Leading diabetes care innovation

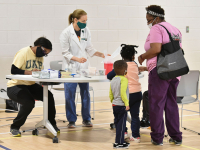

When the UAB School of Nursing opened its nurse-managed PATH (Providing Access to Health Care) Clinic in 2011 its goal was to help patients with no health insurance, many of whom were homeless, without access to health care.

When the UAB School of Nursing opened its nurse-managed PATH (Providing Access to Health Care) Clinic in 2011 its goal was to help patients with no health insurance, many of whom were homeless, without access to health care.But its founder, Associate Dean for Clinical and Global Partnerships and Professor

Cynthia Selleck, PhD, RN, FAAN, had her sights set on expanding the clinic to provide chronic disease management for uninsured and underinsured patients with diabetes and began looking for innovative ways to make this a reality. In 2012 the School received a three-year, $1.4-million Nurse Education Practice Quality Retention (NEPQR) grant from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to develop and implement an interprofessional collaborative health-care transition clinic at the PATH Clinic to improve the quality of care and outcomes for underserved patients with diabetes recently discharged from UAB Hospital. It, along with supplemental funding from the UAB Health System, brought together a team that included nurses, physicians, nutritionists, social workers and more, to provide follow-up and continuing care, along with access to testing supplies and medications, for these patients.

“Diabetes is an enormous health issue in Alabama,” said Will Ferniany, PhD, CEO of the UAB Health System. “More than a third of our non-maternity patients in UAB Hospital suffer from, and nearly half of our patient days are associated with, poor blood sugar control. When you factor in that a large number of these patients lack insurance, and they often have no access to medical care or diabetic medications and supplies outside of the hospital, providing a source of ongoing care with access to needed medications and testing supplies is a win-win situation.”

Selleck said data show the clinic has resulted in improved patient outcomes, decreased hospital admissions and significantly reduced hospital costs.

“We followed 218 unique patients who used the clinic for at least a year. Not only did the days they spend in the hospital decrease significantly, there was a 60 percent decrease in the cost to take care of them when they were hospitalized,” she said.

UAB Hospital Chief Nursing Officer, Assistant Dean for Practice at UAB Hospital and Assistant Professor Terri Poe, DNP, who was instrumental in launching the PATH Clinic diabetes project when she was a DNP student in the School, is impressed with the outcomes so far.

UAB Hospital Chief Nursing Officer, Assistant Dean for Practice at UAB Hospital and Assistant Professor Terri Poe, DNP, who was instrumental in launching the PATH Clinic diabetes project when she was a DNP student in the School, is impressed with the outcomes so far.“These patients still visit our emergency department but they come for true ‘emergency’ reasons, not for clinic-type visits related to their diabetes,” she said. “And, when they do come in they are not as likely to be admitted. The PATH Clinic has helped reduce the patients’ complications from diabetes, thus decreasing the cost to the health system.”

“This clinic has an incredible impact on the quality of life for our patients,” said Clinic Nurse Practitioner, MSN Program Director and Assistant Professor Michele Talley, PhD, CRNP, ACNP-BC. “The quicker we get their blood sugars under control the quicker we reduce other complications and impact their health long term.”

Survey data also show the PATH Clinic team, which comprises clinical and non-clinical providers, has been quite successful. Because the project was originally funded with a NEPQR grant, there was a tremendous amount of team evaluation required.

For even the most seasoned providers, it has been a valuable learning curve.

“Everyone, through this project, learned the best ways to function as a collaborative interprofessional team to provide quality, patient-centered care, including shared patient-centered problem solving,” Selleck said.

In Summer 2015, the PATH Clinic moved onto the UAB campus into the Medical Towers building, giving the clinic more space, adding extra clinic days and providing a more convenient location for patients.

“If there is something wrong with the patient and they need care right away from the emergency room, we are a lot closer than we were,” Talley said.

With the success of the PATH Clinic, other faculty are using the model as a starting point for other nurse-managed interprofessional transitional care clinics for other conditions and populations.

Innovative heart failure care

For a number of years, UAB Hospital has monitored heart failure patient outcomes, said Connie White-Williams, PhD, RN, FAAN, Director of the Center for Nursing Excellence and Assistant Professor. Traditional quality efforts have only modestly improved inconsistent length of hospital stays and higher-than-desired readmission rates.

For a number of years, UAB Hospital has monitored heart failure patient outcomes, said Connie White-Williams, PhD, RN, FAAN, Director of the Center for Nursing Excellence and Assistant Professor. Traditional quality efforts have only modestly improved inconsistent length of hospital stays and higher-than-desired readmission rates.Interim Chair of the Department of Acute, Chronic and Continuing Care and Professor Maria Shirey, PhD, MBA, MSN, RN, NEA-BC, ANEF, FACHE, FAAN, collaborated with White-Williams as part of the UAB Nursing academic practice partnership to open a nurse-managed, interprofessional transitional care clinic for heart failure patients recently discharged from UAB Hospital. The goal is to reduce 30-day readmission rates and improve access to care for the underinsured and medically underserved.

“This builds on the PATH Clinic’s model with modifications to address the care complexity requirements for heart failure patients,” Shirey said. “We hope to replicate its outstanding outcomes.”

The clinic has been open for six months, is supported by a $ 1.5 million Nurse Education Practice Quality Retention (NEPQR) grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and comprises an interprofessional team of nursing, medicine, social work, health services administration and health information technology professionals.

Transitional care coordination begins while patients are in the hospital. A clinical nurse leader serves as case manager, coordinating care across the health care continuum. Nurse practitioners and other providers see patients in clinic and hospital rounds on eligible heart failure inpatients. Team members also evaluate patients for palliative care eligibility and contact them within 48 hours of discharge to ascertain their well-being and confirm scheduled follow-up visits.

