At Sophia P. Kingston Elementary in Selma, a new kind of classroom is coming to life: one that starts with a seed, thrives in the soil, and grows through the hands of educators.

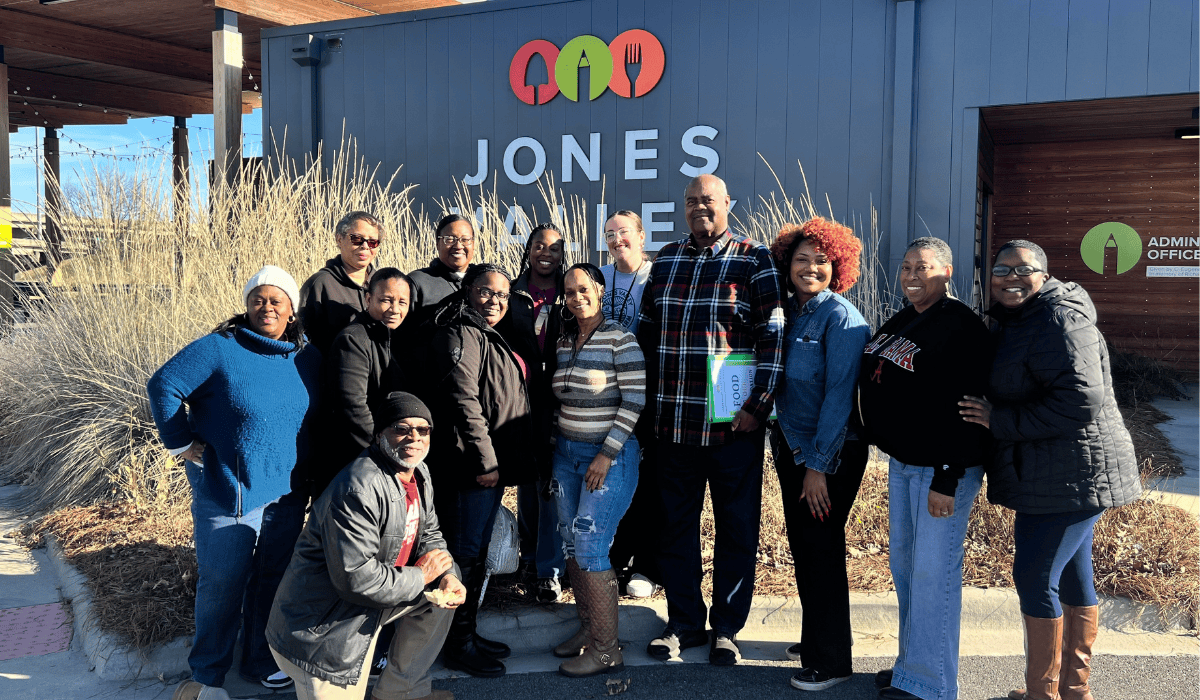

This transformation is part of a collaborative effort between Live HealthSmart Alabama and Jones Valley Teaching Farm, designed to bring sustainable, food-based education to schools in Alabama through hands-on training and community-rooted strategies. The initiative is part of Live HealthSmart Alabama’s Good Nutrition program, which supports healthy choices by increasing food access and providing nutrition education.

The goal is to empower teachers with the knowledge and tools to integrate gardening and culinary learning into their classrooms, creating opportunities for students to engage with food in a more meaningful way. Local partners, including Sophia P. Kingston Elementary, the surrounding community, and Selma-based brick manufacturer Henry Brick, play a key role in supporting this initiative.

From Birmingham to Selma: A partnership takes root

The partnership began in mid-2023 when Live HealthSmart Alabama reached out to Jones Valley Teaching Farm with a vision: help bring a teaching garden to Sophia P. Kingston Elementary as part of their broader community work in Selma.

For Leah Hillman, Director of Educational Programs and Partnerships at Jones Valley, the timing was perfect.

“It was around the time we were building out our consultation and training packages,” Hillman said. “What really sold us was Live HealthSmart Alabama’s holistic approach and commitment to health and wellness within the community, specifically nutrition education, access, policy, and neighborhood beautification efforts.”

That shared philosophy set the foundation for a rich and collaborative relationship—one that quickly moved to hands-on work in Selma. The approach was simple: provide educators with a deep, practical understanding of food-based education so they can tailor it to their environments and students.

For the teachers at Sophia P. Kingston Elementary, the experience began with immersive site visits to Jones Valley’s campuses in Birmingham. These visits included tours of school-based teaching farms, opportunities to observe garden lessons in action, and plenty of time for dreaming and brainstorming.

“Those tours are important because they allow people to see the scale and rhythm of what we do,” said Hillman. “They get to imagine the possibilities.”

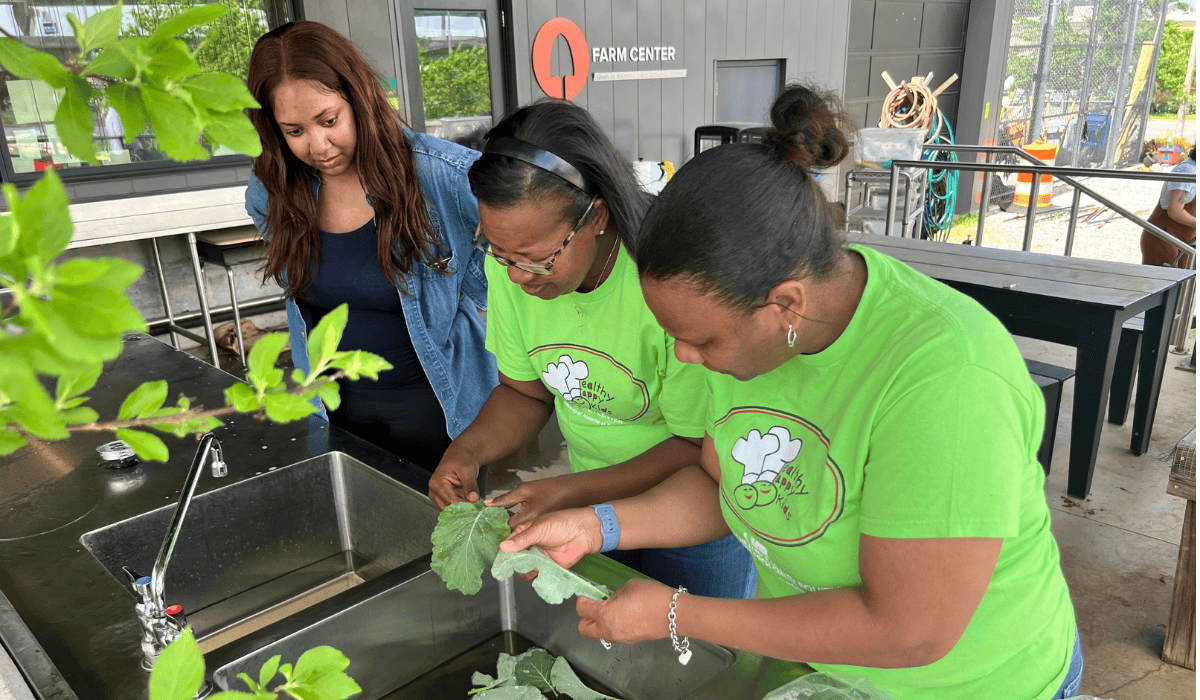

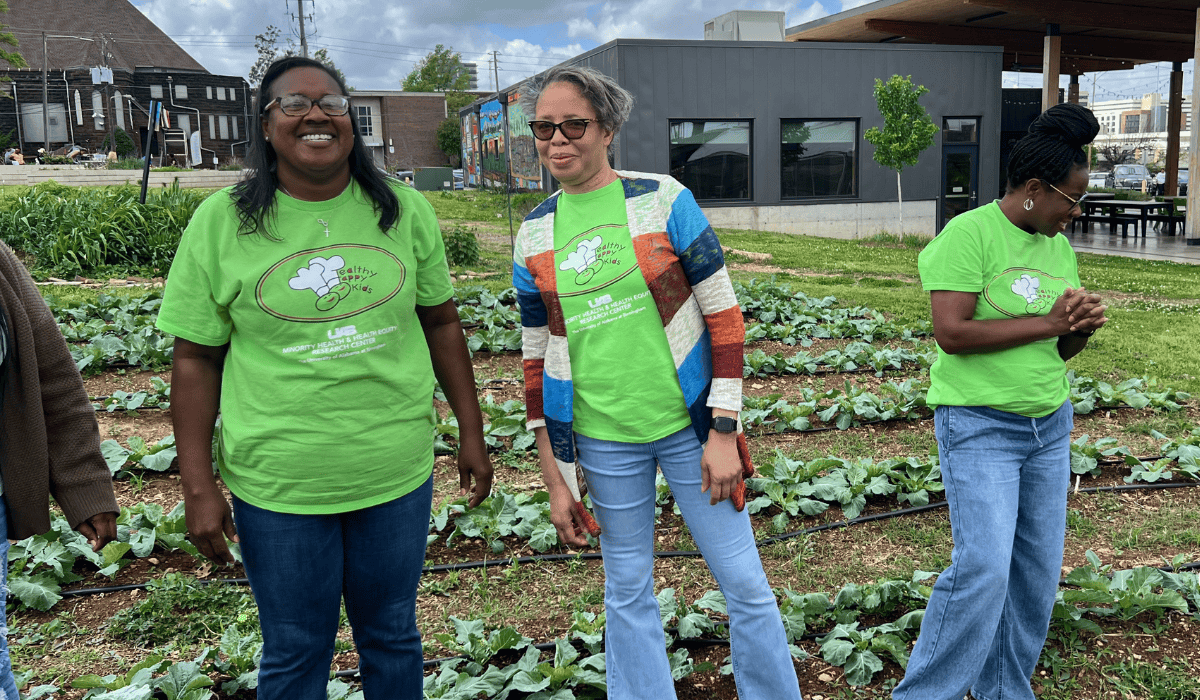

Following the tours, teachers participated in a series of three workshops tailored to their needs. Each session focused on tangible, transferable skills, including how to build and manage a school garden, conduct culinary lessons, deliver outdoor curriculum, and adapt existing classroom content to hands-on, food-centered learning.

In one memorable workshop, teachers practiced an early childhood math lesson using fruit to count. “We were doing this lesson demo around counting to ten using fruit in ten frames as if we were kindergarteners or first graders,” Hillman said. “It was super fascinating to hear teachers, in that moment, spout off different ideas for how they could adapt it or take it to the next level. They were already tuned in and thinking about how they’d conduct the lesson in their own classrooms.”

Beyond practical training, the program also emphasizes a core value: it’s okay to fail.

“We really hone in on the idea that it’s okay to make mistakes,” Hillman said. “You often learn more from failing than you do from doing it right the first time. That’s something we want teachers to feel comfortable with and to pass on to their students, too.”

This mindset builds resilience in both educators and the children they teach. When students are encouraged to try, fail, and try again, they’re more likely to stay engaged and grow from the experience. That kind of hands-on, real-world learning is exactly what food-based education is designed to offer. It also opens the door to deeper conversations around food, culture, and community.

