After a devastating car accident, Garry Taylor, 71, had nearly a zero percent chance of survival. Pre-hospital blood extended his survival to allow him to get the lifesaving care he needed at UAB Hospital.

On the morning of Oct. 15, 2024, Garry Taylor, 71, was in Cullman, Alabama, on his way to add to his classic rock vinyl record collection. A devastating accident left him clinging to life, and he was airlifted to University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital with injuries that left him with a nearly zero percent chance of survival.

That morning, as he was driving down the highway, another vehicle broadsided him flipping his truck and inflicting extensive traumatic injuries. Just as he arrived in the UAB trauma bay, Taylor lost his pulse.

In a lifesaving effort, the trauma team performed a resuscitative thoracotomy right in the trauma bay, opening Taylor’s chest to clamp the aorta and redirect blood flow to the heart. They also carried out a splenectomy to remove the damaged spleen and treated multiple bowel injuries along with extensive internal bleeding.

“The first night Mr. Taylor was at UAB, it took around-the-clock care and resuscitation to try to stabilize him,” said Daniel Cox, M.D., UAB trauma medical director and the surgeon who cared for Taylor when he arrived to UAB Hospital. “At that time, we did not know if he would have a good functional outcome. Patients his age who lose a pulse from severe blunt trauma prior to arrival to the hospital essentially have a zero percent survival rate. Fortunately for Mr. Taylor, the pre-hospital blood he received extended the clock on his survival and kept his heart beating right to the point of reaching the hospital, and that gave us the fighting chance to save him.”

More than 50 miles away from UAB Hospital, an American College of Surgeons-verified Level 1 Trauma Center, first responders had to act quickly to keep Taylor alive. At the scene, they administered pre-hospital blood.

Pre-hospital blood involves the administration of blood products by EMS clinicians to patients who have experienced severe bleeding at the scene of injury or en route to medical care. Taylor is one of thousands of patients a year who are saved by pre-hospital blood.

“If a patient makes it to UAB with a pulse, their survival rate is about 97 percent,” Cox said. “Pre-hospital blood kept Mr. Taylor alive just long enough for him to make it to us. He would have gone into cardiac arrest sooner without pre-hospital blood, and we would not have been able to bring him back. It helped him keep a pulse and maintained his blood pressure right up to the point of reaching the hospital. This allowed us the time we needed to do blood transfusions and surgeries as soon as he made it to us.”

