|

Gorgas Case 2023-04 |

|

|

The following patient was seen on the inpatient ward of Cayetano Heredia Hospital in Lima by the 2023 Gorgas Course participants.

History: A 20-year-old previously healthy male patient presented with a 7-day history starting with high fevers (quantified at 39.5°C), headache, myalgias, arthralgias and retroocular pain. Three days before admission, he started to have nausea, one episode of vomiting and diarrhea (watery, no mucus or blood), and noticed a rash which started on his back and then generalized; the rest of the symptoms persisted. Two days before admission, the diarrhea and vomiting ceased but all other symptoms persisted. On the day before admission, he sought medical care and had blood tests drawn. He was referred to our institution with the results of these tests. He denied any bleeding. Epidemiology: Born in Jaen, Cajamarca, in the northern high jungle of Peru, where he lived until he was 13 years. Currently lives in Lima, where he is a 2nd year medical student. He travels back to Jaen during school holidays to help with the family business, a fish import company. He was last in Jaen two months before admission, and he remained there until the day before admission when he traveled to Lima. He swam in rivers but not stagnant waters, did not go into caves, used insect repellent intermittently, and was bitten by mosquitoes multiple times. No animal exposures. No known tuberculosis exposures. Past medical history: Had dengue at 8 years of age, while living in Jaen. Has received all childhood immunizations, including yellow fever vaccine. Drinks alcohol socially, no smoking or other recreational drug use. No sexual contacts in the last four months. Laboratory: Hemoglobin 15.5, hematocrit 47. WBC 5.27 (54.1% lymphocytes, 0% bands, 9.5% monocytes, 34.4% neutrophils, 1.8% eosinophils, 0.1% basophils). Platelets 46 000. PT 12.8, aPTT 44.4, INR 0.93. Glucose 83, Urea 30, Creatinine 0.53. AST 292, ALT 195, Alkaline phosphatase 103, GGT 224. HIV-1/2 negative.

|

|

Diagnosis: Presumptive dengue without alarm signs.

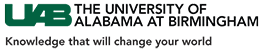

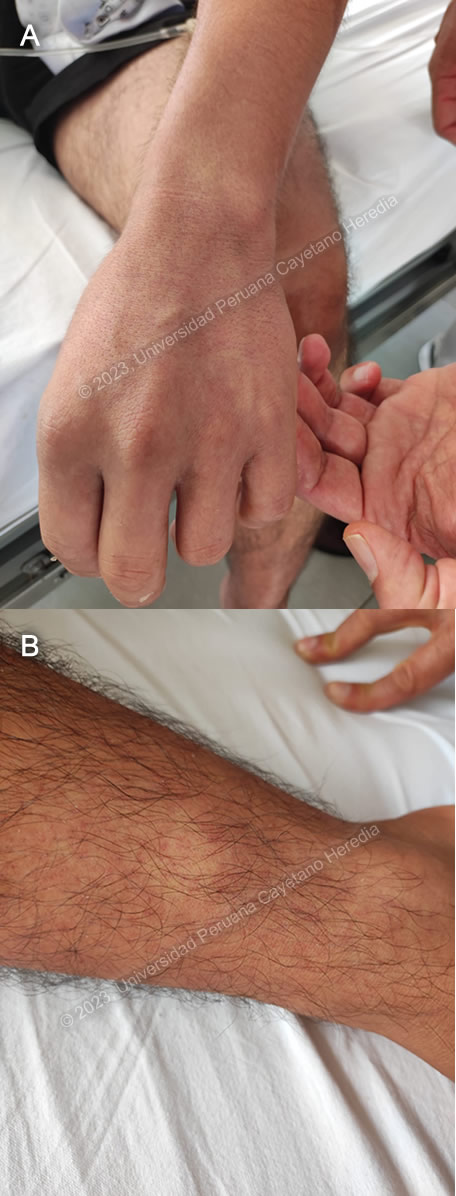

Discussion: A Thick and thin smears were negative for malaria, and a COVID-19 antigen test was negative. Though no confirmatory tests for dengue were performed, a presumptive diagnosis was made on the basis of the patient’s symptoms, exposure, and exclusion of other possible etiologies. During the first week of illness, a diagnosis of dengue can be established with NS1 (viral antigen nonstructural protein 1) detection or PCR, though sensitivity of NS1 diminishes in secondary infections1. ELISA for IgM can be positive from four days after symptom onset, thus this is the more appropriate test for this patient. Results are pending. A tourniquet test was performed by inflating a sphygmomanometer to the patient’s mean arterial blood pressure and keeping it inflated for 5 minutes. Afterwards, the number of petechiae in an area measuring one square inch in the antecubital fossa was counted (Image C). If there are more than 10 petechiae, as was the case with this patient, the tourniquet test is considered to be positive. |