|

Gorgas Case 2014-10 |

|

| The Gorgas Courses in Clinical Tropical Medicine are given at the Tropical Medicine Institute at Cayetano Heredia University in Lima, Perú. Each August we conduct one of our 2-week refresher courses for those with previous training in tropical medicine; currently in session is the Gorgas Expert Course. For the past 14 years, we have been pleased to share interesting cases seen by the participants each week when our courses are in session; there will be one more case next week to complete the 2014 case series. Each case includes a brief history and pertinent digital images, followed by a link to the actual diagnosis and a brief discussion. |

| The following patient was seen by the Gorgas Expert Course participants in the outpatient department of the 450-bed Cayetano Heredia National Hospital in Lima. |

|

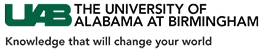

Epidemiology: Born and lives in Santa Cruz, Cajamarca (2500 meters above sea level). Works as a schoolteacher in a community located two hours from Santa Cruz. Denies agricultural activities, but does work in his home garden, no direct animal contact. There are cattle at his place of work. Physical Examination: Afebrile. Papule with desquamating borders on the fourth finger of the right hand and nodular lesions following two lymphatic branches up his right arm beyond the elbow [Images A, B]. No axillary lymphadenopathy. No hepatosplenomegaly. Laboratory Examination: Hb 15.8 mg/dl, WBC 8.2 with normal differential, glucose 92. Bacterial cultures of a nodule aspirate were negative. |

| Diagnosis: Sporotrichosis due to Sporotrix schenkii. |

|

The differential diagnosis of nodular or ulcerated lesions in Perú with or without lymphocutaneous spread includes leishmaniasis, sporotrichosis, atypical mycobacteria, and nocardiosis. Sporotrichosis is always an important consideration in areas such as Perú even where leishmaniasis is much more common. In normal hosts, linear sporotrichoid lesions on an extremity would be the most common presentation of sporotrichosis [see Gorgas Case 2008-01]. In normal hosts, extracutaneous manifestations of sporotrichosis include osteoarticular, meningeal, and pulmonary sporotrichosis. These are usually seen in immunocompromised hosts and in alcoholics. In the last two decades a systemic presentation restricted almost exclusively to HIV patients has been described [see Gorgas Case 2011-02 and Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2011;5(1):42-8]. Environmental reservoirs for S. schenkii include sphagnum moss (including wood or plants contaminated by moss), decaying vegetation, hay, soil and masonry. Outdoor work including farming, construction, gardening, and having a cat are risk factors [Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(4):529-35 and Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(1):34-9]. Acquisition is generally by local inoculation. Sporotrichosis is distributed worldwide but most cases are reported from the Americas and Japan. Most cases are sporadic or occur in self-limited clusters due to some point source exposure. The area around Abancay, Perú (not where this patient lives) has recently been, perhaps uniquely, identified as an area where sporotrichosis is not only entrenched but is hyperendemic with annual incidence rates of up to 60 per 100,000 population [Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(1):34-9 and Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(1):65-70]. Guidelines for treatment of sporotrichosis have been released by the Infectious Diseases Society of America [Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(10):1255-65] and are partly based on work from our Institute. The treatment of choice for lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis is itraconazole, and in severe extracutaneous or disseminated disease amphotericin B can be used. Terbinafine 500-1000 mg po bid has been shown to be effective therapy [Mycoses. 2004;47(1-2):62-8]. Posaconazole is the only newer azole to have good in vitro activity against S. schenckii. Fluconazole at higher doses (400-800 mg daily) has demonstrated some activity for lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis, but voriconazole, ravuconazole and the echinocandins are ineffective against S. schenckii though some are active against other Sporothrix species. In the reality of poor countries, many patients cannot afford itraconazole or terbinafine. The older but still effective mode of therapy with a saturated solution of potassium iodide (SSKI) is still widely used in practice. SSKI and its clinical use has been reviewed [J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(4):691-7] and we have previously demonstrated the utility of once daily dosing in order to increase compliance [Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15(4):352-4]. The mechanism of action is unknown. SSKI can also be used for entomophthoromycosis caused by Basidiobolus and Conidiobolus. In dermatologic practice SSKI can be used for erythema nodosum, nodular vasculitis, erythema multiforme, and Sweet’s disease. The main adverse effects are gastrointestinal (nausea) and the SSKI can be added to larger volumes of water, juice, or milk for administration. Care must be taken to avoid potassium or iodide toxicity in patients on ACE inhibitors or potassium sparing diuretics, in patients with renal disease, and in patients on medications or with conditions making them unable to autoregulate thyroid hormone production. In areas with high rates of iodine deficiency, such as the Andean highlands, the use of this solution can trigger hyperthyroidism (Jod-Basedow disease). This patient was started on itraconazole 200mg/day with a plan for at least 3 months of treatment. |

History: 49 yo male with a 2-month history of pruritic painless papules, nodules and then ulcers on the right arm. He noticed the first papular lesion on the fourth finger of the right hand and one week later he noticed multiple nodular lesions extending up the forearm and beyond the elbow. He denies constitutional symptoms or known trauma to the hand. He was diagnosed locally with cutaneous leishmaniasis based on a scraping of the ulcer and was treated with sodium stibogluconate 20mg/kg intravenously for 20 days, noticing some improvement of the lesions. However, few days after completion of treatment he observed worsening of the lesions and appearance of new lesions.

