managing@insideuab.com

Casey Marley - Editor-in-Chief

editor@insideuab.com

UAB Sports have set the city ablaze in recent months. From the December 2014 press conference that announced the death of three sports, to the announcement of their intention to return on June 1, discussion has been rampant on the administration's next move. Efforts from students and alumni have been effective thus far, but according to UAB's new athletic director Mark Ingram, the fight is nowhere near complete.

UAB Sports have set the city ablaze in recent months. From the December 2014 press conference that announced the death of three sports, to the announcement of their intention to return on June 1, discussion has been rampant on the administration's next move. Efforts from students and alumni have been effective thus far, but according to UAB's new athletic director Mark Ingram, the fight is nowhere near complete. To understand how UAB football seemed much more feasible five months later than it did at the time of Watts' announcement, it is important to understand the difference between the initial CarrSports report and the CSS report that followed.

“We worked really hard in evaluating if we agreed with the CSS report, and how was it different from the CarrSports report. Neither report was perfect, they were more right than wrong, they were just not the same report,” said Ingram. “When you break it down they were very similar in terms of their financial findings. CarrSports included a lot of information about facilities that the CSS report didn't. So the Carr report, if you just looked at the bottom line of the spreadsheet it was a much bigger number, but when you go line by line there are big ticket items they include that CSS did not include.”

The different report gave UAB President Ray Watts the confidence to begin the process to bring back football, bowling and rifle. If the administration is asked about what changed Watts's mind, it was the money. After both reports, the school came up with a “bare minimum” number that would make Watts comfortable with beginning the process of reinstatement.

“It all comes back to the amount of financial support that we got that we had never had before,” said Ingram. “What's the big difference between June and December? $17.2 million.”

The efforts of organizations like the Birmingham City Council and private fundraiser closed that 17 million dollar gap, but the work must continue.

“We have not completed our fundraising needs. It is critically important that we continue to grow in that area,” said Ingram. “Money was raised to a certain point that allowed the President to make a decision on all this. That doesn't make us wealthy.”

The city of Birmingham stood up behind UAB and gave tangible proof of its commitment to the future of this school's athletics. As UAB fights to stay on the field and hardwood, it is important to remember that this city has seen UAB triumph before, and is witnessing its triumph every day.

The school's time as a member of the UA system has been a story of not always having the final say in its future. In order to understand what has been a constantly shifting horizon for UAB, it may be prudent to start by looking in the rearview mirror to gain a sense of UAB's history.

UAB was not always UAB. The 88 square blocks that comprise this southern urban campus were not always adorned with the green block letters seen on hospitals and pedestrian bridges scattered on University Boulevard. UAB's rise to an autonomous tier 1 research institution within the University of Alabama system began in the late 19th century.

A complete history of UAB is not hard to find, UAB Archives has posted “A Chronological History of the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and its Predecessor Institutions and Organizations, 1831-” —a timeline of UAB’s history to present day.

According to the Board of Trustees supplied dates, nothing UA related existed in Birmingham until 1912, when the trustees of the Birmingham Medical, Dental and Pharmaceutical Colleges transferred ownership to the University of Alabama B.o.T.

In 1915, the Birmingham Medical College graduated its last class before “the program was terminated by The University of Alabama Board of Trustees,” the timeline said.

Fast-forward five years to April 1920. A medical school in Alabama was still needed, and the “Alabama Medical School,” a two-year pre-clinical school was ordered to move from Mobile to Tuscaloosa. In 1936, UA’s influence returned to Birmingham when it opened the “Birmingham Extension Center” in “an old house” at 2131 6th Avenue North. The extension of the “Capstone” campus in Tuscaloosa taught 116 students in its first year.

When an Act that granted $1.3 million to the expansion of UA’s medical school, moved to Tuscaloosa, passed in 1943, UA chose Birmingham to be the home of the new four-year medical school the following year. In 1945, the Medical School opened its doors in Jefferson County.

