| 2005 Case #12 |  |

|

|

The Gorgas Courses in Clinical Tropical Medicine are given at the Tropical Medicine Institute at Cayetano Heredia University in Lima, Peru. For the past 5 years, we have been pleased to be able to share interesting cases seen by the participants during the weeks of the year one of our courses is in Session. Each August we run one of our 2-week refresher courses for those with some previous training in tropical medicine. Each case includes a brief history and digital images pertinent to the case. A link to the actual diagnosis and a brief discussion follow. We hope you have enjoyed the 2005 series of live cases each week from Peru. The 2006 Gorgas Diploma Course runs annually in February and March and we will be posting next year?s case series at that time. In addition to the 2005 cases on the Gorgas website, the 2004 case series is now available for full CME credit at no charge at http://www-cme.erep.uab.edu/onlineCourses/Gorgas04/HomePage/GorgasHome.htm. |

| The patient was seen on the 36-bed tropical disease unit of the Tropical Medicine Unit at Cayetano Heredia National Hospital. We thank Dr. C?sar Salinas for providing the pathological images and Miss Carmen Castro for providing the fungal images. |

History: 59 yo white male with 20 year history of rectal prolapse, and 11 month history of a papular lesion in the anal margin that evolved to a nodule, and ulcerated over the next few months. Bloody stools and anorectal pain developed also. Six months prior to admission he had 2 surgical interventions to repair the rectal prolapse, with temporary improvement of symptoms. Two months prior to admission the patient was transferred to the National Cancer Institute in Lima where malignancy was ruled out. Patient then was sent to the outpatient clinic of the Tropical Medicine Institute. No fever, weight loss or fatigue. History: 59 yo white male with 20 year history of rectal prolapse, and 11 month history of a papular lesion in the anal margin that evolved to a nodule, and ulcerated over the next few months. Bloody stools and anorectal pain developed also. Six months prior to admission he had 2 surgical interventions to repair the rectal prolapse, with temporary improvement of symptoms. Two months prior to admission the patient was transferred to the National Cancer Institute in Lima where malignancy was ruled out. Patient then was sent to the outpatient clinic of the Tropical Medicine Institute. No fever, weight loss or fatigue.

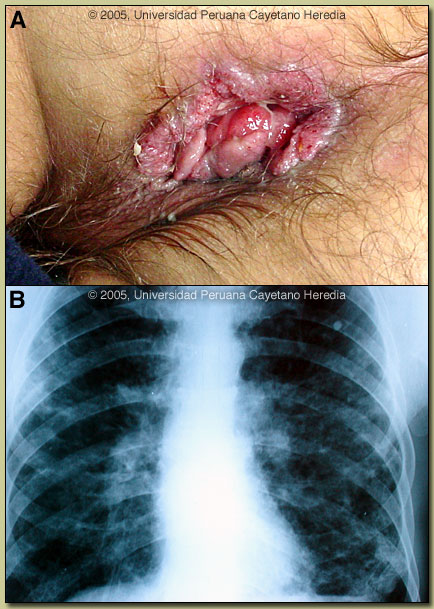

Epidemiology: Born and has spent his entire life as a forestry worker in the high jungle regions of Peru. Uses tree leaves as toilet paper. Tobacco and marijuana smoker. Cocaine abuse in the past. No personal history of TB but had an exposure 1 year ago. Physical Examination: Afebrile; oral mucosa clear; absence of an inferior tooth. No significance lymphadenopathy. Crackles in lower lung fields. No visceromegaly. Anal ulcer of 4 x 2 cm with raised borders and granular background, non-tender, no discharge [Image A]. Laboratory Examination: Hematocrit 46. WBC 6,600 with 62 neutrophils, 22 lymphs, 13 monos, 3 eos, no bands. Glucose 137. ALT, AST, Alkaline phosphatase, urine, urea, creatinine and electrolytes normal. VDRL, HIV ELISA, and HbsAg negative. Stools negative for ova and parasites. CXR showed bilateral interstitial and alveolar lesions [Image B]. Sputum AFB negative X3.

