Medical Technologist Hallie Clark, M.S., MLS (ASCP), selects units of blood from the storage cooler in the Blood Bank.

Medical Technologist Hallie Clark, M.S., MLS (ASCP), selects units of blood from the storage cooler in the Blood Bank.

No matter what we look like on the outside, we are all roughly the same shade of red under the skin.

That observation was prompted by a visit to the walk-in storage cooler inside the Blood Bank in UAB Hospital. If you are squeamish at the sight of blood, this is not the place for you. When the door closes, you are surrounded by 1,000 or so units, from hundreds of donors of various ages and ethnicities, each containing 300 milliliters of life-giving fluid that is essentially the same hue.

The space has the same basic layout and dimensions as the coolers you see in gas stations and grocery stores, except this one stocks only a single product in a handful of varieties. There are O, A and B, each in positive and negative, along with a short list of specialty items, including irradiated blood, treated with X-rays to deactivate the donors’ white blood cells, which could be dangerous to babies and patients with compromised immune systems.

See inside Hospital Labs' automated clinical laboratory in the video above, released in 2017 soon after the lab opened.

In fiscal year 2024, the Blood Bank dispensed more than 78,000 units of blood — packed red blood cells, plasma, platelets, whole blood and cryoprecipitate.

“We have so many trauma and cancer patients at UAB Hospital — that’s why we use so much blood,” said Sherry Polhill, MBA, associate vice president for Hospital Laboratories, Respiratory Care and Pulmonary Function Services for UAB Hospital. “We are by far bigger than any other hospital in the state.”

That goes for the entire Hospital Labs operation. The Blood Bank is just one of 37 specialized spaces throughout UAB Hospital and four other major facilities (UAB Hospital-Highlands, the Kirklin Clinic, the Whitaker Clinic, and Gardendale Primary & Specialty Care) and nine satellite locations. Together, they run more than 10 million tests per year. Nearly 73 percent of all the content in UAB’s electronic medical records system comes from Hospital Labs. “It really is quite an amazing operation,” Polhill said. “But it is never just a test or a unit of blood — it is part of a patient’s hospital stay or clinic visit. We never forget that.”

The lab’s results determine what medicine a newly diagnosed cancer patient will receive, whether a patient can be discharged or must stay in the hospital, whether a surgical team needs to get prepped right away for the OR. Polhill’s senior staff spend a good part of their time triaging urgent calls from clinicians making a case for why their patient’s tests are urgent enough to jump the queue. “It can be a stressful environment,” Polhill said. “You have to have the right personality.”

If you close your eyes and imagine what a hospital lab looks like, you might picture rows of white-coated scientists peering into microscopes in silence. In reality, there is continual movement and the whir of high-tech machinery and constant deadline pressure. Every afternoon, thousands of vials of blood drawn at the Kirklin Clinic arrive by pneumatic tube in the main automated clinical lab in the Spain Wallace Building. Over the next hours, as the sun sets, thousands more blood tubes arrive from inpatient units around UAB Medicine. They need to be analyzed and ready for the clinicians who begin their rounds the next morning at 5 a.m. At night, every night, Hospital Labs team members working the second and third shifts keep the results coming — providing about 5,000 test results.

In addition to the morning rounds deadline, on any given day members of Polhill’s team may need to drop everything and rush additional units of blood to an operating room, put on massive gloves to reach into a nitrogen-chilled freezer to prepare a lifesaving cancer therapy for a waiting patient, or spend eight hours or more in a surgical suite, running the machine that helps a lacerated car crash victim survive by cleaning their blood and giving it right back to them.

“Most people just think of the lab as someone drawing their blood, but they don’t get to see the rest of it,” said Gina DeFrank, M.T., M.B. (ASCP), senior director for Lab Medicine and Genetics Labs. “I wish more people could see it.”

That is what this series is all about. Join us as we take a look behind the scenes at just a few of the lab’s roles and meet some of the hospital’s hidden heroes who work here.