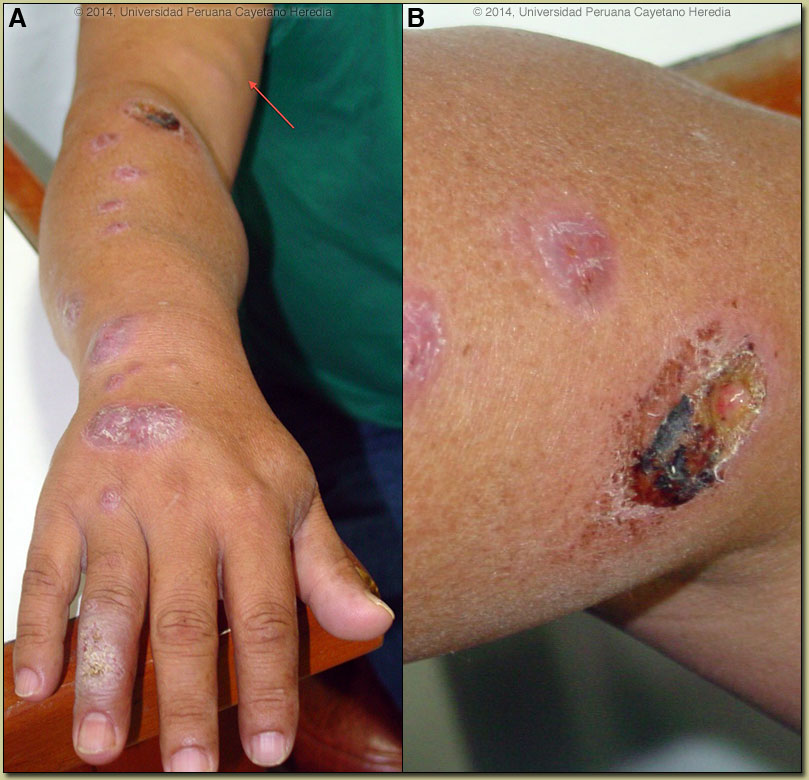

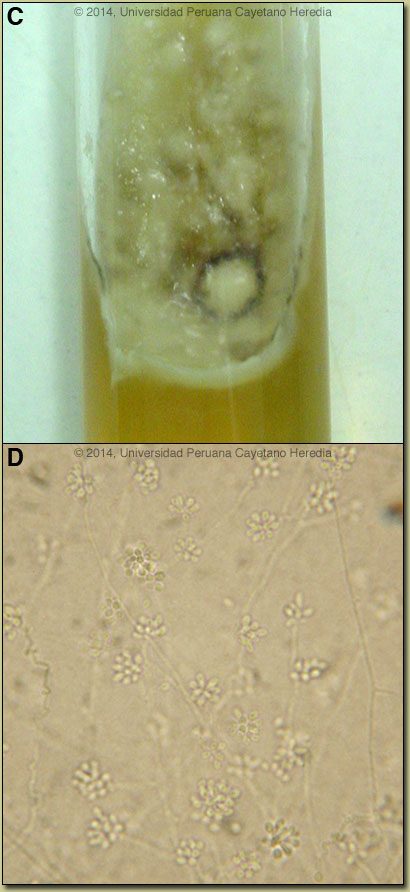

History: 49 yo male with a 2-month history of pruritic painless papules, nodules and then ulcers on the right arm. He noticed the first papular lesion on the fourth finger of the right hand and one week later he noticed multiple nodular lesions extending up the forearm and beyond the elbow. He denies constitutional symptoms or known trauma to the hand. He was diagnosed locally with cutaneous leishmaniasis based on a scraping of the ulcer and was treated with sodium stibogluconate 20mg/kg intravenously for 20 days, noticing some improvement of the lesions. However, few days after completion of treatment he observed worsening of the lesions and appearance of new lesions. Discussion: Sporothrix schenkii was cultured [Images C, D] from an aspirate from the border of an ulcer, the best place to sample for both sporotrichosis and leishmaniasis. In culture of scrapings, aspirates or biopsy material on Sabouraud’s agar, S. schenkii grows very easily and rapidly when present. Smears or aspirates from the lesions in sporotrichosis are usually negative on direct examination (not done in this case) and no useful serology is available. AFB, Giemsa, and PAS stains of the biopsy were negative and a smear for Leishmania was negative. The patient had been referred to us initially for treatment of presumed refractory leishmaniasis. This case reinforces the difficulty in making a clinical distinction between the two diseases and each must be definitively investigated in every nodular or ulcerative lesion seen in Perú.

Discussion: Sporothrix schenkii was cultured [Images C, D] from an aspirate from the border of an ulcer, the best place to sample for both sporotrichosis and leishmaniasis. In culture of scrapings, aspirates or biopsy material on Sabouraud’s agar, S. schenkii grows very easily and rapidly when present. Smears or aspirates from the lesions in sporotrichosis are usually negative on direct examination (not done in this case) and no useful serology is available. AFB, Giemsa, and PAS stains of the biopsy were negative and a smear for Leishmania was negative. The patient had been referred to us initially for treatment of presumed refractory leishmaniasis. This case reinforces the difficulty in making a clinical distinction between the two diseases and each must be definitively investigated in every nodular or ulcerative lesion seen in Perú.