With a new medical school in hand, 1946 proved to be the year that the “extension center” outgrew its “old house” in Northside. With over 500 students, UA leased space in Phillips High School to make space for its growing student population. 11 years later, the extended campus grew to 1,856 students, and in 1959 the Birmingham based Medical School was awarded over $1 million in research and training grants and fellowships.

In the 1960’s UA’s commuter extension center began to come into its own. In 1966, the Extension Center’s status was raised to a four-year “College of General Studies”, and in November of that year, all University operations in Birmingham were newly minted with the name “University of Alabama in Birmingham”—but was still considered a branch of UA in Tuscaloosa.

However, in the same year man landed on the moon, change occurred for the UA system as well. On June 5, 1969 the B.o.T approved a plan to create three separate Universities within a system, each with their own president “that would report to the Board of Trustees.” In the next weeks, the UA System was born, its members: the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Birmingham and Huntsville.

Throughout UAB's ascendance, the Board of Trustees has been an ever-present force in the background, making many decisions that would have ripples felt up until the present day. But to understand the

The University of Alabama system Board of Trustees began with a domain that was more limited than the one to which they are entrusted in this day and age.

According to James Benson Sellers' “History of the University of Alabama Volume One 1818- 1902,” the B.o.T. was formed in 1820, a decade before the University began to admit its first students. When the members of the board were elected on December 19, 1821, they were allotted three dollars for every day that they actually did work on the University's issues, and an extra three dollars for every 25 miles that they had to travel going to and coming from meetings.

This small stipend may seem inconsequential, but the board's behavior after receiving this small sum is perhaps indicative of the board's mindset. As Sellers states, “When the University was organized and professors appointed, these allowances were to stop. It is interesting to note that when the time for discontinuing the payments came, the trustees conveniently forgot this stipulation.”

That board's actions fit the pattern for their stewardship of the University of Alabama system, of which the University of Alabama has been a member since the system's foundation in 1969.

Dr. John D. Volker, former UAB president, became the chancellor of the three-school UA system, and served as the system leader until 1983. That same year, the B.o.T.'s modern pattern of resistance began in earnest around the time that Lieutenant Governor Bill Baxley began placing members on the BOT. Baxley, an avowed fan of the Crimson Tide, was the actor in many moves that disenfranchised UAB on the Board of Trustees, one of which in particular may be traced to UAB's current troubles.

In 1983, Baxley appointed Frank Bromberg to the Board of Trustees. In 2001, Bromberg would retire in the midst of a heated controversy in order to allow the ascension of Paul Bryant, Jr. Son of Paul “Bear” Bryant, and head of Bryant Bank. People with ties to Bryant Bank make up the majority of the Board, and they tend to vote in the direction of the son of the Bear, according to an AL.com column written in March.

In 1997, less than a year after being hired as the dean for UAB's School of Business, Albert Niemi retired from the position to take the same job at Southern Methodist University. Niemi left the post despite being made one of the highest paid employees in the state at the time with a $290,000 salary.

In his final address to the faculty which was reprinted in an April issue of the Kaleidoscope, Niemi laid bare several issues that he had with the B.o.T. of the time.

"I've never seen anything like it. The loyalty to Tuscaloosa and the protectionist attitude the trustees have about it is something I've never seen," Niemi said."What I see is they worry more about this institution than we do about them. Until that institution embraces and wishes UAB well, and until the trustees grab hold of that and wish UAB well, then UAB cannot move forward.”

Despite Niemi's warning, and assertion that the board's makeup at the time was unsustainable (fourteen people with ties to UA and only one UAB representative, none for UAH), his calls for equal representation on the board went unheralded.

Strangely enough, Niemi's peer in the Tuscaloosa position did not report the same amount of resistance. Barry Mason, the dean of UA's business school at the time, had his rebuttal printed in the very next issue of UAB's Kaleidoscope that year.