Medical Technologist Dennis Quertermous, MLS (ASCP) runs a test on one of UAB's advanced gene sequencing machines.

Medical Technologist Dennis Quertermous, MLS (ASCP) runs a test on one of UAB's advanced gene sequencing machines.

Blood Bank

Like a grocery store manager preparing for the crowds of shoppers before Thanksgiving, Ameenah Bishop, MSHQS, MBA, senior director for Critical Care and Blood Transfusion Services, must constantly worry about the supply chain. A major trauma incident could deplete UAB’s stock of blood in an afternoon.

Every day, the Blood Bank receives shipments from the Red Cross of anywhere from 80 to 150 units, packed on ice, 25 to a box. Additional shipments come in from other suppliers as well. A constant background chorus in the Blood Bank is the drip of melting ice — though it is often drowned by the sounds of platelet agitators, centrifuges, irradiators, tube sealers and all kinds of other equipment.

Sometimes, those regular deliveries are not enough. A heavy schedule of surgery cases, combined with an unusual number of traumas, might send her to the internet — to a site that is essentially “an eBay for blood,” as she described it, where hospitals can arrange to share their supplies.

Bishop’s job is to walk a delicate balancing act. Frozen plasma is not any good in an emergency, so a liquid supply must be kept constantly stocked in the Blood Bank’s storage cooler. But once it is thawed, it is good for only five days. “We can go from fully stocked to wiped out in no time,” Bishop said. Each week, the Blood Bank transfuses more than 100 units of blood to patients with sickle cell disease and has constant requests from across the hospital, including tiny, 15 milliliter aliquots of O negative blood for transfusing babies. The waiting room at the Blood Bank has no patients — but it is generally packed with nurses and other clinicians ready to take blood orders back to their units.

Like many of the more than 530 Hospital Labs employees, Bishop is UAB-trained, with a bachelor’s degree in medical technology, a master’s degree in Health Care Safety and Quality, and an MBA. She was born at UAB Hospital, too. “I’m UAB for everything,” Bishop said.

There are 32 different job descriptions in Hospital Labs, but there are three main ones. Lab techs have a high school diploma. Medical lab technicians have two-year degrees. Medical technologists, like Bishop, have bachelor’s or master’s degrees. In school, Bishop found herself gravitating to the Blood Bank. “I think all med techs have their thing,” she said. “Blood Bank was always my favorite.” Her mother is a nurse, Bishop said, but “I didn’t think I would make a really good bedside nurse, because I’d be in there crying with my patients. This is my way to contribute to health care.”

That does not mean that Blood Bank work is easy. “We have to respond to Surgery and Trauma at a moment’s notice,” said Sherry Polhill, MBA, associate vice president for Hospital Laboratories, Respiratory Care and Pulmonary Function Services for UAB Hospital. “Our Blood Bank team is excellent — they respond under stress, they understand the stress, and the result is they save a lot of lives.”

Molecular Lab Manager Jay Holliday, left, and Senior Director for Lab Medicine and Genetics Labs Gina DeFrank, M.T., M.B. (ASCP), right.

Molecular Lab Manager Jay Holliday, left, and Senior Director for Lab Medicine and Genetics Labs Gina DeFrank, M.T., M.B. (ASCP), right.

Molecular Testing

Gina DeFrank, M.T., M.B. (ASCP), senior director for Lab Medicine and Genetics Labs, has been working in UAB labs for nearly 40 years. “It’s still never boring,” she said. “You get to work with a lot of very intelligent people, and you are always learning something new.” DeFrank’s team works with some of the most advanced tests and machinery available anywhere on the planet.

On a recent tour, DeFrank wove in and out of several different spaces packed with the latest molecular testing equipment, both large and small. “This tiny little cube does one pharmacogenomics gene, CYP2C19,” DeFrank said. “It runs in about an hour from a buccal [cheek] swab. If a person has had a suspected stroke, you can quickly check this and know whether to put them on Plavix or on some other medication, depending on how their body metabolizes those drugs.”

