|

Diagnosis: Disseminated juvenile Paracoccidioidomycosis and tuberculous lymphadenitis

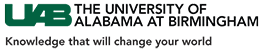

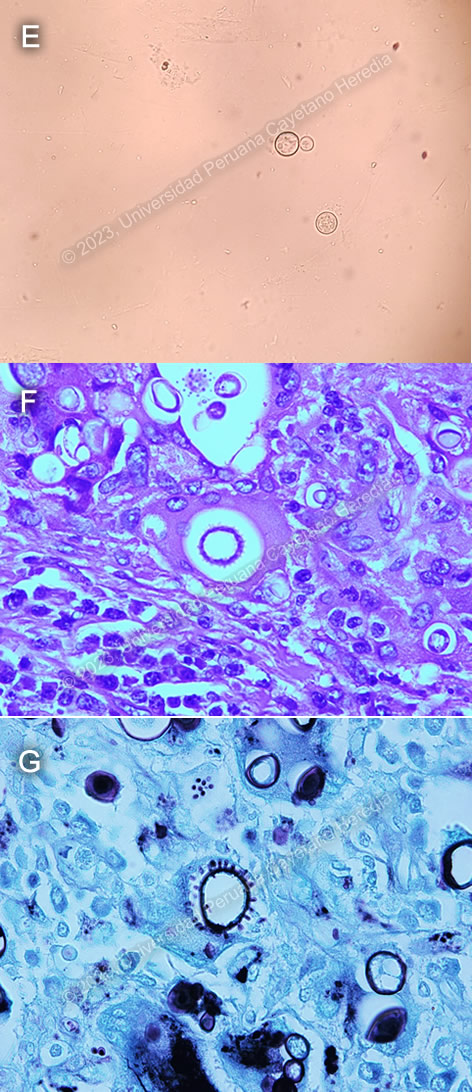

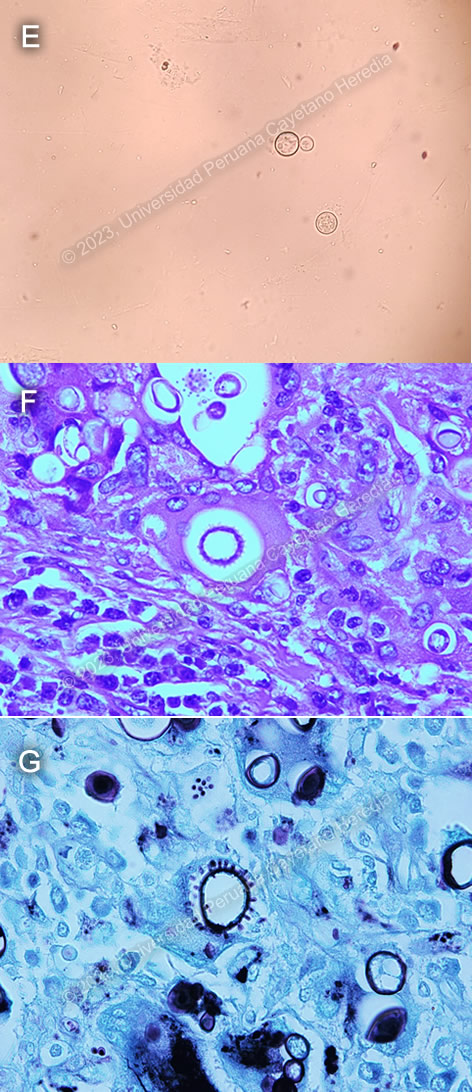

Discussion: A KOH of a sputum sample (Image E) showed large, oval, double walled cell with budding daughter cells, characteristic for Paracoccidioides spp. Histopathology of lymph node biopsy showed chronic granulomatous formations with yeast forms of varying sizes (5-30μm) in H&E staining (Image F), and a Grocott stain showing some of them with multiple peripheral budding in a “pilot wheel” pattern, suggestive of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (Image G). Ziehl-Neelsen stains were negative for acid-fast bacilli.

This case highlights a classical presentation of the juvenile form of paracoccidioidomycosis, with prominent reticuloendothelial system involvement. A cohort study conducted among pediatric patients in Brazil found that lymphadenopathy, fever, weight loss, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly were among the most frequent clinical findings in juvenile paracoccidioidomycosis1. Liver and spleen enlargement are frequently described, and the most commonly involved lymph nodes include those of the head, and the supraclavicular and axillary chains. Skin lesions, which are usually papular, are most frequently seen on the face2. Reticuloendothelial system involvement can also lead to bone marrow dysfunction, which may explain our patient’s anemia.

