|

Gorgas Case 2023-10 |

|

|

The following patient was seen as an inpatient in the Internal Medicine ward of Cayetano Heredia Hospital in Lima by the 2023 Gorgas Advanced Course participants.

History: A 54-year-old patient presented with a one-week history of intermittent dizziness and holocranial headaches. On the day of admission, he presented sudden-onset weakness and numbness in the upper right extremity and decided to go to the emergency room. On the way there, his family describes an episode of transient loss of consciousness with sphincter relaxation and a post-ictal period. Epidemiology: Born in Cajamarca, in the northern highlands of Peru, where he lived until 8 years of age in a farm in a rural community and cared for animals including cows, pigs, sheep and dogs. Lived in Trujillo until 18 years of age, working in animal husbandry. Currently lives in the city of Lima, where he has no pets. Traveled back to Cajamarca one year before presentation. Past medical history: Episode of Bell’s palsy in 2019, which resolved after treatment with steroids. No known tuberculosis contacts. Laboratory: Hb 15, Plt 290 000, WBC 17 960 (0% bands, 0.11% eosinophils, 16.6% neutrophils, 0.5% lymphocytes). Glucose 120, Na 146, K 4.08, Cl 108.

|

|

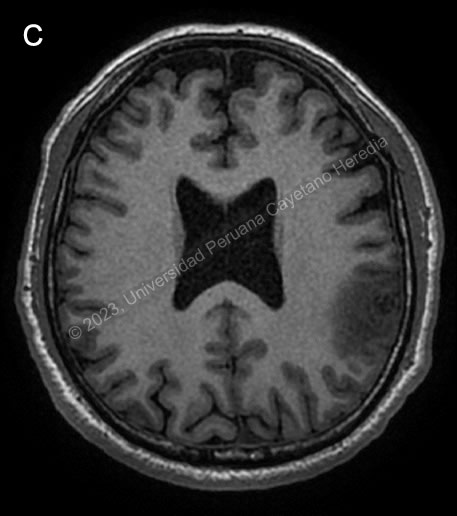

Diagnosis: Parenchymal neurocysticercosis

Discussion: Brain CT showed a calcified lesion with surrounding edema in the left parietal lobe and additional calcified nodular lesions with no edema in the left occipital lobe. The lower limb x-ray showed a cigar-shaped calcification compatible with a calcified cysticercus. Brain MRI (Image C) confirmed these findings, showing an irregular nodular cortico-subcortical lesion of heterogenous aspect with peripheral vasogenic edema in the left parietal lobe, and the previously described left occipital lesions. A diagnosis of neurocysticercosis was made with these images. |