Medical Laboratory Technologists Crystal Coleman (left) and Amy Hyde Beasley (right) at work with one of the high-throughput machines in the Infectious Diseases Lab.

Medical Laboratory Technologists Crystal Coleman (left) and Amy Hyde Beasley (right) at work with one of the high-throughput machines in the Infectious Diseases Lab.

Across the room, massive fully integrated real-time PCR machines can complete nearly 100 tests in a few hours. They are used for infectious diseases testing, including COVID, flu, HPV and hepatitis C. “Infectious disease tests are our highest volume,” DeFrank said.

The tests that provide the best picture of long-term treatment possibilities, on the other hand, are cancer sequencing assays, DeFrank says. Dedicated machines focused on a single gene — BRAF for melanoma and KRAS for GI cancers — can give doctors a snapshot of a tumor’s genetic makeup in about two hours. “That lets the physician start a patient on some form of chemotherapy right away while they are waiting for the larger panel of results to come back,” DeFrank said. Her lab’s largest test, an FDA-approved DNA assay for solid tumors that examines 500 separate genes at once, takes up to 10 days to get a result. “There is a lot of pipetting that goes into that,” DeFrank said.

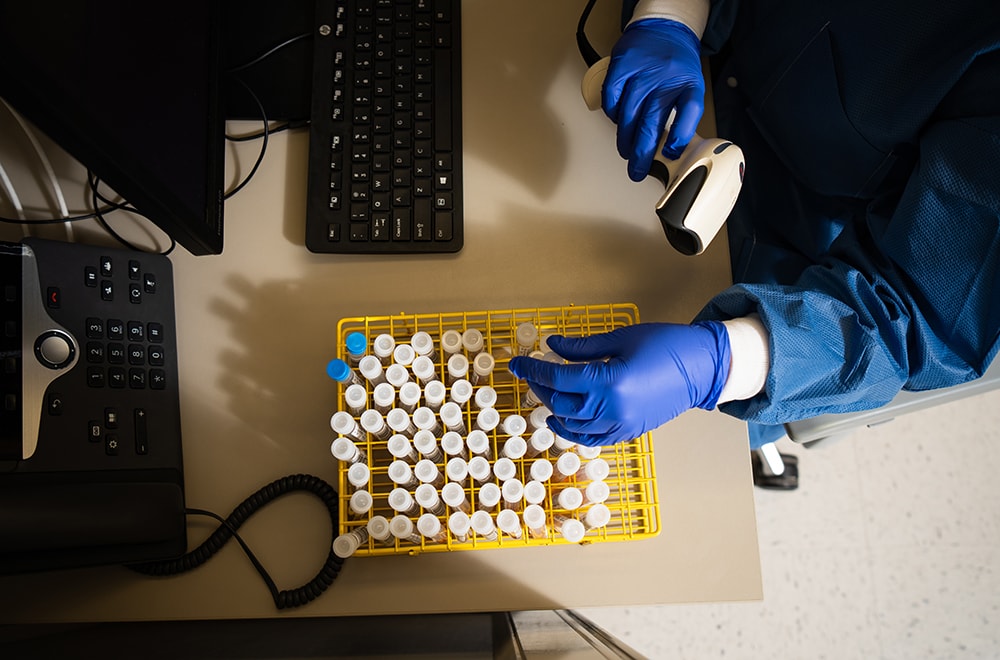

Medical Technologist Claudia Sheppard scans samples in the Infectious Diseases Laboratory.

Medical Technologist Claudia Sheppard scans samples in the Infectious Diseases Laboratory.

Once the test is finished, the work does not stop. “We work very closely with the pathologists and with the bioinformatics team, because these instruments create huge files of sequencing data that have to go into a database for storage, and they have to be put through an analysis pipeline to have those genes actually identified,” DeFrank said.

Although she is now in charge of nearly a dozen different labs, DeFrank said molecular testing is still her “first love.” When I started, “we only had three or four people and everything was manual,” she said.