|

| Diagnosis: Paracoccidioides brasiliensis infection (chronic form). |

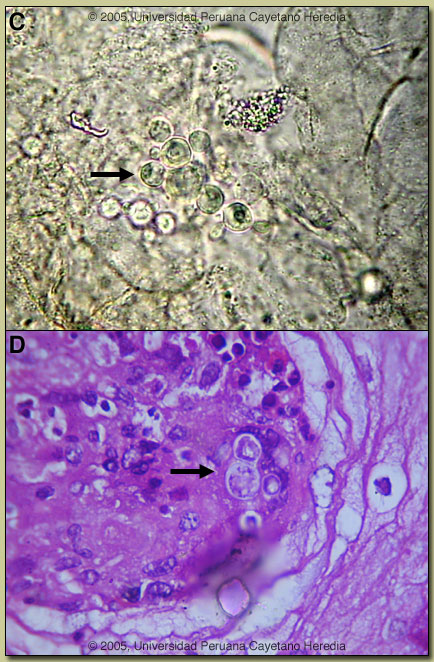

Discussion: A KOH preparation of a direct scraping of the anal lesion showed several spherical cells 10-40 microns in diameter with a thick birefringent cell wall surrounded by several peripheral buds joined by narrow necks [Image C]. When completely surrounded by buds a so-called “pilot-wheel” pattern occurs. Direct scrapings or aspirates will be positive in the vast majority of cases of paracoccidioidomycosis with mucosal or cutaneous lesions. Sputum KOH was negative. A biopsy of the anal lesion showed pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia with lymphocytic infiltrate and giants cells. Large yeast forms of Paracoccidioides were observed [arrow Image D]. Hyphal forms are not seen in tissue in paracoccidioidomycosis. Tissue and sputum cultures are pending. Discussion: A KOH preparation of a direct scraping of the anal lesion showed several spherical cells 10-40 microns in diameter with a thick birefringent cell wall surrounded by several peripheral buds joined by narrow necks [Image C]. When completely surrounded by buds a so-called “pilot-wheel” pattern occurs. Direct scrapings or aspirates will be positive in the vast majority of cases of paracoccidioidomycosis with mucosal or cutaneous lesions. Sputum KOH was negative. A biopsy of the anal lesion showed pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia with lymphocytic infiltrate and giants cells. Large yeast forms of Paracoccidioides were observed [arrow Image D]. Hyphal forms are not seen in tissue in paracoccidioidomycosis. Tissue and sputum cultures are pending.

The differential diagnosis for the lung disease includes: TB, histoplasmosis, lymphoma, cancer and cryptococcosis. The anal lesion must be differentiated mostly from malignancy. In general, cutaneous or mucosal lesions of paracoccidioidomycosis are painful while those of other infections are not. The lungs are the primary site of infection in paracoccidioidomycosis. In 30% of patients, lungs are the only organs affected, but in necropsy studies over 90% of all patients have pulmonary involvement. The most typical radiographic pattern is bilateral mixed infiltrates (alveolar and interstitial), mainly located in the middle and lower lobes. Interstitial lesions may have a miliary, nodular or fibronodular patterns. Other patterns observed in these patients are hilar and mediastinal lymph node enlargement, cavities, and calcified lesions. Patients with oral and skin lesions may not have respiratory symptoms, but almost always have pulmonary involvement. Extrapulmonary disease is found in over 70% of cases and may involve skin, mucous membranes, lymph nodes, adrenals, abdominal organs and CNS (in 10%). Bacterial superinfection of ulcerative oral lesions is more common than with oral ulcers due to mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. This case is representative of the chronic form (adult type) of the disease, which is believed to represent reactivation of latent infection. This type represents approximately 94% of all cases in the experience at our institute (94 patients, up to 2001), and approximately 85% in the Brazilian series (Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2003;36:455-9). In our experience the male:female ratio in chronic paracoccidioidomycosis is 20:1. TB coexists in up to 10% of patients with paracoccidioidomycosis. Cavitation and pleural effusion are less commonly seen than in TB. Paracoccidioidomycosis, also known as South American blastomycosis is found in humid forested or lush green areas of the Americas from Southern Mexico south to Uruguay and Argentina. It appears to be most common in Brazil. The exact habitat of the organism is unclear but transmission is described as being entirely by airborne inhalation. However, we have observed cases with only oral lesions apparently associated with the use of tree leaves contaminated with fungal spores as toothpicks. Similarly we have seen a number of cases with anal lesions in patients who frequently use leaves as toilet paper though no rigorous studies have been carried out. Primary pulmonary infection may be asymptomatic and self-limited but even with treatment will produce at least moderate pulmonary fibrosis. Rural adult males agricultural workers between 30-60 years of age are most affected by the infection. Travelers spending less than 6 months in an endemic area are unlikely to acquire paracoccidioidomycosis. Sulfonamides, ketoconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B are all effective therapies. Amphotericin should be reserved for severe cases. While itraconazole 100 mg/day for 6 months or so is regarded as the treatment of choice, in the developing world setting ketoconazole is likely equally effective and is usually less than half the cost. However, 12 months of therapy with ketoconazole is generally recommended. Paracoccidioidomycosis is always a severe infection that may relapse even after prolonged treatment so always needs to be treated and followed up aggressively. In this case the initial therapy was likely of too short a duration as only 4 months of itraconazole was taken. We gave the patient 10 days of Amphotericin B due to the destructive nature of the anal lesions and will give itraconazole for a minimum of 6 months.

|