| 2010 Case #10 |  |

|

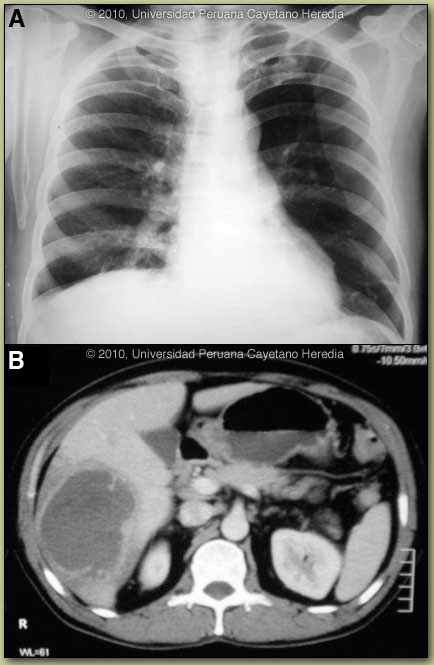

| Diagnosis: Liver abscess due to Entamoeba histolytica. |

|

E. histolytica is a single celled intestinal protozoan parasite that is transmitted from human to human via the fecal-oral route. Infectious cysts are excreted into the environment and are ingested by new human hosts where only a small proportion of the cysts will excyst to become tissue invasive. Thus, 90% of infections result in asymptomatic disease and up to 10% of the world’s population may be infected. The 10% of infections that are invasive mostly cause dysentery and colitis and in only 1% of total infections is there extra-intestinal dissemination, mostly to liver and brain. Direct extension of amebic liver abscesses (ALA) may result in pleural and pericardial infection and direct extension from the rectum may cause perianal cutaneous disease. The non-pathogenic E. dispar and E. moshkovskii, which are 10 times more common than E. histolytica in stool specimens, have cysts which appear identical by microscopy but never become invasive. Other non-pathogenic ameba, which are morphologically distinct include: E. polecki, E. hartmanni, and E. coli. Typical presentation of ALA in Perú includes an insidious onset over several weeks, fever in 90%, weight loss in about half, concomitant diarrhea in about a third, abdominal pain in over 90%, tender hepatomegaly in 30-50%, and jaundice in less than half. There is a male predominance and most infections are in 20-50 year olds. General laboratory findings include an elevated white count with left shift in almost all patients, mildly elevated transaminases and alkaline phosphatase, and sometimes mildly elevated bilirubin. As most patients at the time of diagnosis of ALA do not have a concurrent intestinal infection with Entamoeba histolytica, stool examination is positive in less than 10% of cases. The noninvasive diagnosis of ALA is challenging. Serology is positive in approximately 90-100% of invasive amebiasis cases either intestinal or extra-intestinal but only become positive by the second week of illness. ELISA is currently the most common commercially available antibody detection test used. Anti-amebic antibodies are not present in non-invasive or asymptomatic infection and are not present in E. dispar. Using a commercial kit, the Gal/GalNAc lectin antigen of E. histolytica can be detected in serum in 96% of ALA cases and is present in abscess fluid about 50% of the time. As with stool microscopy, antigen is infrequently present in stool in ALA cases [J Clin Microbiol. 2000 Sep;38(9):3235-9]. However, patients with amebic intestinal infection with another cause for a liver lesion may also have serum antigen present though this is not a frequent occurrence. Detection of antigen in the abscess fluid, however, is a definitive finding. Serum antigen detection is significantly affected by treatment with a negative test result after one week of treatment in 82% of patients; the test should be ordered before starting antibiotics or soon thereafter. A recent study has shown that when both tests are performed, E. histolytica DNA can be detected either in urine or saliva in 97% (92/95) of ALA cases by real-time PCR [J Clin Microbiol. 2010 Aug;48(8):2798-801]. DNA was present in serum in only 49% of ALA cases. Imaging typically shows an elevated R hemi-diaphragm, as in our case. On ultrasound or CT scan a single abscess is found in 90% of cases. As spread from the intestine occurs via the portal circulation it is thought that initial small multiple abscesses often coalesce into one large abscess within a short period of time. Differential diagnosis includes pyogenic liver abscess, which is much more common in older individuals but usually is identical on ultrasound or CT scan and presents with a similar clinical picture. Patients with echinococcal cysts usually have distinctly different CT scan appearances [see Gorgas Case 2003-03] and are rarely febrile, ill-appearing or toxic. Hydatid cysts often are complex with daughter cysts and distinct internal septations. Some hepatomas may also appear similar on CT scan. Treatment is with either metronidazole (10 days) or tinidazole (5 days), plus a lumen active agent such as paromomycin or diodoquinol. Oral therapy is the preferred route. Therapeutic aspiration of an amebic abscess is not usually necessary. Indications include no resolution of fever by Day 4-5 of anti-protozoal therapy, large abscess (>10 cm), or left lobe location (danger of pericardial invasion). Response to therapy is monitored by resolution of fever. The hepatic cavity created by the abscess may remain detectable by ultrasound or CT for more than 6-12 months and is not an indicator of treatment success or failure.Our patient remained febrile after 4 days of combined antibiotic and anti-amebic therapy and with a 9 cm cyst, aspiration and drainage for both diagnostic confirmation and therapeutic effect was undertaken. His fever then resolved within 24 hours of the procedure. |

Discussion:

Discussion: