| 2007 Case #4 |  |

|

| The following patient was seen in the inpatient department of the 36-bed Tropical Disease Unit at Cayetano Heredia National Hospital. We thank Dr. Alejandro Bussalleu for providing his endoscopic images and assistance with the case. |

|

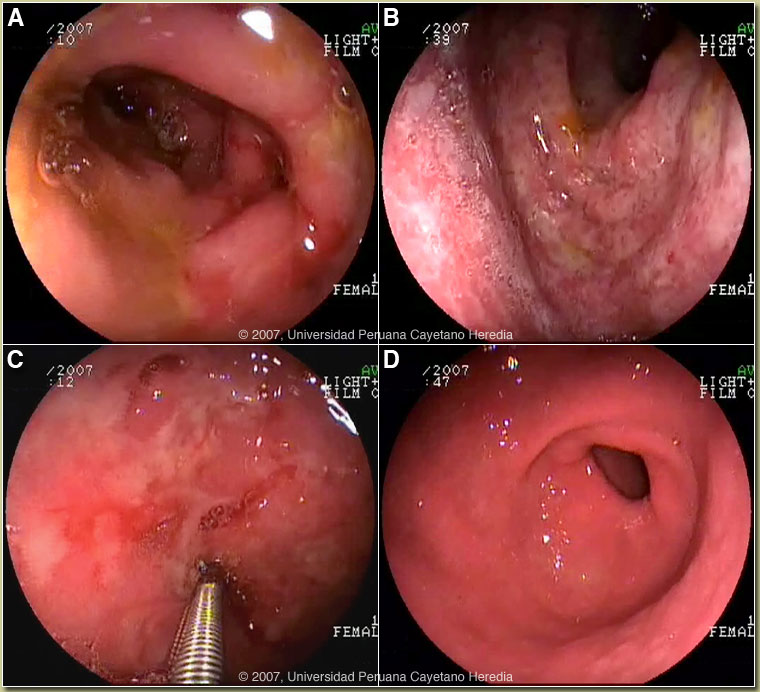

History: 16-year-old female, presented with a 1-month history of decreased appetite, burning epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting (three episodes per day, always after eating). Ten days of treatment with natural remedies and then ranitidine produced some relief. Two days before admission, she developed hematemesis and then black, tarry stools. She reports a 5 kg weight loss during the illness. No fever or rash. Normal periods with last one a month ago. Hepatitis A infection ten years ago. Epidemiology: She was born in Tingo María in the jungle and is currently a high school student in Lima. No known TB exposure. No drug or alcohol abuse. No illness in immediate family. Physical Examination: Pale, appearing poorly nourished, in mild acute distress without icterus. BP 90/60, HR 104, RR 22, T 37°C. No rash or petechial lesions on skin or mucosa. Chest clear. Abdomen: normal bowel sounds; mild tenderness in the epigastric region without rebound or guarding; no hepatosplenomegaly. CNS: alert and oriented. Laboratory Tests: Hematocrit 17.4, Hb 5.8, WBC 7.4 with normal differential. Platelets 341,000. INR 1.26. Total bilirubin 0.4, AST 52, ALT 73. Albumin 1.5. Abdominal ultrasound was unremarkable. Chest x-ray normal. Upper GI endoscopy: congestion and edema was present throughout the duodenum. The mucosa of the bulb and the second portion of the duodenum showed erythema and multiple erosions [Images A and B]; ulcers were present in the second portion of duodenum [Image C]; and nodular gastritis was seen in the antrum [Image D]. Colonoscopy was normal. |

| Diagnosis: Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection syndrome. HTLV-1 infection. |

