|

Diagnosis: Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis

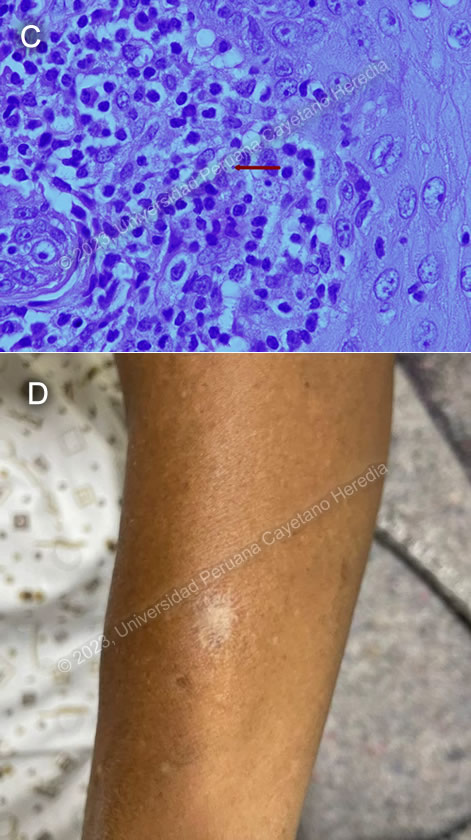

Discussion: SBiopsy of the laryngeal lesion seen on fibro bronchoscopy showed scanty ovoid structures about 3 μm in diameter with a large nucleus and kinetoplast, compatible with Leishmania sp. amastigotes (Image C). When deciding the best location for a biopsy, there is good evidence to support taking a sample from the edges of the lesion in cutaneous leishmaniasis, as this is where there is more likelihood of finding a parasite. However, in mucosal leishmaniasis, parasites are often hard to find and biopsies can be taken from any of the granulomatous lesions.

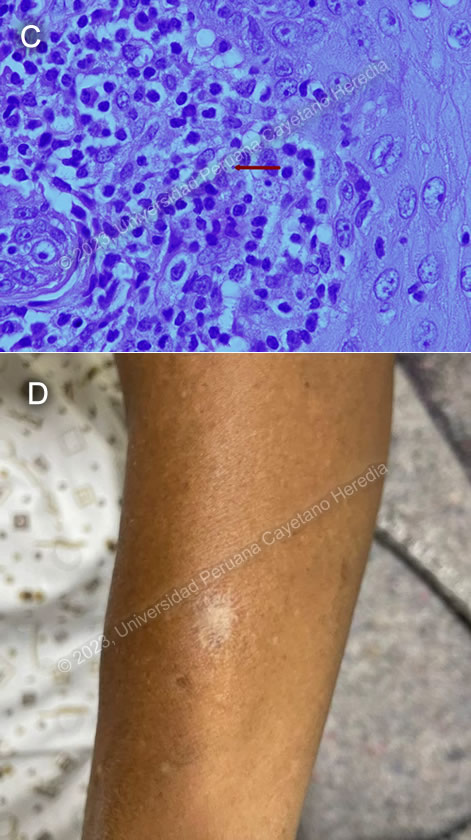

Upon further questioning, the patient recalled that at 19 years of age, while living in Tingo Maria, he had had a painless, pruritic ulcer with elevated borders in the left forearm, which he treated topically with alcohol and iodine until it scarred (Image D). It is crucial to specifically look for evidence of past cutaneous leishmaniasis during the physical exam as scars can be easily missed. He also revealed that several of his family members had had “uta”, the local name for cutaneous leishmaniasis, in the past. In a study conducted among patients with mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in Brazil, 79% has a concomitant cutaneous lesion or scar suggestive of past leishmaniasis1.

