respiratory route, with an estimated 10 million people infected in Latin America, most of them being over 30 years old, with no racial predominance but with a male-to-female ratio of around 14:1 (3). The most associated risk factor is working as a farmer in coffee or tobacco crops (4). PCM can be clinically divided into asymptomatic infection, active disease, and sequelae or residual form. Active PCM disease can be further classified into an acute/subacute or juvenile form, a chronic progressive or adult form that can be unifocal or multifocal, or a mixed form with characteristics of both the juvenile and chronic progressive forms. The juvenile form develops in days to weeks and commonly presents with fever and reticuloendothelial system involvement (generalized lymphadenopathy, liver and spleen enlargement). At-risk populations are those less than 30 years old and immunosuppressed patients, such as those with advanced HIV (5). The chronic progressive form develops over months to years and commonly presents with bilateral, apical-sparing pulmonary involvement, localized lymphadenopathy, and oral mucosal lesions. Pulmonary symptoms are usually mild, with hemoptysis being rare. Radiological findings can include alveolar, interstitial, and/or nodular patterns. Cavitary lesions and pleural effusions are less common. Pulmonary fibrosis is the eventual common endpoint for severe and/or untreated PCM pulmonary disease (6). Mucosal lesions are more common in the chronic form and usually involve the oral mucosa. Lesions tend to be painful, destructive, and ulcerative, accompanied by gingival infiltration causing tooth loss. Skin lesions are more common in the juvenile form, are pleomorphic, and frequently affect the face. Intestinal involvement can affect any segment of the GI tract but most commonly affects the ascending colon, cecum, and ileum, followed by the small intestine. Symptoms include abdominal pain, weight loss, and chronic diarrhea (7). Patients with advanced HIV and CD4 counts less than 200 are at risk for the reactivation of latent foci. These patients tend to present with disseminated, multi-organ involvement, exhibiting characteristics of both the chronic multifocal and juvenile forms (8). Of note, HTLV-1 coinfected patients have also been described with a predominance of juvenile and/or mixed forms and intestinal involvement (9). The fastest, most cost-effective, and clinically applicable diagnostic method is the direct examination of round yeast cells with peripheral budding in KOH-prepared samples from affected tissues, such as oral or skin lesions, sputum, lymph node aspirates, and CSF (10). The same yeast cells can be seen in histopathological samples, which can be enhanced by silver stains, PAS, and/or immunofluorescence techniques. Culture is the second standard diagnostic method but requires cool temperatures of 18-24°C and takes up to 20-30 days to grow. Serological tests remain an area of ongoing research, being utilized in endemic countries like Brazil but unavailable in most settings. Antibody detection using the double immunodiffusion method (DID) with the 43 kDa antigen is the most used method but remains positive years after exposure, limiting its use in detecting active disease (11). For mild to moderate cases of PCM, the preferred treatment option is itraconazole, with a variable duration of treatment from 9 to 18 months. Cotrimoxazole can also be used for 18 to 24 months. In cases of severe and disseminated presentation, the preferred therapeutic choice is 2 to 4 weeks of Amphotericin B until clinical stabilization, followed by a switch to oral maintenance therapy (11). Our patient was started on amphotericin B 1.0 mg/kg. References |

|

Gorgas Case 2025-3 |

|

|

The following patient was seen in the inpatient ward of Cayetano Heredia Hospital (HCH) in Lima by the 2025 Gorgas Course participants.

