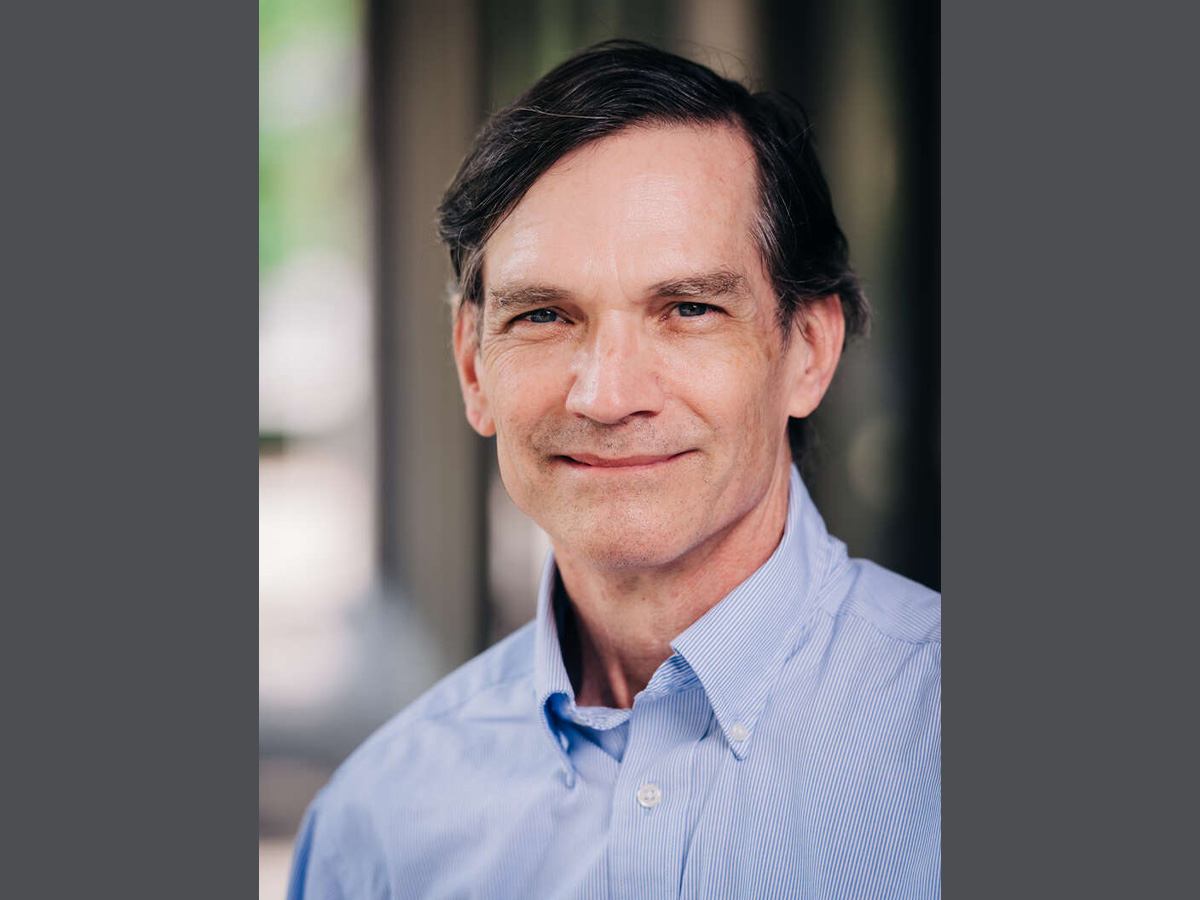

Lauren Lake: "swath 21," mixed media on paper, 13.5" x 13.5", 2017College of Arts and Sciences researchers investigate what actually happens when we age—from our cells to our cognition—in the hopes of prolonging high-quality life.

Lauren Lake: "swath 21," mixed media on paper, 13.5" x 13.5", 2017College of Arts and Sciences researchers investigate what actually happens when we age—from our cells to our cognition—in the hopes of prolonging high-quality life.

By Cary Estes

Artwork by Department of Art and Art History faculty members: Doug Baulos, Gary Chapman, Stacey Holloway and Lauren Lake.

An Orchestra of Genes

Imagine attending a symphony concert where the conductor suddenly walks off stage in mid-performance. The musicians likely would be able to continue in synch on their own for a short period of time. But without a central person to maintain rhythm and control, the music would become increasingly chaotic until all semblance of a coherent melody falls apart and eventually stops completely.