Our patient had had a previous diagnosis of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis with full treatment with amphotericin B deoxycholate twice. When a patient presents with recurrent lesions in the context of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, it is important to distinguish between reactivation and reinfection. Though our patient had continued exposure throughout the time of illness, the literature shows that at least 50% of cases of recurrent disease are due to reactivation, particularly when the disease-free interval is shorter and recurrent lesions are closer to the initial lesion2. Immunological factors that have been associated with relapse include higher CD8+ T and IFN-γ producing cell levels and a poor regulatory response3. When patients receive multiple courses of treatment such as in this case, it may be difficult to find amastigotes in scrapings or biopsies, as it was in this case.

L. braziliensis is the most likely Leishmania species present in the area where he lived at the time of his initial infection. However, in South America, it is important to definitively distinguish Leishmania species that cause only cutaneous disease (e.g., L. peruviana in Perú) from the mucocutaneous species, which include L. guyanensis and L. panamensis in addition to L. braziliensis. Patients infected with cutaneous or mucocutaneous leishmaniasis typically present initially with one or a few initial skin lesions that are ulcerative but painless in nature and that usually spontaneously heal over time. However, with mucocutaneous species, severe destructive recurrence may occur in the mucosal surfaces of the naso- and oropharynx from months to years after treatment or healing of the skin ulcers; this period has been reported to be as long as 50 years in some cases4. In this part of the world, the vector is the Lutzomyia sandfly.

Mucosal leishmaniasis can present in varying degrees of severity, ranging from mild disease involving only the oral or nasal cavity to very severe forms involving vocal cords, and even the trachea or bronchi5. IDSA guidelines recommend that patients with laryngeal or pharyngeal disease at increased risk for respiratory obstruction should receive prophylactic corticosteroid treatment due to potential inflammatory reactions after initiating antileishmanial treatment6. PAHO has recently released guidelines for the treatment of leishmaniasis in the Americas, which recommends using pentavalent antimonials with or without oral pentoxifylline for mucosal and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis7. However, the choice of antileishmanial agent should be individualized; other options include liposomal or deoxycholate amphotericin B, or miltefosine. Relapses do not necessarily indicate drug failure, thus reinduction therapy with the initial agent may be justified, but monotherapy or combination therapy with different agents can also be considered. There is no recommendation to extend treatment or change to a specific antileishmanial agent.

Our patient is receiving a course of steroids to reduce swelling of the laryngeal lesions, which will be tapered off prior to starting treatment with amphotericin B deoxycholate once again. The choice of medication is due to unavailability of other drugs in our setting. He will be closely monitored during the first days of antiparasitic treatment and will receive a tracheostomy if necessary.

References:

1. Cincurá C, de Lima CMF, Machado PRL, et al. Mucosal leishmaniasis: A Retrospective Study of 327 Cases from an Endemic Area of Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97(3):761-766. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0349

2. Saravia NG, Segura I, Labrada LA, et al. Recurrent lesions in human Leishmania braziliensis infection—reactivation or reinfection? The Lancet. 1990;336(8712):398-402. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(90)91945-7

3. Tuon FF, Gomes-Silva A, Da-Cruz AM, Duarte MIS, Neto VA, Amato VS. Local immunological factors associated with recurrence of mucosal leishmaniasis. Clinical Immunology. 2008;128(3):442-446. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2008.05.007

4. Schleucher RD, Zanger P, Gaessler M, Knobloch J. Successful diagnosis and treatment 50 years after exposure: is mucocutaneous leishmaniasis still a neglected differential diagnosis? J Travel Med. 2008;15(6):466-467. doi:10.1111/j.1708-8305.2008.00261.x

5. Carvalho EM, Llanos-Cuentas A, Romero GAS. Mucosal leishmaniasis: urgent need for more research. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2018;51:120-121. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0463-2017

6. Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Leishmaniasis: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(12):e202-e264. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw670

7. Pan American Health Organization. Guideline for the treatment of leishmaniasis in the Americas. Second edition. Published online 2022. https://doi.org/10.37774/9789275125038.

|