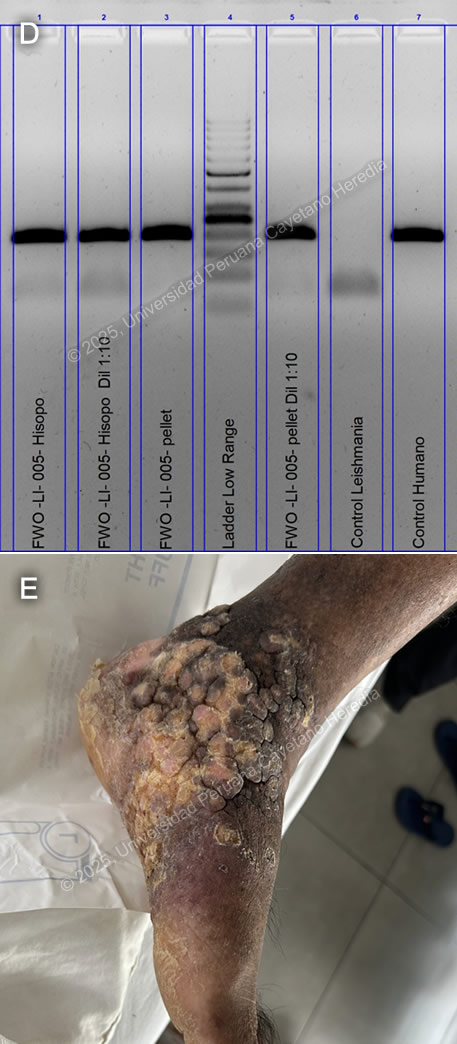

History: A 70-year-old male patient with no significant past medical history presented to the outpatient clinic at HCH with a six-year history of expanding, painless skin lesions on his left foot. Six years before admission, he developed a painless, non-pruritic, 1 x 1.5 cm non-healing papule that became ulcerated on the dorsum of his left foot. At that time, he sought care at a local health center, where he received three intralesional pentavalent antimonial injections over three consecutive days, with partial clinical improvement. Five years before admission, the lesion increased in size to 5 x 5 cm and was accompanied by localized swelling. The lesion continued to expand, and four months before admission, it became moderately painful, impairing his daily activities. Due to persistent symptoms, he attended the dermatology clinic and was admitted for further workup and management. Epidemiology: The patient was born and resides in La Merced, a city located in the high jungle of Peru, where he works in agriculture cultivating coffee and fruits. He frequently walks barefoot in the jungle soil and experiences numerous mosquito bites. He denies any travel outside his place of birth. He has no known tuberculosis (TB) contacts but reports that multiple neighbors throughout his lifetime have presented with similar non-healing cutaneous ulcers. Physical Examination on admission: BP: 110/80 mmHg, HR: 70 bpm, RR: 20 breaths per minute, T: 36.5°C, SpO2: 98% on room air. The skin examination revealed multiple tumor-like, verrucous, confluent hyperkeratotic plaques with irregular and poorly defined borders in the middle and lateral malleolar regions and on the heel of the left foot, with hyperpigmentation and scaling (Image A). The rest of the examination was normal. Laboratory: Hemoglobin: 9.4 g/dL (MCV 92 fL, MCHC 33 g/dL), Hematocrit: 29%, WBC: 4,400/µL (0% bands, 65.1% neutrophils, 8.7% eosinophils, 0.5% basophils, 11.3% monocytes, 14.4% lymphocytes), Platelets: 433,000/µL, Creatinine: 0.81 mg/dL, Sodium: 140 mEq/L, Potassium: 4.9 mEq/L, Chloride: 104 mEq/L. Serology for HIV, HTLV-1, RPR, and Hepatitis B and C were all negative. A foot X-ray showed no bone involvement (Image B). A Giemsa-stained scraping from the border of a lesion was performed (Image C; reference image, original of low quality). UPCH Case Editors: Carlos Seas, Course Director / Mario Suito, Associate Coordinator |