|

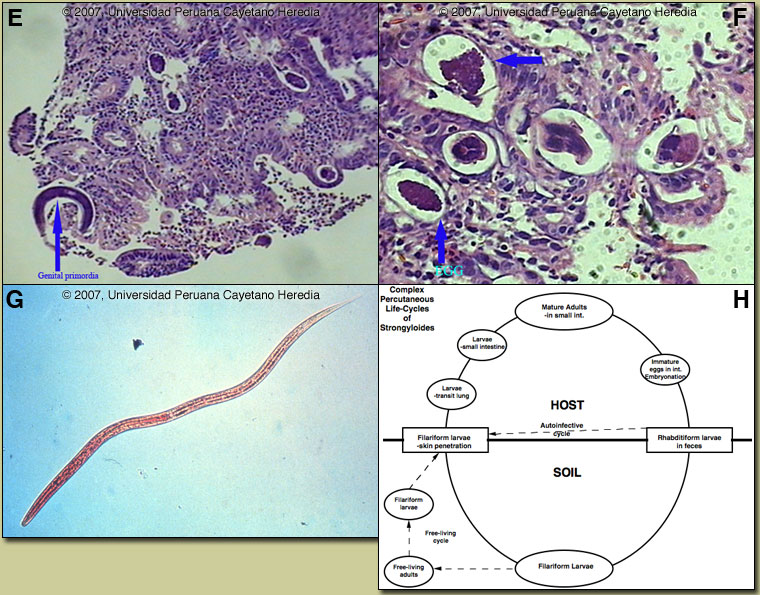

Discussion: The duodenal biopsy showed an inflammatory infiltrate and female strongyloides larvae [arrow Image E] in the submucosa. Image F shows eggs and adult strongyloides worms in cross-section. On stool examination large numbers of filariform larvae of strongyloides were seen [Image G]. No larvae were seen on sputum examination. HTLV-1 ELISA and Western blot were positive.

Strongyloides stercoralis has a complex life cycle [Figure H]. Three separate developmental stages play a role in the life cycle; adult worms, rhabditiform larvae, and filariform (infectious) larvae. Three alternative clinically important modes of replication exist. In the internal sexual cycle the adult female, resident in the small intestine, lays small numbers of eggs that hatch almost immediately. The resulting rhabditiform larvae are passed in the stool, mature in the soil to infective filariform larvae, and penetrate the skin of a new human host. After migration through the lung, the larvae crawl over the glottis, are swallowed and complete development in the jejeunum. In the free-living cycle, rhabditiform larvae may instead develop in the soil into sexually active adults, thus creating an environmental reservoir of adult worms. Each generation of this external sexual cycle includes a new cohort of infectious filariform larvae ready to re-enter the parasitic cycle in humans. Finally, in the autoinfective cycle, infectious filariform larvae develop from rhabditiform larvae while still in the intestine. Penetration of the colon or the anal skin by filariform larvae allows re-infection of the same host. The autoinfective cycles, which normally result in low-grade chronic infection in normal hosts, should be distinguished from the hyperinfection that occurs in immunocompromised hosts as a result of massive potentially fatal autoinfection with dissemination of larvae to numerous distant organs. Clinically, infection is often asymptomatic. Purely intestinal infection may cause mild to severe abdominal symptoms. Adult females in the small intestinal mucosa may cause mild to severe inflammation. In autoinfective cycles, migrating larvae may cause serpiginous skin lesions (larva currens), especially around buttocks, or lung inflammation. Opportunistic behavior in immunocompromised hosts with hyperinfection may result in wide dissemination to extraintestinal organs, including the central nervous system, pulmonary hemorrhages, sepsis, and death. Inflammation and necrosis may occur in any organ and intestinal perforation may occur. Predisposing factors include malnutrition, corticosteroid therapy, malignancy, and HTLV-1 (but not HIV) infection. Patients with strongyloides hyperinfection may have eosinophilia in the early stages of disseminated disease, but are most often eosinopenic by the time of clinical presentation. In Peru 86% of patients who present with strongyloides hyperinfection are HTLV-1 positive [Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999 Jan;60(1):146-9]. The prevalence of HTLV-1 in South America is generally underappreciated, normally being associated with Japanese and Caribbean populations. In Perú, the disease is highly endemic (2-3% seropositivity) in Andean areas of the country in Quechua populations who have had no contact with Japanese immigrants to the country. Other South American countries with significant rates of HTLV-1 include Brazil, Colombia, and Ecuador. We have seen over 800 infected families to date at the Tropical Medicine Institute in Lima. There are only a small number of case reports in the literature of massive gastrointestinal bleeding due to strongyloidiasis. This may be due to the difficulty in proving cause and effect in patients who often have concomitant chronic underlying severe disease of a number of etiologies or are on corticosteroid therapy. Our patient was young, not on any current or recent medication, and had no underlying serious disease. While the demonstration of larvae in stools is often difficult in simple intestinal infection, in hyperinfection countless larvae are easily demonstrated. Sputum and other body fluids may be positive as well. Fecal culture may be necessary. The distribution of strongyloides is worldwide, but is especially common in Southeast Asia and moist forested areas of the Amazon basin. In the US there is an endemic focus in Appalachia. Our patient was treated with IV fluids and transfusion. Ivermectin was administered for two days and no bleeding has been observed since admission. Nausea and epigastric pain resolved, and complete oral intake was resumed after six days.

|