There is far more automation now, which enables the technicians to handle the greatly increased volume of tests. “We would never be able to handle the volume we do now without automation,” DeFrank said. “But even as instruments are doing more, you’ve got to know if the instrument is giving you reasonable results. And with each new technology, there are always new things you have to look for; they don’t work perfectly all the time. You have to be able to spot that and not release the results. That is why our technicians will always be invaluable.”

Cellular Therapy Laboratory Supervisor Amber McKell, M.S., MLS (ASCP) with nitrogen cooling tanks used to store CAR-T cells before they are transplanted in patients.

Cellular Therapy Laboratory Supervisor Amber McKell, M.S., MLS (ASCP) with nitrogen cooling tanks used to store CAR-T cells before they are transplanted in patients.

Cell Therapy

Amber McKell, M.S., MLS (ASCP), supervisor of the Cellular Therapy Laboratory, works with some of the most intricate, and expensive, medical treatments ever devised.

The cell therapy lab handles patient cells that have been corrected in some way — faulty genes have been fixed, or previously ineffective immune cells have been trained to kill the specific cancer cells in the patient’s body. The treatments can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars per dose, but they can also be transformative for patients’ lives. “It’s just super-rewarding to be able to see the impact,” McKell said. “You are constantly reminded that what you do is very important.”

Cell therapy includes stem cells, bone marrow and cord blood, McKell explains. “The main transplants we do are from stem cells,” she said. Stem cells are used at UAB and can be modified to treat several types of cancer through chimeric antigen receptor T cells, or CAR-T, therapy. That includes multiple myeloma, leukemias and lymphomas. “We are using stem cells now more and more for other diseases, like sickle cell,” she added. UAB has been part of a clinical trial testing a potentially curative therapy for sickle cell disease.

Cell Therapy technicians Kanesha Jordan and Amanda Carpenter, M.T. (ASCP) with an automated cell processing platform

Cell Therapy technicians Kanesha Jordan and Amanda Carpenter, M.T. (ASCP) with an automated cell processing platform

The cell therapy lab’s process is similar for CAR-T cancer therapies, sickle cell therapy and other treatments. “We collect the cells and they get sent off for manufacturing,” McKell said. “Then the cells come back to us cryopreserved and we store them until the patient is ready to transplant.” Before transplant, patients “go through chemotherapy to get their immune systems wiped out, and they get the corrected cells infused back in,” McKell said. On transplant day, “we thaw the cells in the lab and take them to the patient’s bedside,” in many cases, she said.

When McKell started in the cell therapy lab in 2019, “we probably did one CAR-T stem cell transfusion per month,” she said. “Now, with more approved by the FDA, we are transplanting four or five a week.”

The best part of her job as lab supervisor, McKell says, is the combination of problem-solving and hands-on work. “I like working on the bench but also keeping things in order and making sure the staff are well trained to stay on top of the clinical trials we do,” she said. “I have to do the learning and pass on that training to others. This job involves taking in a lot of information. It’s always changing.”

McKell, a self-described “microbiology nerd,” said she “always loved labs and loved science.” After earning her bachelor’s degree in microbiology, she joined UAB’s Medical Laboratory Science master’s program. “The program experience was great — I’ve never learned so much in such a short amount of time,” McKell said. Because of her interest, McKell thought she might end up working in a microbiology lab, but “in school I fell in love with blood bank,” she said. “It’s a very hands-on area — you are actually touching the product. You are literally making a difference in whether people live or die.”

After a year or so working in the blood bank at Children’s of Alabama, McKell had the opportunity to move to the cell therapy lab. The work is just as meaningful, and it offers more chances to see the outcomes of your efforts, McKell notes. “In lots of labs, you never get to see the patients, although you know what you are doing is very important for their care,” she said. “We’re a little bit unique in that way in cell therapy, because you do get that face-to-face interaction. We might meet the patient in apheresis and then meet their family on transplant day. It’s always a really good feeling to know that you worked on their care.”

