- Details

- Written by: Addie Knight

In many of our previous blog posts we have written about the main subjects of our experiment, three wonderful amphipod species Prostebbingia gracilis, Gondogeneia antarctica, and Djerboa furcipes. For simplicity we call them P. gracilis, Gondo and Djerboa, resp. As Hannah mentioned in her blog post Getting Experimental, in one of our last season’s experiment, Djerboa were found to respond better to lower pHs than P. gracilis and Gondo. Our current experiment will hopefully help us better understand the reasons for those differences. Below is a group of Gondo sorted from the other amphipods. Hannah’s post also has a nice close-up of Gondo.

- Details

- Written by: Chuck Amsler

In my last post, I talked about how unusually bad weather for January had been limiting our diving activities. I also mentioned being able to dive right off the station dock sometimes when the winds are too strong to go out in boats but from a direction where the dock area is protected from the waves. The weather has gotten better, but we have been diving at the dock a lot anyway. Why you might ask??

- Details

- Written by: Hannah Oswalt

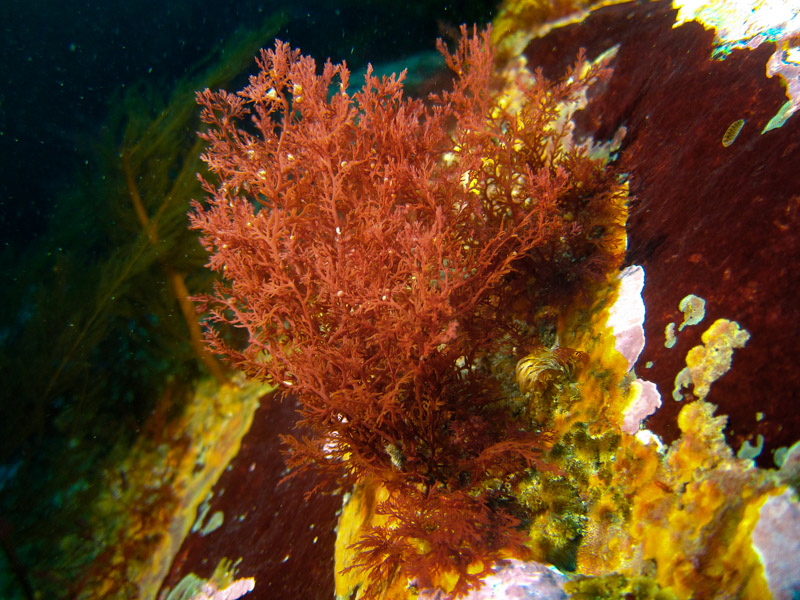

How do you get to Crustaceanland? That is the question our group is trying to answer this week as we gather amphipods for our experiment. Here on the Western Antarctic Peninsula, our study organisms can usually be found hiding amongst the large seaweeds that dominate the benthos of shallow water communities. When we want to collect amphipods, our divers will cut the base of the seaweed and gently float it into a fine mesh bag. The amphipods we want will stay on the seaweed as long as we don’t jostle the alga too much. Voilà, we have just caught some amphipods. Easy-peasy. Mission accomplished… or is it? We may have amphipods in a bag but there are still several more steps that need to be completed before we have amphipods that are usable.

How do you get to Crustaceanland? That is the question our group is trying to answer this week as we gather amphipods for our experiment. Here on the Western Antarctic Peninsula, our study organisms can usually be found hiding amongst the large seaweeds that dominate the benthos of shallow water communities. When we want to collect amphipods, our divers will cut the base of the seaweed and gently float it into a fine mesh bag. The amphipods we want will stay on the seaweed as long as we don’t jostle the alga too much. Voilà, we have just caught some amphipods. Easy-peasy. Mission accomplished… or is it? We may have amphipods in a bag but there are still several more steps that need to be completed before we have amphipods that are usable.

- Details

- Written by: Maggie Amsler

Team UAB in Antarctica has been diving far and wide in the Palmer Station vicinity searching for algae laden with amphipods for our ocean acidification experiment. The hunt always yields algae but not always amphipods, much less the particular species and numbers desired for the ocean acidification experiment. The divers are sort of like Goldilocks looking for an alga that is not too big (to handle), not too small (yielding low amphipod abundances), but just right size (to fit in our special collecting bags and have good numbers of the amphipods of interest). As we swim about looking for that perfect alga, we often get distracted by other types of critters living on the seafloor. I’d like to introduce you to some of those cool creatures we have encountered – in particular those with many arms and many legs.