|

Discussion: GeneXpert ultra and acid-fast bacilli (AFB) staining from the tissue biopsy were negative, as was the TB liquid media (MGIT) culture. KOH and fungal cultures were also negative. The Montenegro intradermal hypersensitivity test was positive (30 x 35 mm). A skin punch biopsy revealed parakeratosis and acanthosis associated with a lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate and epithelioid granulomas; however, no definitive amastigotes were seen. A kinetoplast DNA PCR (kDNA PCR) for Leishmania sp. was positive, confirming the diagnosis (Image D). Finally, the patient presented a remarkably positive therapeutic response after treatment with Amphotericin B, showing marked improvement of the lesion (Image E). Leishmaniasis is endemic in 88 countries, including Brazil, French Guiana, Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Peru (1). The most common manifestation is cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), which affects 10 million people worldwide. Affected patients typically live in or have a history of travel to endemic areas. In Peru, over 7,000 cases are reported annually (2,3). CL in Peru is a zoonosis caused by Leishmania species, almost exclusively from the subgenus Viannia, particularly L. peruviana, L. braziliensis, L. guyanensis, and L. panamensis. Humans become infected when the sandfly vector (Lutzomyia sp.) inoculates promastigotes into the host’s bloodstream while taking a blood meal. These promastigotes are phagocytized by macrophages, where they develop into amastigotes that multiply until they are released and infect other cells. CL usually develops 2-8 weeks after inoculation. The most common presentations include the localized-ulcerative form, the nodular or sporotrichoid form, and the diffuse and disseminated cutaneous forms. Less common manifestations include plaque, psoriasiform, and verrucous leishmaniasis, which represent 2-5% of all CL cases (4). Verrucous leishmaniasis is a rare subtype of the already infrequent atypical cutaneous leishmaniasis subgroup. It is classically described as hyperkeratotic plaques covered by thick, adherent crusts. Diagnosis relies on identifying high-risk patients based on compatible clinical manifestations and the appropriate epidemiological exposure, followed by specific parasitological diagnostic tests. Most confirmatory tests require invasive tissue biopsies, where 1) direct microscopy with commonly used Giemsa stain reveals amastigotes, 2) culture from the lesion demonstrates promastigotes, and/or 3) PCR amplification detects genomic DNA from Leishmania sp. Serology has no role in the diagnosis of leishmaniasis. A positive Montenegro skin test demonstrates a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to Leishmania antigens but cannot differentiate between previous exposure and active disease. Speciation impacts treatment decisions regarding initiation, regimen selection, duration, and dosage. It can be performed using isoenzyme analysis requiring cultured promastigotes or molecular methods like PCR from a tissue sample (5). New World cutaneous leishmaniasis may be treated topically with paromomycin and gentamycin, intralesional injections of pentavalent antimonials, or physical methods such as thermal and cryotherapy (6). For patients with extensive (>5 cm) or multiple (≥ 5) lesions, immunosuppression, or species associated with mucosal disease (L. braziliensis, L. guyanensis), systemic treatment is recommended. Systemic options include intravenous pentavalent antimonials (SbV) (sodium stibogluconate, meglumine antimoniate) and Amphotericin B, as well as oral Miltefosine (7). Although no controlled randomized trials have demonstrated a significant statistical difference between amphotericin B and SbV, extensive cutaneous disease, such as in this case, is typically treated with Amphotericin B (8). References |

|

Gorgas Case 2025-2 |

|

|

The following patient was seen in the inpatient ward of the Cayetano Heredia Hospital (HCH) in Lima by the 2025 Gorgas Course participants.