That, in essence, is what happens to our bodies from a physical standpoint as we age, according to Steven Austad, Ph.D., distinguished professor and chair of the Department of Biology. Austad says there is a “symphony of gene expression” taking place within our bodies, with genes being turned on and off at the appropriate moments. But the timing and organization of this genetic activity tends to fade with age, resulting in a gradual physical deterioration.

“It’s a process that happens to virtually everything, but it happens at vastly different rates,” Austad says. “So a dog gets old in 10 years, while for a human it takes 80 years. One of the big mysteries is figuring out exactly why that’s going on.”

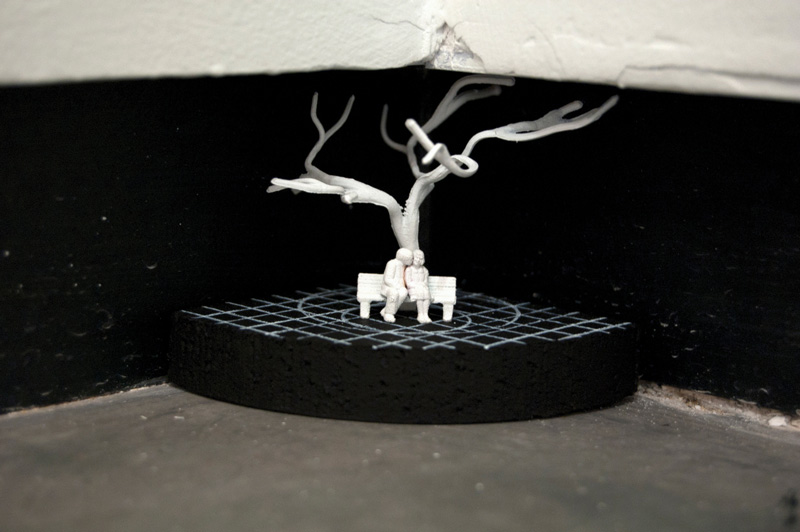

Stacey Holloway: "Secrets," mixed media, 2.5” x 2” x 2”, 2014Along with Kathleen Fischer, Ph.D — a research assistant professor in the Department of Biology — and several other UAB collaborators, Austad is conducting extensive studies into the physical process of aging. In 2015, Austad was named the director of UAB’s Nathan Shock Center of Excellence in the Basic Biology of Aging, one of only six such centers across the U.S. funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Stacey Holloway: "Secrets," mixed media, 2.5” x 2” x 2”, 2014Along with Kathleen Fischer, Ph.D — a research assistant professor in the Department of Biology — and several other UAB collaborators, Austad is conducting extensive studies into the physical process of aging. In 2015, Austad was named the director of UAB’s Nathan Shock Center of Excellence in the Basic Biology of Aging, one of only six such centers across the U.S. funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Part of Austad’s and Fischer’s research involves trying to decipher why there is such a wide disparity in the lifespan of different animals. There are some vertebrae fish that live less than 6 months, while the quahog clam can live for 500 years.

“We use these differences in longevity to try to get at the relationship between the rate of aging, and an animal’s energy acquisition, storage and use,” Fischer says. “Are the animals that live longer better at protecting proteins from aggregation, which is one of the problems that organisms suffer as they get older? Proteins have to be a certain shape to function. If they get stuck together and aggregated, they can’t function properly. So the quahog, for example, is really good at maintaining protein function and keeping them from becoming aggregated over hundreds of years. We’re trying to understand what it is about metabolism that influences aging.”

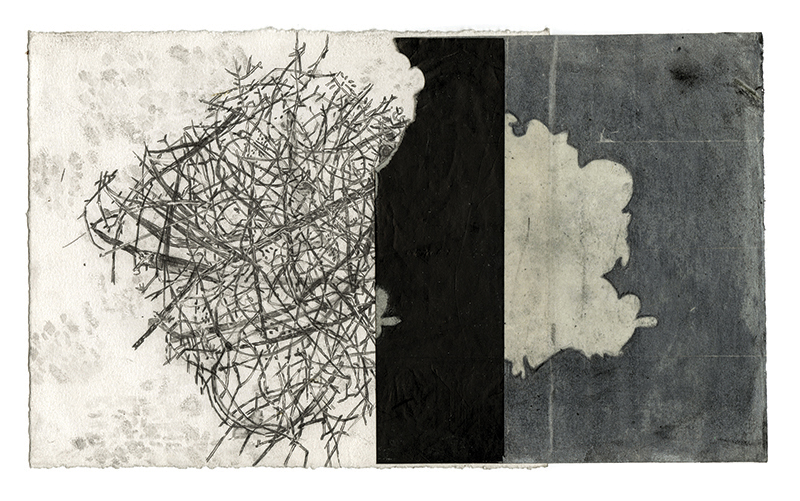

Doug Baulos, "Binding my Lost Heaven" exhibition, 2015. Another area of research involves the aging differences between men and women. While women worldwide generally live longer than men, they also tend to have more physical problems in older age than men do. “That’s a paradox that nobody really understands yet,” Austad says. “We’re just beginning a series of studies to try to understand those differences. That’s a major focus of our research right now.”

Doug Baulos, "Binding my Lost Heaven" exhibition, 2015. Another area of research involves the aging differences between men and women. While women worldwide generally live longer than men, they also tend to have more physical problems in older age than men do. “That’s a paradox that nobody really understands yet,” Austad says. “We’re just beginning a series of studies to try to understand those differences. That’s a major focus of our research right now.”

Fischer says one possibility might be found in the basic hormonal distinction between men and women. She points out that hormones in women decline dramatically during menopause, whereas with men the decline is more gradual.

“That’s one of the ways we can start to take apart what’s going on with the biology of aging to try to understand the mechanisms that underlie these age-related changes,” Fischer says. “Once we do that, we can try to figure out how we can intervene in order to prevent this decline in health with age.”

The goal of this research is not necessarily to prolong human life, but rather to improve the quality of life as we age. Austad says it is possible that with enough scientific discoveries in this field, people eventually could take daily medications – much like baby aspirin is currently used to help prevent heart attacks – that would literally slow down their rate of physical aging.

“So by the time a person gets to age 80, they would be the physical equivalent of someone several decades younger. That’s sort of the ultimate goal,” Austad says. “The idea isn’t to make people live longer. It’s to keep people functioning longer. If you can have the same ability at 80 years old to walk and hear and go upstairs and do what you want, that’s the kind of advance we’re looking for. If we can affect the underlying process of aging, then we can delay all these problems.”

Collaborators with

Dr. Stephen Austad

Dr. Stephen WattsProfessor

Department of Biology

“It has been a pleasure to work with Dr. Austad in his projects related to comparative aging. Working together, we are examining the nutritional basis of health in a variety of animal models. It is apparent that many nutrients or nutrient combinations can affect disease onset and progression, and our studies can potentially lead to a better understanding of the role of nutrition in healthy aging and an associated extension of health span for human beings.”

Exercise for the Mind

A certain level of physical decline will inevitably happen to all of us. A person who is a great athlete in their 20s and 30s simply will not have the same strength and stamina later in life, no matter how much they work out. Father Time, as they say in the world of sports, is undefeated.

Mental abilities, however, do not always diminish with age. There are people who remain mentally sharp well into their 80s and even 90s, while others begin having basic cognitive issues such as forgetfulness in middle age. Some of the decline is disease related, but for many people it is just a consequence of getting older. “Senior moments,” they are called. Yet these types of memory lapses never arrive for some seniors.

“There is very little variability in many of these abilities when you’re younger. Everybody is doing pretty well,” Ball says. “As people age, though, the variability gets higher. You have some people who aren’t much worse than they were when they were young, and then others who have a steady decline. What we are asking is, ‘What did those people do when they were younger that might have prevented any decline from occurring? And what can we do now to mentally stimulate those cognitive abilities in order for people to regain them?’”

Ball and fellow researchers at UAB have been conducting studies looking at cognitive training programs, which she said are “basically ways to exercise the brain.” They have run tests to see how quickly a person can handle such common functions as looking up a phone number, making change for a dollar, or finding a specific food item on a crowded grocery store shelf.

“We’ve looked at not only their performance on the cognitive tests themselves, but how does this translate into improvements in their everyday life,” Ball says. “In addition, we also look at what changes in the brain before and after they go through these exercises, and see where in the brain these changes are occurring.

“What we’ve found over the years is you can improve an older person’s cognitive abilities by doing targeted exercises that get progressively more difficult as they improve their performance. And the changes that occur in their cognitive skills translate to improvements in everyday function.”