Diagnosis usually relies on identification of Paracoccidioides spp in clinical or histopathological specimens. Typical forms include a mother yeast cell surrounded by budding daughter yeast cells in a “pilot wheel” pattern or surrounded by only two daughter buds in a “Mickey mouse head” pattern.

Paracoccidioidomycosis is geographically restricted to central and South America, with the highest prevalence in Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela and Argentina.3 Some imported cases have also been reported in Europe, North America, Asia and Africa4.

Paracoccidioidomycosis was thought to be caused solely by P. brasiliensis, but the use of molecular tools has shown that there are at least four different lineages with pathogenic potential for humans. P. americana has been isolated in Brazil, Venezuela, Uruguay and Argentina; P. restrepiensis in Colombia; P. lutzii predominantly in western and central Brazil. Only P. brasiliensis has been isolated in Peru, though there have been few molecular studies conducted. There seems to be no difference in clinical manifestations or therapeutic response between patients infected with P. brasiliensis and P. lutzii, though cases with P. lutzii may have negative serological test that detect antibodies against gp435.

Treatment should be started with itraconazole in mild to moderate cases, or with amphotericin B for severe and disseminated forms. Duration of treatment with amphotericin depends on the clinical response and should be kept as short as possible. Clinical response is measured using reduction of symptoms or signs, stabilization of body weight, clearing of chest X-rays, and appropriate serum antibody titers. Treatment with itraconazole for 9-18 months should follow.

A GeneXpert performed on our patient’s cervical lymph node biopsy was positive for rifampicin-sensible Mycobacterium tuberculosis. WHO recommends only using Xpert in sputum, CSF or lymph node tissue; testing stool, urine or blood is not recommended as there is scanty data on utility of Xpert for these specimens. Xpert MTB/RIF has a good diagnostic efficiency for lymph note tuberculosis, with reported sensitivities for fine needle aspiration and tissue biopsies as high as 80% and 76%, respectively6.

An association between paracoccidioidomycosis and tuberculosis has been described in Brazil, with rates of coinfection as high as 15.8%7, though overlap between the clinical presentation of both diseases may lead to misdiagnosis in some cases. Our patient was started on treatment with amphotericin B for paracoccidioidomycosis. First-line antituberculous treatment was withheld because of liver involvement as evidenced by hepatic enzymes elevated above 5 times the upper limit of normal; instead, he was started on a non-hepatotoxic treatment regimen with meropenem, amoxicillin-clavulanate, amikacin and ciprofloxacin on the advice of the tuberculosis consultant.

Treatment of paracoccidioidomycosis-tuberculosis coinfection can be challenging because of significant interactions between two cornerstones of treatment – itraconazole and rifampicin. In these cases, itraconazole can be substituted for cotrimoxazole, which is a good fungistatic but requires a longer treatment duration than itraconazole. Our patient continues to be monitored in-hospital. Primary immunodeficiency workup is pending.

References:

1. Romaneli MT das N, Tardelli NR, Tresoldi AT, Morcillo AM, Pereira RM. Acute-subacute paracoccidioidomycosis: A paediatric cohort of 141 patients, exploring clinical characteristics, laboratorial analysis and developing a non-survival predictor. Mycoses. 2019;62(11):999-1005. doi:10.1111/myc.12984

2. Marques SA. Paracoccidioidomycosis. Clinics in Dermatology. 2012;30(6):610-615. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2012.01.006

3. Bocca AL, Amaral AC, Teixeira MM, Sato PK, Shikanai-Yasuda MA, Soares Felipe MS. Paracoccidioidomycosis: eco-epidemiology, taxonomy and clinical and therapeutic issues. Future Microbiology. 2013;8(9):1177-1191. doi:10.2217/fmb.13.68

4. Martinez R. New Trends in Paracoccidioidomycosis Epidemiology. Journal of Fungi. 2017;3(1):1. doi:10.3390/jof3010001

5. Marques-da-Silva SH, Messias Rodrigues A, de Hoog GS, Silveira-Gomes F, Pires de Camargo Z. Occurrence of Paracoccidioides lutzii in the Amazon Region: Description of Two Cases. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87(4):710-714. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0340

6. Yu G, Zhong F, Ye B, Xu X, Chen D, Shen Y. Diagnostic Accuracy of the Xpert MTB/RIF Assay for Lymph Node Tuberculosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:4878240. doi:10.1155/2019/4878240

7. Quagliato Júnior R, Grangeia T de AG, Massucio RA de C, De Capitani EM, Rezende S de M, Balthazar AB. Association between paracoccidioidomycosis and tuberculosis: reality and misdiagnosis. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33(3):295-300. doi:10.1590/s1806-37132007000300011

|