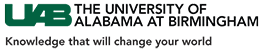

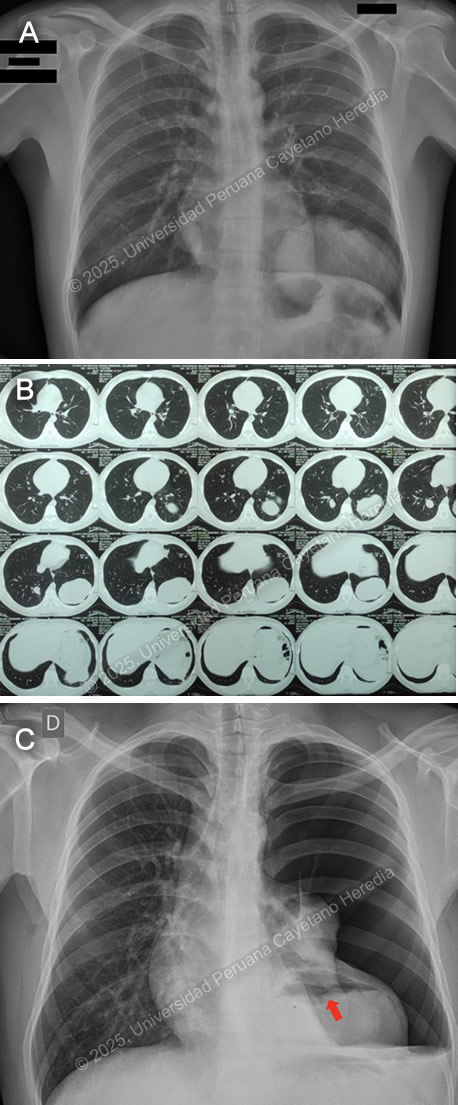

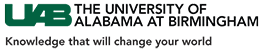

History: A 21-year-old male patient with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department of HCH with a 5-month history of cough and chest pain. Five months before admission, he presented sporadic dry cough and occasional mild left pleuritic chest pain. He attended an occupational medicine consult where a routine chest X-ray was performed, revealing a radiopaque circular lesion in the left hemithorax (Image A), and a follow-up chest CT confirmed the presence of a 72x98x68mm left-sided pulmonary lesion and an additional right-sided 19x18x23mm hyperdense pulmonary lesion (Image B). Three weeks before admission his cough became productive with whitish sputum and was associated with shortness of breath on exertion. Ten days before admission, the pleuritic pain intensified and disrupted his sleep. Five days before admission, he presented a cough with blood-tinged sputum, generalized malaise, and subjective fever. Due to the persistence of symptoms, he traveled to Lima and attended the ED. Epidemiology: The patient was born and lives in Oyon, a city in northern Lima province at an altitude of 3600 meters above sea level. He lives in a rural area where he works as a mechanic and on his family’s farm, feeding, cleaning, and caring for sheep, cows, cats, and dogs. The dogs live inside the house and are fed on the dead sheep’s viscera. He has only traveled to rural areas nearby. He has no known TB contacts and no other family members have presented similar symptoms. Physical Examination on admission: BP was 100/60 mmHg, RR 28, HR 92, afebrile at 37°C with a Sp02 of 90% on room air. Breath sounds were abolished in the left hemithorax, and there was hyper resonance to percussion in the upper 2/3 and dullness in the lower 1/3 on the left hemithorax. The rest of the exam was normal. Laboratory: Hemoglobin was 17 g/dL (13-16 g/dL), WBC 17 100/uL (4-12 x 10^3/uL) with no bands, 51.6% neutrophils, 15.9% lymphocytes, 27% eosinophils (absolute count: 4 595, normal being less than 500/uL), 0% basophils, 4.9% monocytes. Platelets 391 000/uL. Urea 29 mg/dL, Creatinine 0.83 mg/dL, Sodium 142 mEq/L (135-145 mEq/L), Potassium 4.35 mEq/L (3.5-5.5 mEq/L), Chloride 107 mEq/L (96-106 mEq/L). Total bilirubin 0.53 g/dL with a direct of 0.32 g/dL. AST 14, ALT 24 IU/L (normal less than 40 IU/L). CRP 4.6 mg/dL (normal less than 0.3 mg/dL). PT 13.5 sec, PTT 29 sec with an INR of 1.15. HIV test was negative and VDRL was non-reactive. Imaging: A chest X-ray was performed on admission (Image C) followed by a normal abdominal ultrasound. UPCH Case Editors: Carlos Seas, Course Director / Mario Suito, Associate Coordinator |

|

Discussion: The chest X-ray on admission revealed a left side hydropneumothorax with a ruptured cyst on the left lung base showing the “water lily” sign (Image C, red arrow), which was more evident on chest imaging after chest tube insertion (Image D). Western Blot for Echinococcus granulosus was positive for the 21kDa, 16kDa, and 8kDa antigens, confirming the diagnosis. PHD is the second most common manifestation of cystic echinococcosis (CE) representing 20-30% of all cases (1). CE has an annual incidence in endemic areas of 1 to 200 per 100,000 and a mortality rate of 2-4% (2), affecting countries from South America, Eastern Africa, Central Asia, and the Mediterranean (1). It is commonly found in impoverished rural areas. Most affected individuals have one or more risk factors, including living in unsanitary conditions, raising livestock such as sheep, herding or guarding dogs often near homes that are fed offal, and slaughtering livestock close to humans and dogs (3). Echinococcus granulosus eggs are released by the adult tapeworms residing in the definitive hosts (canids, mainly dogs) GI tract that are ingested by humans who act as accidental hosts. Eggs hatch in the intestine, releasing oncospheres that enter the portal circulation or lymphatic system, reaching the liver, where they develop into hydatid cysts (metacestode larvae). The hydatid cyst is composed of an acellular laminar layer and an internal germinal layer that produces a clear hydatid fluid, protoscoleces, and daughter cysts, and is surrounded by a third membrane, the adventitial layer (pericyst), formed by the host immune reaction to the cyst and fibrous tissue. Oncospheres are usually trapped in the hepatic parenchyma, but some may travel through the liver sinusoids and pass through the hepatic veins and inferior vena cava, reaching the right heart and landing in the lungs or pass the lungs and through the left side of the heart reach other organs. PHD has a variable clinical presentation depending on location, size, and cyst wall integrity. It can be discovered incidentally since it can be asymptomatic until rupture, fistula development, mass effect, or other complications occur (4). Some symptoms and signs associated with cysts include shortness of breath, coughing, hemoptysis, pneumonia, atelectasis, and the expectoration of a salty fluid (‘’vomica’’) when a cystobronchial fistula is formed (5). Diagnosis is based on radiological findings and complementary confirmatory serology. Serology includes sensitive screening tests like enzyme immunoassays (EIA) and specific confirmatory tests like immunoblot (Western blot). Screening tests have a sensitivity of 80-100% for liver cysts but only 50-56% for lung cysts. Therefore, a high false-negative incidence rate must be considered, particularly for cyst stages where the host has not been exposed to the parasitic antigen (CE1) or for biologically inactive cysts (CE4, CE5) (6). Surgery is the cornerstone of therapy for PHD. It should be pursued first in the co-existence of pulmonary and liver cysts because of the higher risk of rupture and cystobronchial fistulas of the former (5). Treatment with albendazole 10-15 mg/kg divided into two doses can be started 1-3 days before surgery and continued 3 months postoperatively. In cases where the cyst contents spill into the pleural space either spontaneously or iatrogenically, as in our patient’s case, it is essential to begin antiparasitic treatment promptly alongside surgical intervention and thorough irrigation of the pleural space with isotonic saline to prevent secondary CE (5). Primary antiparasitic treatment without surgical involvement is usually avoided because of the risk of treatment-induced cyst membrane detachment, rupture, and opening of cystobronchial fistulas, except for small lung cysts less than 5 cm (7). References |

|

Gorgas Case 2025-1 |

|

|

The Gorgas Courses in Clinical Tropical Medicine are given at the Tropical Medicine Institute at Cayetano Heredia University in Lima, Perú. For the 29th consecutive year, we are pleased to share interesting cases seen by the participants that week during the February/March course offerings. Presently, the 9-week Gorgas Course in Clinical Tropical Medicine is in session. New cases will be emailed every Tuesday/Wednesday for 9 weeks. Each case includes a brief history and digital images pertinent to the case. A diagnosis and a short discussion follows.