In regards to alleged favoritism by the Board of Trustees, Mason stated, “I have never seen it. The Chancellor's office has the primary responsibility for ensuring fairness and equity in the treatment of all three campuses and I don't think they are partial to either of the campuses.”

Incidentally, Mason also had an opinion on the makeup of the Board of Trustees at the time.

“The makeup of the board is very balanced geographically, Every section of the state is represented,” said Mason. “I feel that it is in the best interest of the board to have the most qualified individuals present, not necessarily five from Tuscaloosa, Huntsville and Birmingham.”

Mason must have foreseen the board's best interest continuing unaltered into the present day, where twelve members are UA graduates,

The board has made some interesting decisions in the time since Mason stood up for its composition.

In 2006, UAB was in need of a new football coach. The search took a while, but it was finally settled when UAB administration decided on a coach named Jimbo Fisher. Fisher had a history of proven division one football success. He had spent seven years as offensive coordinator at LSU, five of which took place under Nick Saban, and he was ready for a change.

According to an article from AL.com, Fisher had agreed to a two-year, $600,000 contract and was hired in everyone's imagination, until the Board of Trustees sent down the message that Fisher could not be hired. Citing fiscal responsibility, the B.o.T. did not give the go ahead.

Coincidentally, the B.o.T. signed Nick Saban to an eight-year, $32 million dollar contract as soon as the Miami Dolphins finished their 2006 season, according to ESPN.com. Due to the move that blocked Fisher from signing with UAB, he was free to join Saban if he so desired in Tuscaloosa.

However, instead of playing into the B.o.T.'s plan and reuniting parts of a former championship coaching staff, Fisher chose to take a job under Bobby Bowden at Florida State. After Bowden retired two years later, Fisher took over and eventually led FSU to an overall record of 58-11, three ACC titles, the inaugural college football playoffs and the 2013 national championship.

According to an article from AL.com from January of 2014, Fisher gave his perspective on the UAB situation at media day before the 2013 BCS National Championship.

"Somebody made a decision," said Fisher. "It's funny in this business. You coulda went here. You coulda went there.”

"Luckily, I'm glad they made that decision."

This would not be the last time football became a battleground for the Board of Trustees.

In 2011, the B.o.T. blocked UAB's plans of building a brand-new football stadium on its campus.

“A majority of the Board believes that an on-campus football stadium is not in the best interest of UAB, the University System or the State," said the BOT in an official statement. "It is the Board's duty to be responsible stewards of the limited resources available for higher education. In these difficult economic times of rising tuition and decreasing state funds, we cannot justify the expenditure of $75 million in borrowed money for an athletic stadium which would only be used a few days each year. The UAB football program has not generated sufficient student, fan or financial support to assure the viability of this project."

After denying the Blazers a $75 million dollar stadium, on the grounds that it was not fiscally responsible, the very next year the Board of Trustees approved a new contract for Nick Saban that would pay the Tide coach $45 million dollars over an eight-year period.

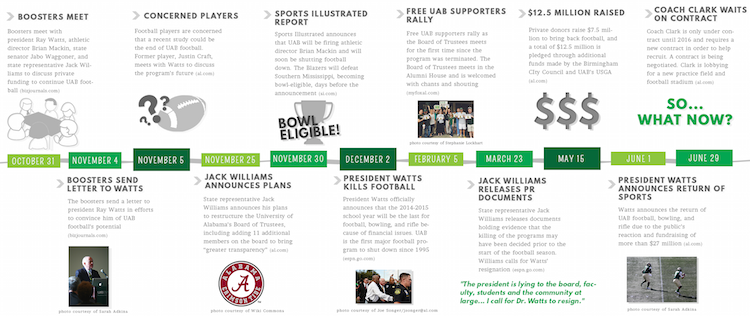

For a look at UAB’s recent history for the past year, view the timeline below.

Chart by Jessica Middleton

Chart by Jessica Middleton