Team UAB in Antarctica has been diving far and wide in the Palmer Station vicinity searching for algae laden with amphipods for our ocean acidification experiment. The hunt always yields algae but not always amphipods, much less the particular species and numbers desired for the ocean acidification experiment. The divers are sort of like Goldilocks looking for an alga that is not too big (to handle), not too small (yielding low amphipod abundances), but just right size (to fit in our special collecting bags and have good numbers of the amphipods of interest). As we swim about looking for that perfect alga, we often get distracted by other types of critters living on the seafloor. I’d like to introduce you to some of those cool creatures we have encountered – in particular those with many arms and many legs.

- Details

- Written by: By Addie Knight

Palmer station has a maximum capacity of only 45, so everyone living here gets to know each other really well and really fast. Most evenings there’s some fun activity going on, which varies depending on who’s on station and what they’re interested in, but this season so far we have been having a scary movie series, video game competitions, card games, yoga, hiking outings and lots more. One afternoon Hannah and I plus other station folks walked up the glacier to take in the sites (see photo of us below).

- Details

- Written by: By Hannah Oswalt

The last time we talked, I briefly mentioned the objective of our experiment for this field season. If you don’t remember, let me refresh your memory.

- Details

- Written by: Charles Amsler

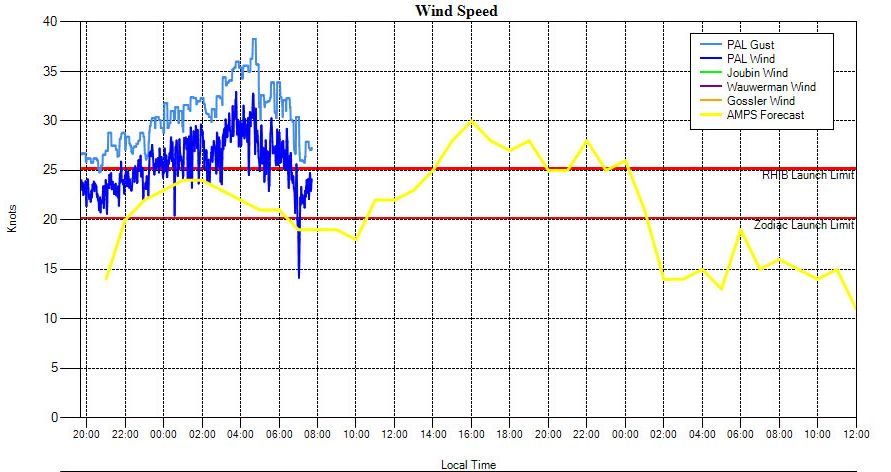

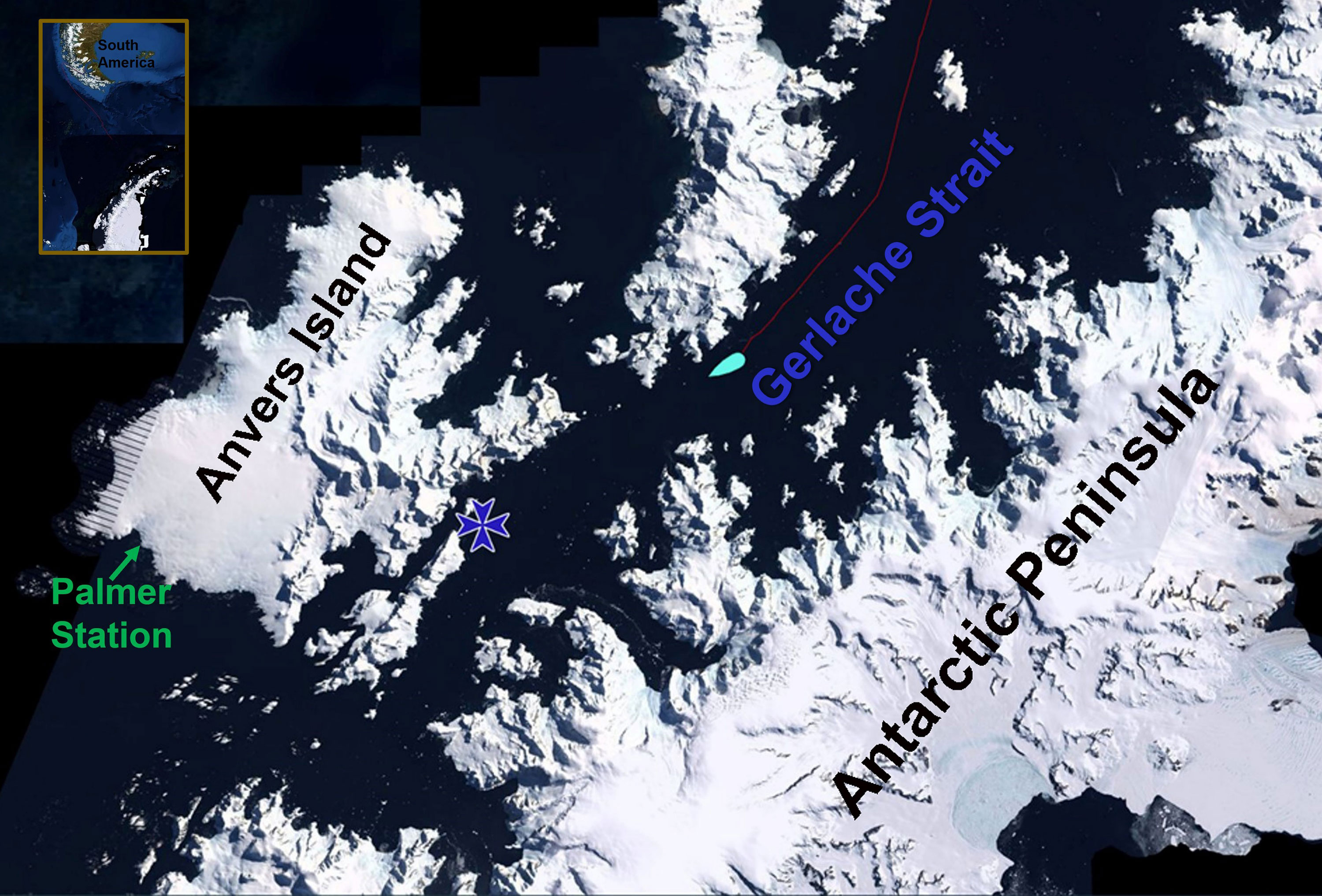

I had planned for this post to be about diving, but we’ve done much less of it so far than expected. Why you might ask? Because of the weather.

I had planned for this post to be about diving, but we’ve done much less of it so far than expected. Why you might ask? Because of the weather.

- Details

- Written by: Jim McClintock

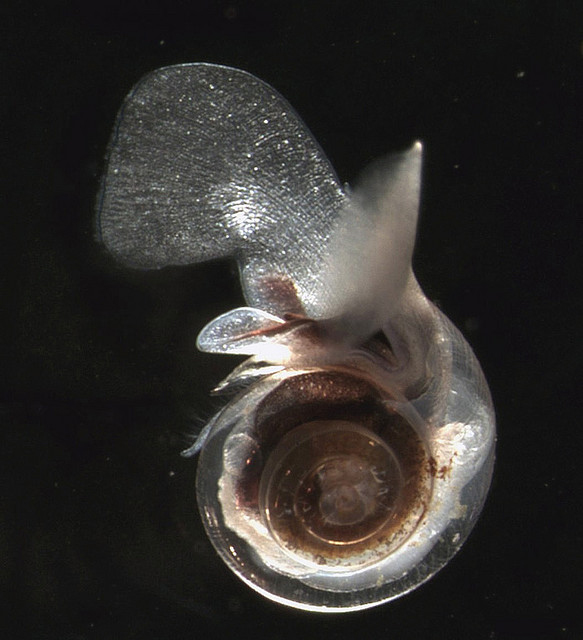

I am going to expand on the excellent introduction Hannah gave you to the science of ocean acidification (OA) in an earlier blog. In doing so, I will highlight some of the bigger picture implications of ocean acidification globally. I will focus on two different cold-water geographic regions of the world and for each briefly highlight the impacts of ocean acidification on key, ecologically or economically (or both) important marine organisms. Both regions are ‘hot spots’ for ocean acidification.