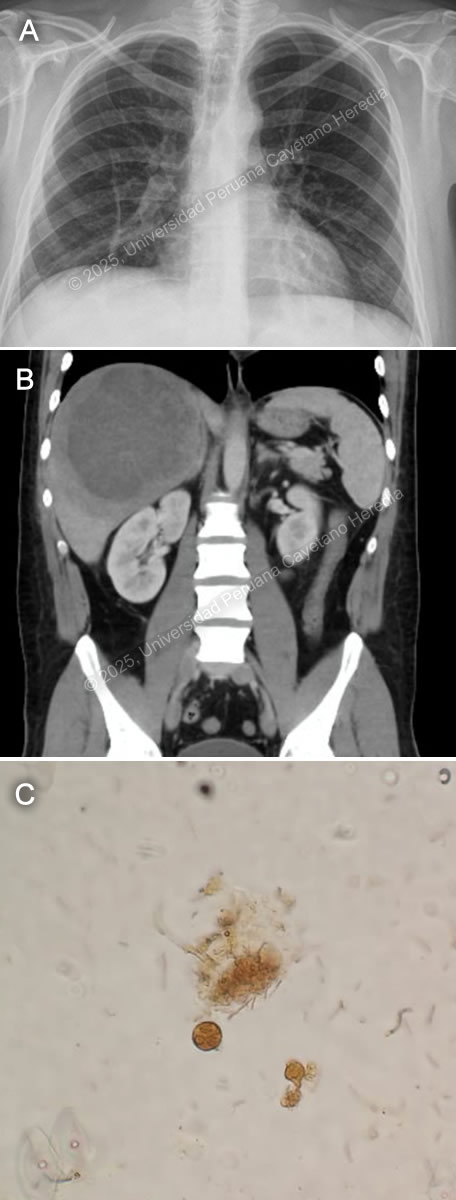

History: A 34-year-old male patient with no significant PMH presented to the ED with a 2-week history of abdominal pain and subjective fevers. Two weeks before admission, he presented epigastric pain associated with nausea, decreased appetite, and fever quantified at 39 C. One week before admission, right pleuritic chest pain was added. Symptoms persisted, and on the day of admission, an abdominal US revealed hepatomegaly with a 13.4 x 3.6cm heterogeneous liver lesion. Epidemiology: The patient was born in Lima, Peru's capital, but currently lives in the city of Tumbes, in the northern part of the country’s coastline. He works as an independent vendor in the textile industry and constantly travels from Lima to Tumbes. While in Tumbes, he endorses eating raw vegetables, abundant seafood, including blood clam ceviche, from street vendors and drinking non-potable water. Two weeks before the onset of symptoms, he reported two weeks of self-limited watery diarrhea. Physical Examination on admission: BP: 120/80 mmHg; RR: 18; HR: 88; T: 38.4 °C, Sp02 97% on room air. The patient didn't appear to be in any acute distress. There was no skin rash or jaundice and no palpable lymphadenopathy. His abdomen was mildly distended, with epigastric tenderness on palpation. Hepatomegaly with point tenderness 3cm below the right costal margin was found. The rest of the exam was normal. Laboratory: Hemoglobin was 14.4 g/dL, WBC 26 000/uL with no bands, 22100/uL neutrophils, 1300/uL lymphocytes, no eosinophils, no basophils, and 1820/uL monocytes. Platelets were 429 000/uL. PT was 15 sec, PTT 30 sec with an INR 1.26. Total bilirubin was 2.9 g/dL with a direct bilirubin of 1.8 g/dL. Alkaline phosphatase was 307 UI/L (20-140 UI/L) with an albumin of 2.8 g/dL (3-4 g/dL). Sodium was 134 mEq/L (135-145 mEq/L), potassium 4.4 mEq/L (3.5-5.5 mEq/L), and chloride was 94 mEq/L (96-106 mEq/L). Imaging: A chest X-ray was performed, revealing elevation of the right hemidiaphragm (Image A). An abdominal CT scan without contrast revealed an approximately 12-15cm in diameter hypodense lesion with well-demarcated borders in the right hepatic lobe (Image B). Stool ova and parasite was performed (Image C). UPCH Case Editors: Carlos Seas, Course Director / Mario Suito, Associate Coordinator |