“Our goal is to get these patients into evidence-based therapies, reverse their heart failure if we can and educate them on how to self manage,” Shirey said.

“We also identify their barriers to compliance to help them be successful,” said Clinic Nurse Practitioner and Instructor Shannon DeLuca, MSN, CRNP, AGACNP-BC.

Early results are encouraging, Shirey said. All patients referred to the clinic are seen within seven days of discharge. This is an important metric that has contributed to UAB Hospital receiving bronze level recognition from the American Heart Association’s Heart Failure Get with the Guidelines program.

And, Shirey added, the clinic’s patient satisfaction scores are much greater than anticipated. Survey results show 95 percent of office visits resulted in satisfied or very satisfied ratings. Qualitative results also have been impressive. Patients say they feel they can ask questions and are treated with respect.

And, Shirey added, the clinic’s patient satisfaction scores are much greater than anticipated. Survey results show 95 percent of office visits resulted in satisfied or very satisfied ratings. Qualitative results also have been impressive. Patients say they feel they can ask questions and are treated with respect.“This clinic’s approach is different than others in that it is much more patient-centered,” said Vera Bittner, MD, UAB cardiologist and the clinic’s collaborating physician. “They do an excellent job in ensuring that the barriers to treatment are removed as much as possible and, because they follow the patients so closely and see them so frequently, they do an excellent job of keeping patients on their medications.”

The team also is performing well. Team members have been working closely with their evaluators, led by Lisle Hites, PhD, Director of the UAB Center for the Study of Community Health Evaluation and Assessment Unit.

“Preliminary results indicate that successes are emerging as the team matures, resulting in more efficient communication in the interprofessional approach,” Shirey said.

Innovative collaboration doesn’t end within the team. Many patients of the Heart Failure Clinic also receive care in the PATH Clinic. The two coordinate patient visits and share a social worker who is pivotal in helping patients.

“Both clinics have to be creative in finding additional resources for what is an underserved patient population,” Shirey said. “Our shared social worker, Erin Clarkson, is able to help patients with prescription assistance programs, transportation, housing and other needs, and is a common face between the two clinics, which is reassuring for our patients.”

Ferniany said these two clinics are excellent examples of the positive impact for patients and hospitals that can happen when academic health centers partner with schools of nursing.

“These interprofessional transitional care clinics see some of the most complex populations served by UAB’s Academic Health Center and demonstrate the added value of engaging School of Nursing faculty and students to develop patient-centered solutions to chronic care,” said Dean and Fay B. Ireland Endowed Chair in Nursing Doreen C. Harper, PhD, RN, FAAN.

Transitional innovations for Veterans

The School’s newest nurse-managed transition clinic, the VA Mental Health Afterhours Clinic, opened in May 2015. It is a partnership with the Birmingham VA Medical Center, offering appointments for those recently discharged from the Birmingham VA Medical Center or Veterans and their families in acute need, and those who want to avoid emergency department services. It is open on Tuesdays from 1 to 8 p.m.

The School’s newest nurse-managed transition clinic, the VA Mental Health Afterhours Clinic, opened in May 2015. It is a partnership with the Birmingham VA Medical Center, offering appointments for those recently discharged from the Birmingham VA Medical Center or Veterans and their families in acute need, and those who want to avoid emergency department services. It is open on Tuesdays from 1 to 8 p.m.“Within the first two months we saw nearly 75 patients. Anytime we can add additional services to meet the needs of Veterans, it’s a good thing,” said Chair of the Department of Family, Community and Health Systems Professor Teena McGuinness, PhD, CRNP, PMHNP-BC, FAAN.

Led by Instructor Chance Nicholson, MSN, BS, CRNP, PMHNP-BC, RN-BC, the clinic offers follow-ups, walk-in appointments, intakes, assessments, medications, psychotherapy and referrals.

“The idea is to serve patients that may not have been able to be seen by their regular provider and to extend care hours so that individuals who work during the day, who may not be able to take off to come in for their appointment, can be seen. It gives people who really need to be seen the opportunity to fulfill the need they have, hopefully preventing a readmission or preventing them from relying on emergency services,” Nicholson said.

A unique aspect of the clinic is that in addition to Nicholson, staffing the clinic are three mental health nurse practitioner residents. The Mental Health Nurse Practitioner Residency Program was created by a five-year pilot program from the Veterans Health Administration Office of Academic Affiliation to the Birmingham VAMC and UAB School of Nursing.

The patients the residents see are quite challenging, McGuinness said. They have PTSD, panic, mood or anxiety disorders and even mild or moderate dementia. Often these are combined with other chronic conditions, including diabetes, lung disease or high blood pressure. Nicholson supervises the residents and provides clinical expertise and consults on patients when necessary.

The patients the residents see are quite challenging, McGuinness said. They have PTSD, panic, mood or anxiety disorders and even mild or moderate dementia. Often these are combined with other chronic conditions, including diabetes, lung disease or high blood pressure. Nicholson supervises the residents and provides clinical expertise and consults on patients when necessary.“This is an excellent educational opportunity,” he said. “Each time residents see a patient, we are there for support. While there is independence for residents to see patients, there is never a time the resident is without our support should a need arise.”

“The mental health nurse practitioners in this clinic are increasing access to high-quality interprofessional team-based care for some of the most complex Veterans with behavioral health issues and conditions in a more convenient setting,” said Cynthia Cleveland, DNP, RN, NE-BC, Chief Nursing Officer for the Birmingham VAMC.

“The program also has helped our Mental Health Nurse Practitioner Residents see the need to further their education through our Doctor of Nursing Practice Program (DNP),” McGuinness added.