Severe bleeding is the leading cause of preventable deaths

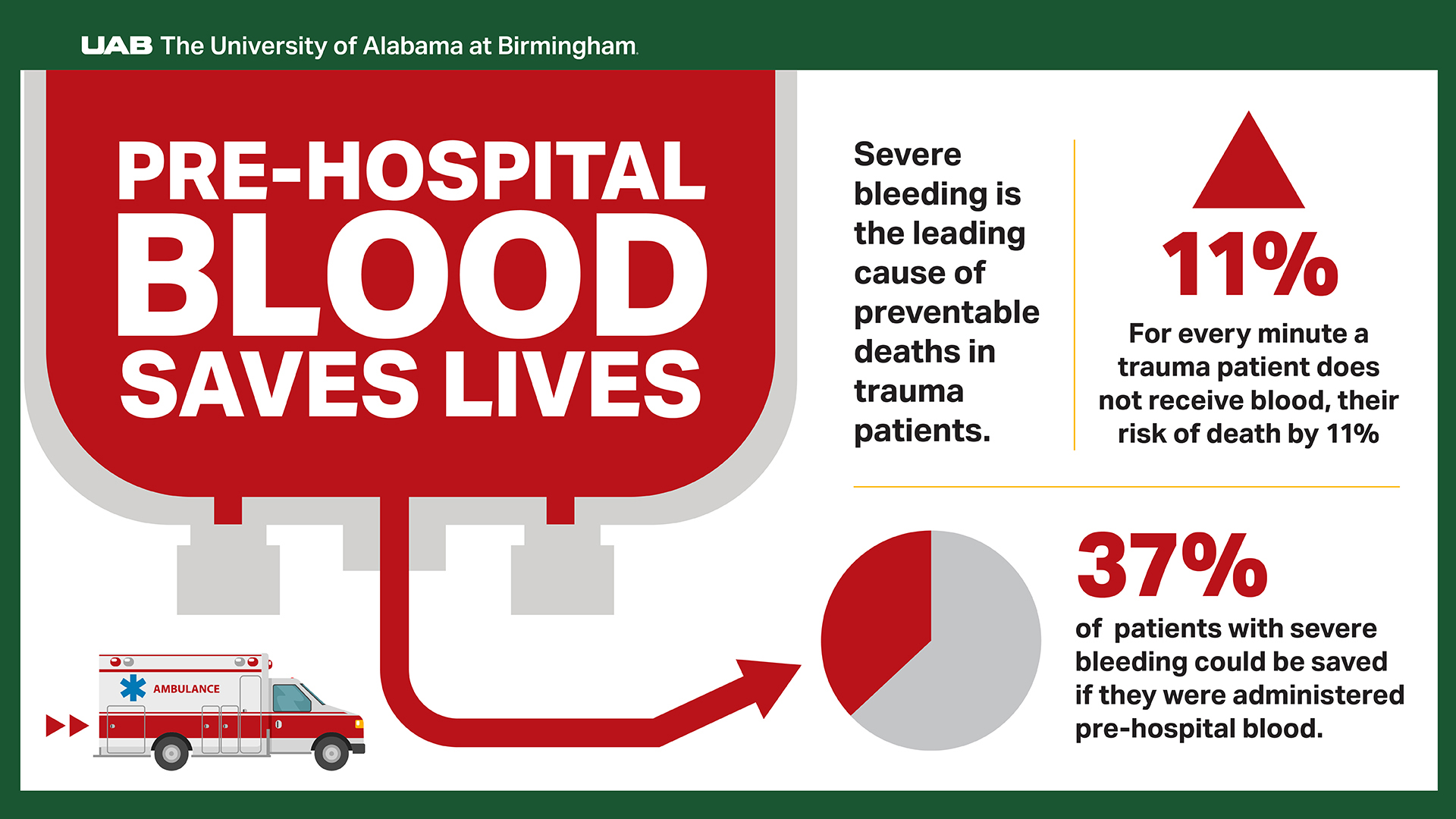

Severe bleeding is the leading cause of preventable deaths in trauma patients, including those involved in multi-vehicle crashes. For every minute a patient with severe bleeding does not receive a blood transfusion, their risk of death increases by 11 percent, according to EMS.gov.

An estimated 37 percent of trauma patients with severe bleeding could be saved if they were administered pre-hospital blood. However, while there is data showing that trauma patients like Taylor who received pre-hospital blood were four times more likely to survive than those who did not, it is severely underutilized across the nation, particularly in rural areas where it is needed most.

Fewer than 3 percent of ambulance agencies nationwide carry blood products.

“While many people understand that health care providers administer blood to patients in the hospital, most do not know that we rarely administer blood before they get to the hospital,” said John Holcomb, M.D., a professor in the UAB Division of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. “Most people think that, when you get on an ambulance and you are hurt bad, you are going to receive blood because you are bleeding. However, in 97 percent of ground ambulances, you are receiving only crystalloids.”

Crystalloids, which are IV fluids made of mineral salts, are commonly used for pre-hospital resuscitation. A study involving Holcomb found they can impair oxygen delivery, hinder blood clotting and raise the risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome.

“The bottom line is that pre-hospital blood saves lives.”

“The bottom line is that pre-hospital blood saves lives,” said Jeff Kerby, M.D., a trauma surgeon and the director of the Division of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. “We always say that where you live should not determine if you live. When EMS agencies can provide lifesaving care by administering resuscitation, primarily in the form of blood products, the patient has a better chance of survival than if they do not receive that blood product. In cases where there is a long transport, it can be lifesaving.”

Kerby emphasizes that many people, especially in rural America, live in a trauma desert. Taylor is one of the estimated 60 percent of Alabamians who live about an hour away from a Level I and Level II trauma center, which has the highest capabilities and resources available to treat trauma. However, trauma deserts are not just a concern in Alabama. Nationwide, an estimated 30 million to 40 million Americans live more than an hour away from high-level trauma care. This further indicates a need for blood products to be administered by pre-hospital clinicians at the scene of the injury.

“When you live more than an hour away from a trauma center, being able to survive that long transport so we can have the opportunity to intervene is very important,” Kerby said. “Blood is a very important part of that equation. We need to have more of our EMS agencies across the country carry blood to hopefully extend the window of survival that a patient has from the point of injury to their getting to definitive care. Certainly, blood products can extend that window of survival.”

Barriers to pre-hospital blood

EMS agencies are currently reimbursed for transportation, not for the medical care they provide. As a result, many cannot afford to carry whole blood due to the high costs of storage and transport — and the lack of reimbursement for administering it.

Keeping the blood supply up to where EMS agencies have the supply they need to store on their vehicles is another challenge.

A large blood supply is needed to help trauma patients in a pre-hospital setting, as well as help other populations of patients get the blood products they need for their care. To help address the nationwide blood shortage, UAB partners with the Red Cross to host a blood donation center at the hospital and multiple blood drives across campus.

“The opportunities to save 40,000 or 50,000 lives every year is right there in front of us,” Holcomb said. “We don’t need to invent a new drug. We don’t need to have the FDA approve it. It’s right there. People just need to donate and then we need to use it.”

Mission to save more lives

By addressing these barriers, UAB trauma experts hope many others like Taylor can continue to be saved. Today, more than a year after his accident, Taylor reflects on all he has accomplished during his recovery.

“It blew my mind to see pictures of the accident,” Taylor said. “People say ‘I do not know how anyone survived it,’ and I don’t see how anyone survived it either; but I have, and I am thankful to all the doctors, nurses and first responders who helped me survive it.”

One of the goals that motivated Taylor during his recovery was his desire to get back to his position of conducting the Cullman Community Band — something he has done since 2010. Taylor has been back at the rehearsals since January 2025 and is currently preparing for their upcoming concerts.

“The first day back with the band was very emotional for me. They were so happy to see me and happy to see that I was recovering. The thought of all of that love toward me was overwhelming,” Taylor said. “This accident has brought into focus the second opportunity I have now. I went through this accident, and I am coming back like I was before. How many people can say that? Not that many. I thank the trauma team and all those doctors and nurses who made that possible.”

Holcomb says anyone can help propel the mission of getting pre-hospital blood on ambulances across the country.

“You can donate blood,” Holcomb said. “You can call your local EMS agency and ask if they have blood. If they do, congratulate them because it’s taken a lot of work for them to do that. If they don’t, ask them how you can help them get blood on hand. You can get involved with the pre-hospital blood coalition. That’s what the local person could do at every level.”