|

Discussion: US-guided percutaneous catheter drainage (PCD) of the liver lesion was performed (Video), revealing an anchovy paste-appearing fluid (Image D). Abscess direct microscopy for ova and parasites (O&P) was negative. Galactose/ Galactose- N-acetylcysteine (Gal/GalNAC) lectin antigen from the abscess was positive, as well as total serum anti-Gal/GalNAC antibodies for Entamoeba histolytica antibodies, confirming the diagnosis. Image C shows a cyst of E. histolytica in the stools, featuring a rounded structure with three nuclei (lugol stain). An amebic liver abscess (ALA) is the most common extra intestinal complication of Entamoeba histolytica infection. The disease remains prevalent in developing nations, particularly in rural areas with poor sanitation in India, South America, and Africa (1). ALA is 10 times more common in men between 30-50 years than in women and it tends to be more severe in older patients (2, 3). Alcohol consumption is a major risk factor (4), and the right lobe of the liver is involved in 80% of cases, usually solitary with variable size (5). ALA is the most common cause of liver abscesses in the developing world. This disease is caused by E. histolytica trophozoites that invade the liver through the portal circulation after ingestion of contaminated food or water by E. histolytica cysts, which hatch in the small intestine and penetrate the colonic mucosa, where they cause amebic colitis (5). Unlike pyogenic liver abscesses, ALA is non-suppurative and consists of necrotic hepatocytes and cellular debris caused by the phagocytic ingestion of cells in bites, also known as ‘’trogocytosis-like’’ (6). ALA is classified into three clinical forms: subacute mild, acute aggressive and chronic indolent. The most common (80%) is the subacute mild form, with moderate symptoms and good response to medical therapy. Acute aggressive ALA usually presents with a rapidly progressive course and high risk of rupture. Chronic indolent ALA shows prolonged symptoms, thick fibrotic walls, and potential for secondary bacterial infection (5). The classic clinical presentation includes fever, right upper quadrant pain, and hepatomegaly. Jaundice and pleuropulmonary symptoms occur in a minority of cases (7). Complications arise from rupture, secondary infections, or vascular events. Rupture occurs in 6–40% of cases and can lead to peritonitis, pleural empyema, hepatobronchial fistula, or pericardial tamponade (5, 8). Vascular complications include thrombosis of the hepatic and portal veins, leading to ischemia, portal hypertension, and Budd-Chiari syndrome (6). The differential diagnosis of the liver lesion includes pyogenic liver abscess, cystic echinococcosis, hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae infection, and primary liver malignancy. Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation, imaging such as ultrasound or CT scan, and serological, antigenic, or molecular tests. Serology is of limited use in endemic countries due to the high seroprevalence (1, 8). Abscess drainage confirms the diagnosis by finding the classic “anchovy paste” aspirate and, more specifically, Gal/GalNAC lectin antigen detection. A possible alternative to diagnostic drainage is serum antigen detection, which is highly sensitive but not routinely available. Stool O&P is neither sensitive nor specific (5). The first-line treatment for ALA is metronidazole 500–750 mg TID for 7–10 days, followed by a luminal amebicide to prevent recurrence (6). Most uncomplicated cases respond to antibiotics alone. However, percutaneous drainage (PCD) is required for: 1) large abscesses (>5–10 cm), 2) non-resolving symptoms after 72–96 hours, 3) high-risk locations (left lobe, subcapsular, caudate lobe), 4) secondary infection or rupture. Surgical drainage is reserved for cases with extensive peritonitis or failure of PCD (1, 6). Our patient had a big abscess that merited drainage. He is receiving metronidazole with complete resolution of symptoms; fever disappeared after 2 days of antibiotic treatment. References |