|

Gorgas Case 2014-01 |

|

| Diagnosis: Neurocysticercosis due to Taenia solium. Subarachnoid form. |

| Acknowledgement: We thank Dr. Hector Hugo-Garcia of the Cysticercosis Unit of the Institute of Neurologic Sciences, Cayetano Heredia University in Lima for advice on this patient. |

|

Separate clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic considerations apply to patients with the three other forms of neurocysticercosis: intraparenchymal, ventricular, or intramedullary. See Gorgas Cases2011-06, 2007-02, and 2006-04 for discussion of these presentations. Cysticercosis is infection with the larval stages of the human pork tapeworm Taenia solium. Humans acquire cysticercosis after ingesting eggs of T. solium in material contaminated with feces originating in human tapeworm carriers. Humans that do not eat pork can get cysticercosis. Ingestion of contaminated pork results in humans getting an adult intestinal tapeworm – not cysticercosis. Cysticercosis is common in many developing countries and very common in rural agricultural areas of Perú. In developed countries, the long-lived cysticerci are increasingly seen as immigration from affected areas rises. Occasional transmission by tapeworm carriers to those who have never left non-endemic countries is reported. Ingested T. solium eggs hatch in the stomach and are then carried to the muscles and other tissues where the larvae encyst and reach their usual size of about 1 cm within a few months. The cysticerci seem able to evade the immune system and are thought to remain viable for several years without causing any inflammatory response, so that most infected patients are asymptomatic for years alter infection. Most clinical symptoms are the direct result of inflammatory responses that accompany the eventual cyst degeneration, but most patients likely remain asymptomatic even as cysts die. Epileptic seizures are the primary or sole clinical manifestation in up to 80% of symptomatic patients. In endemic regions new onset seizures in teenagers or young adults is most likely due to neurocysticercosis. Cysticerci can also cause symptoms because of mass effect, impingement on a vital structure or, especially if the cyst is intraventricular, blockage of CSF circulation. This patient is unfortunate to have a subarachnoid cyst, which represents the most problematic location, with the poorest prognosis, and which is the most difficult to treat. Intracranial hypertension is the main cause of symptoms of sub-arachnoid cysticercosis and the major cause of mortality among infected patients. Cases treated only with CSF diversion, are usually fatal over 5–10 years from clinical presentation. However, prolonged inflammation and leptomeningeal irritation after albendazole therapy may result in a prolonged need for steroid therapy with significant clinical exacerbations during weaning attempts. In general, prolonged courses of albendazole starting with a minimum of 2 months should be used in patients with sub-arachnoid cysts, but more careful follow-up, in-patient admission, and a willingness to place an intraventricular drain if necessary is involved in the care of such patients. In all cysticercosis patients, seizures need to be managed with anti-convulsants as per any other form of epilepsy. For our patient we began a planned 2 months of albendazole combined with a higher than usual dose of dexamethasone (4 mg po qid) because of the sensitive location of the cyst. She was also begun on phenytoin and carbamazepine. The patient responded well with a dramatic improvement of her headaches and well being, with no further acute episodes. After 3 weeks of therapy, steroids were tapered to 50 mg/day of prednisone. Five days subsequently the patient began to have acute episodic confusion, blurred vision, and tonic-clonic movements of her left upper and lower extremities. This required re-institution of dexamethasone 8 mg/day with subsequent stabilization. The patient will also have a spinal MRI to rule out any intra-medullary disease, which occurs at an increased frequency in individuals with sub-arachnoid disease. In general, patients should receive albendazole until subarachnoid cysts resolve radiologically; our patient will be assessed after the initial 2-month course. It is generally difficult to stop steroids while patients are still receiving albendazole, although very, very slow attempts at tapering – perhaps slower than in this patient – should be started after 2-3 weeks on albendazole. When extremely prolonged courses of albendazole are needed, some clinicians have begun to use methotrexate up to 20 mg/week as a steroid-sparing agent but there are only small cases series to support this. |

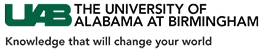

Discussion: This case illustrates the limitations of CT scan alone in fully assessing patients with possible neurocysticercosis. Two CT scans in this case – Image A as well as one done on admission to our hospital (not shown) – were reviewed and were normal. The MRI shown in Image B demonstrates a single fluid-filled cystic lesion in the sub-arachnoid space in the temporo-parietal fissure on both coronal and transverse cuts. The lesion is adjacent to the left side of the optic chiasm. On the periphery of the cyst, a single punctiform structure compatible with the scolex is seen [see

Discussion: This case illustrates the limitations of CT scan alone in fully assessing patients with possible neurocysticercosis. Two CT scans in this case – Image A as well as one done on admission to our hospital (not shown) – were reviewed and were normal. The MRI shown in Image B demonstrates a single fluid-filled cystic lesion in the sub-arachnoid space in the temporo-parietal fissure on both coronal and transverse cuts. The lesion is adjacent to the left side of the optic chiasm. On the periphery of the cyst, a single punctiform structure compatible with the scolex is seen [see