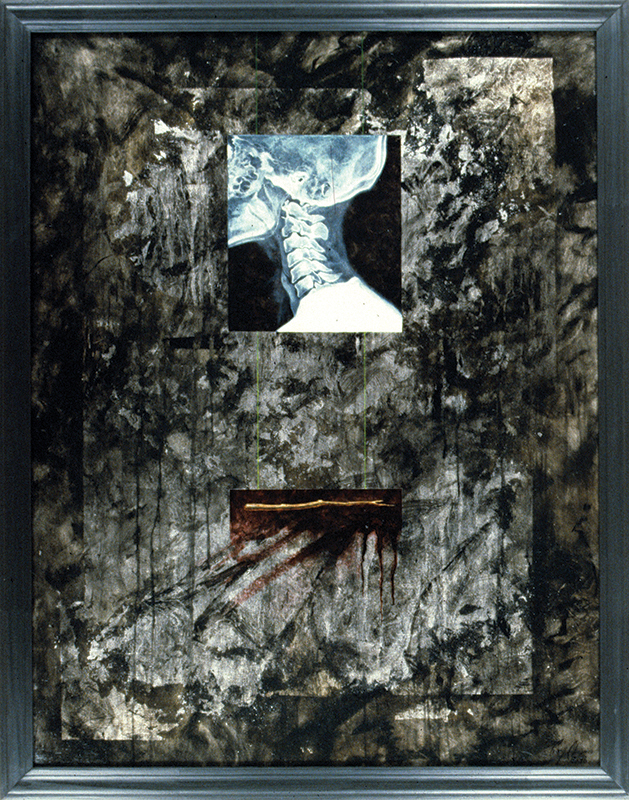

Gary Chapman, "INSIGHT," oil/silver leaf on linen, 53h x 42w, 1996. Ball also has been involved in studies examining cognitive issues in the ability to drive a car. Ball says this research is particularly important because many seniors feel isolated or have to enter an assisted-living facility once they no longer are able to drive.

Gary Chapman, "INSIGHT," oil/silver leaf on linen, 53h x 42w, 1996. Ball also has been involved in studies examining cognitive issues in the ability to drive a car. Ball says this research is particularly important because many seniors feel isolated or have to enter an assisted-living facility once they no longer are able to drive.

“We have found in a large clinical trial that if certain people go through the cognitive training program, they were half as likely to crash over the subsequent seven years, with benefits to some extending as far as 10 years,” Ball says. “So whatever we’re doing with the cognitive training seems to have a long-term benefit.”

Ball says researchers are now trying to discover exactly how widespread these types of training programs can be applied, ranging from patients with mild cognitive impairments to those with more severe diseases such as Parkinson’s. She says they also are looking at how much physical exercise and creative activities like knitting can improve cognitive abilities.

These studies are being conducted in collaboration with several other researchers at UAB, including Virginia Wadley Bradley, Ph.D., in the School of Medicine; Karen Meneses, Ph.D., RN, FAAN, in the School of Nursing; and Cynthia Owsley, Ph.D., MSPH, in the Department of Ophthalmology (see sidebar at right).

“One of the things that’s been great at UAB is the opportunities for collaboration across the whole campus,” Ball says. “We’ve provided these kinds of training programs to many other researchers, so they can try it out in their particular areas of expertise. So what’s really promoted this research is our ability to collaborate internally across campus as well as externally.”

Collaborators with Dr. Karlene Ball

Dr. Virginia Bradley

Professor of Gerontology,

Geriatrics and Palliative Care

School of Medicine

Dr. Cynthia Owsley

Professor of Ophthalmology

School of Medicine

“Dr. Ball has been part of our research team here in the Department of Ophthalmology, where we have conducted a NIH-funded population-based study on 2,000 older drivers in Alabama. The goal of the study is to examine which vision screening tests are related to collision involvement three years after the screening. Vision screening tests currently used at the state licensing office do not identify drivers at increased risk for collision involvement. So our study will be very useful for advising states on driver’s licensing policy. Preliminary analysis of the data suggests that tests of peripheral vision and slowed visual-processing speed had the highest sensitivity for identifying older drivers who would be involved in future crashes.”

Dr. Karen Meneses

Professor and Associate Dean for Research

School of Nursing

“I am currently a recipient of a pilot funding from Dr. Ball’s Center for Translational Research on Aging and Mobility. My project is called Speed of Processing in Middle Aged and Older Breast Cancer Survivors (SOAR)., which determines the cognitive changes that occur in cancer survivors as they return to work and live full lives. The pilot is important because cancer survivors are living longer, and the intervention may help them live better. Funding for this project has also enabled me to include my predoctoral students in the recruitment, retention, testing, and support for the intervention.”