Cell Savers

Some of the team behind the life-saving Cell Savers at UAB: Left to right, Lab Supervisor Winnie Ngaruiya-Gachie, MSQHS; Director of Critical Care Laboratories Susan Butler, MSHQS, MLS (ASCP); and Anesthesia Tech Lead Isaac Parson. Photo courtesy Susan Butler.Sometimes, the best way to treat a patient with severe bleeding — whether from a gunshot, another type of traumatic injury or a scheduled surgery — is to collect that blood and give it back to the patient as quickly as possible. That’s where Cell Savers, and an Anesthesia Labs team led by Susan Butler, MSHQS, MLS (ASCP), come in.

Some of the team behind the life-saving Cell Savers at UAB: Left to right, Lab Supervisor Winnie Ngaruiya-Gachie, MSQHS; Director of Critical Care Laboratories Susan Butler, MSHQS, MLS (ASCP); and Anesthesia Tech Lead Isaac Parson. Photo courtesy Susan Butler.Sometimes, the best way to treat a patient with severe bleeding — whether from a gunshot, another type of traumatic injury or a scheduled surgery — is to collect that blood and give it back to the patient as quickly as possible. That’s where Cell Savers, and an Anesthesia Labs team led by Susan Butler, MSHQS, MLS (ASCP), come in.

“There are more and more studies showing an advantage to patients to get their own blood back,” said Butler, director for Critical Care Laboratories.

“When you are bleeding profusely, the surgeon is sucking that blood and it goes into our cell salvage machine,” Butler said. “It spins it, removes the platelets and other blood components, and keeps the red blood cells. Then it adds back saline and washes it, so you are getting a real high-hematocrit product back.”

The process is technically known as autologous cell salvage, but everyone in the hospital calls it Cell Savers. As soon as 200 milliliters of blood, about two-thirds of a typical unit, is collected and processed, technicians start returning it to the patient. “Cell Savers blood has a higher hematocrit than blood from the Blood Bank,” Butler said. “That is 40-45 and ours is 65-75.” Because it is the patient’s own blood, moreover, there is little chance that the patient will have a reaction to antibodies or other components that may be in donated blood.

“Cell Savers is also used in patients with religious objections to receiving blood from someone else,” added Winnie Ngaruiya-Gachie, MSQHS, lab supervisor for three Critical Care labs: Anesthesia, CICU and CPCC.

“Basically, any time you are losing 20 percent or more of your blood volume, we use Cell Savers,” said Anesthesia Tech Lead Isaac Parson. In 2024, Butler’s team did 2,240 cases, returning 859,286 milliliters of blood to patients and saving 2,864 packed red blood cell units from the Blood Bank.

Parson and other anesthesia technicians from Anesthesia Labs, part of Hospital Labs, do the majority of Cell Savers procedures at UAB. They operate the Cell Savers machines during all liver transplants, most traumas and many orthopedic surgery cases, including hips and spine surgeries. (Heart surgeries are particularly bloody, so the cardiovascular OR has its own dedicated teams for Cell Savers.)

“We’ve had six or seven Cell Savers going at the same time,” Parson said. Although orthopedics cases and those for patients with religious considerations are scheduled, the rest of the cases can come up at a moment’s notice. Butler and her 44 staff in Anesthesia Labs always have a team ready. “We’re staffed 24/7,” Butler said.

Few people know what they do, but Anesthesia Labs occasionally gets a moment in the limelight. “I saw one of our machines on Grey’s Anatomy one time,” Parson said. “I said, ‘There’s a Cell Savers!’ It wasn’t plugged in, though. So it couldn’t have done a lot of good like that.”

At UAB, autologous cell salvage does plenty of good. “Cell Savers saves lives,” said Sherry Polhill, MBA, associate vice president for Hospital Laboratories, Respiratory Care and Pulmonary Function Services for UAB Hospital. “It really is something.”