“Different communities interact with food differently,” Hillman said. “When you bring food into the classroom or onto a school site, it opens up these beautiful opportunities to connect and share experiences. Whether we do something the same or differently, there’s so much we can learn from each other through food.”

Growing a healthier future, one garden at a time

This sense of connection, as described by Hillman, is already being felt in Selma—not only in the classroom but across the broader community. Pastor John Goings, from Water Avenue Baptist Church, attended all of Sophia P. Kingston Elementary’s training sessions with Jones Valley Teaching Farm, volunteering to maintain the school’s garden. Since the training, he has been inspired to start a community garden of his own.

“I believe in starting with the youth because whether we train them or not, they are our future,” said Goings. “Training them to learn the importance of taking care of something as simple as a plant will help them understand the importance of taking care of each other. It will help them grow as they learn to depend on each other to ensure that the garden is a success because none of them can do it alone. They will help their classmates learn and grow, which in turn helps the community learn and grow closer together as they become young adults.”

For Live HealthSmart Alabama, this partnership is a powerful example of how Good Nutrition can be woven into the fabric of a school day—not just through meals, but through experiences that help students build lifelong relationships with food, health, and the environment.

By investing in educators first, the initiative lays a foundation for sustainability, ensuring that what’s planted in the soil and in the classroom has the chance to grow.

“This kind of work takes time,” said Hillman. “But when you see teachers excited and ready to bring it into their classrooms, that’s when you know the momentum is real.”

In Selma, the seeds of change are already sprouting.