Preparing a new generation of lab experts

The School of Health Professions’ Medical Laboratory Science master’s program and a new undergraduate program, which will beginning enrolling students in fall 2026, train students for a career that is in demand. In 2023, the Bureau of Labor Statistics data projected that Medical Laboratory Scientist jobs will grow 7 percent nationally by 2030 and 8 percent in Alabama by 2031.

Floyd Josephat, Ed.D., program director for both graduate and undergraduate Medical Laboratory Science programs and interim chair of the Department of Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences.“There is a growing need for these roles,” said Floyd Josephat, Ed.D., program director for both Medical Laboratory Science programs and interim chair of the Department of Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences. “You can just pick a state and they have a need, which means you can work anywhere.”

Floyd Josephat, Ed.D., program director for both graduate and undergraduate Medical Laboratory Science programs and interim chair of the Department of Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences.“There is a growing need for these roles,” said Floyd Josephat, Ed.D., program director for both Medical Laboratory Science programs and interim chair of the Department of Clinical and Diagnostic Sciences. “You can just pick a state and they have a need, which means you can work anywhere.”

UAB’s program offers the only master’s-level medical laboratory science degree in Alabama and one of the few graduate-level programs in the Southeast. It is also one of the largest. At any given time, there are probably 45 to 50 students in the program, Josephat said: “That’s a lot for our profession.” Many other programs recruit less than a dozen students per class, he notes. “We are well recognized among our peers.”

Students make connections during their clinical rotations, which take them throughout UAB and to other hospitals in the area. This allows students to see the different job duties and personalities that gravitate to different areas of lab work. In the core lab areas, including Blood Bank, “you are on your feet and you have to be fast,” said Gina DeFrank, M.T., M.B. (ASCP), senior director for Lab Medicine and Genetics Labs. “There is high volume and lots of stats and people calling to check on the status of tests.” In the more specialized areas, such as microbiology or molecular, “you tend to have people who are more task-oriented, who are very detailed,” DeFrank said. “You are sitting there thinking, while something is growing, ‘What is the next test I should do to identify this sample?’ There is a lot of reasoning.”

As students learn their clinical skills, DeFrank and other lab leaders are keeping their eyes open. “We spot the good ones and we try to hire them before they graduate,” DeFrank said.

“We know they are well trained, and in many cases they have done their clinical training right here in our labs,” added Sherry Polhill, MBA, associate vice president for Hospital Laboratories, Respiratory Care and Pulmonary Function Services for UAB Hospital, who is a member of the advisory board for UAB’s Medical Laboratory Science program.

Multiple job offers are common for graduates. “They get jobs right away, and most of them stay here in Birmingham,” Josephat said. “If they want a job here, they can have it.” The program’s placement rate is 100 percent.

Another one of the program’s strongest assets is its high pass rate on the American Society for Clinical Pathology Medical Laboratory Science Certification Exam, which is required for certification and state licensure. “We prepare our students well to go out and do well in the workforce,” Josephat said. Students also are attracted to the fact that UAB’s program is accredited by the National Accrediting Agency for Clinical Laboratory Science, or NAACLS.

Most applicants to the program have a bachelor’s degree in biology, chemistry or another science field, Josephat says. Some are already working in a lab and want to get more training, or have worked in a lab. Many applicants at one time thought about going to medical school, but then realized they wanted to go into a different part of the health care workforce. “They read about our program and think, ‘I want to try this and see if medical lab science is for me,’” Josephat said. “I was one of those; I was going to apply to medical school after undergrad. Instead, I came to medical lab science, and I’ve been in it now for more than 30 years.”

UAB had an undergraduate medical technology degree program until the mid-2010s. A new bachelor’s program in medical laboratory science, directed by Josephat, was approved by the University of Alabama System Board of Trustees and the Alabama Commission on Higher Education in fall 2025. It should be enrolling students soon.

“The master’s degree is great to have because it prepares you for leadership roles,” Josephat said. “But there is also a place for staff with undergraduate training. One of the reasons we are doing it is that Sherry and several of the lab managers and directors, who make up our advisory board, are telling us they need more bachelor’s-level scientists, too.”