I am going to expand on the excellent introduction Hannah gave you to the science of ocean acidification (OA) in an earlier blog. In doing so, I will highlight some of the bigger picture implications of ocean acidification globally. I will focus on two different cold-water geographic regions of the world and for each briefly highlight the impacts of ocean acidification on key, ecologically or economically (or both) important marine organisms. Both regions are ‘hot spots’ for ocean acidification.

- Details

- Written by: Addie Knight

After settling in, the team began preparing for our first dives, and there was a lot for me to learn. We practiced setting up a tent and starting a camp stove in case we could not get back to station due to weather and had to seek refuge on an island. We also learned how to tie various hitches and knots for use on the zodiac boats.

After settling in, the team began preparing for our first dives, and there was a lot for me to learn. We practiced setting up a tent and starting a camp stove in case we could not get back to station due to weather and had to seek refuge on an island. We also learned how to tie various hitches and knots for use on the zodiac boats.

- Details

- Written by: Hannah Oswalt

It’s a cold winter’s morning. You sit in the driver’s seat of a car and turn on the engine, giving it a few minutes to warm up before making your morning commute. Perhaps, instead of a car, you are on a bus, train, or plane. In all of these scenarios, you are producing a common thing. Carbon dioxide (CO2).

It’s a cold winter’s morning. You sit in the driver’s seat of a car and turn on the engine, giving it a few minutes to warm up before making your morning commute. Perhaps, instead of a car, you are on a bus, train, or plane. In all of these scenarios, you are producing a common thing. Carbon dioxide (CO2).

- Details

- Written by: Maggie Amsler

I felt like a cuckoo clock the night before we reached Palmer Station. As I slept in the top bunk of my cabin, seemingly on the hour I woke and sat up wondering if we were there yet. Peering out the porthole conveniently located at mattress level by my knees I could see our ship, the Laurence M. Gould (LMG) was still a ways offshore to go yet. Back to sleep.

- Details

- Written by: Addie Knight

When our group (Chuck, Maggie, Hannah, and I) boarded the LMG, more formally known as Laurence M. Gould, the ship which would take us from Punta Arenas to Palmer Station, I thought that it felt much more like a boat than any other boat I’ve been on.

When our group (Chuck, Maggie, Hannah, and I) boarded the LMG, more formally known as Laurence M. Gould, the ship which would take us from Punta Arenas to Palmer Station, I thought that it felt much more like a boat than any other boat I’ve been on.

- Details

- Written by: Hannah Oswalt

My parents and brother hugged me one last time before I left my family to join the line for TSA at the Huntsville Airport. We would see each other again, but that wouldn’t be until May, nearly five months from now.

My parents and brother hugged me one last time before I left my family to join the line for TSA at the Huntsville Airport. We would see each other again, but that wouldn’t be until May, nearly five months from now.

- Details

- Written by: Charles Amsler

It was the evening of March 18th, 2020 at Palmer Station, Antarctica. As Station Science Leader (SSL), I had the luxury of my own office, and was there having a sobering conversation with Bob Farrell, the Station Manager and a long-time friend.

It was the evening of March 18th, 2020 at Palmer Station, Antarctica. As Station Science Leader (SSL), I had the luxury of my own office, and was there having a sobering conversation with Bob Farrell, the Station Manager and a long-time friend.

- Details

- Written by: Maggie Amsler

UAB Antarctica field team members meet on campus before heading south. Keep an eye on this page for the initial entry of the expedition. In the meantime, get to know the group by reading their bios in Meet the Team.

UAB Antarctica field team members meet on campus before heading south. Keep an eye on this page for the initial entry of the expedition. In the meantime, get to know the group by reading their bios in Meet the Team.- Details

- Written by: Maggie Amsler

A mesmerizing symphony of pastel reds and blues entranced Palmer Station and many a camera the other morning. The shifting color palette not only soothed and appeased our gray-weary community; the lively color medley energized us as well. This was the undeniable dawn of a new day and in retrospect for me a harbinger of the coda – shifting, waiting in the wings….

- Details

- Written by: Sabrina Heiser

If you consult Wikipedia (I would not recommend it as a scientific source though) you will read that “a transect is a path along which one counts and records occurrences of the species of study (e.g. plants)”.

- Details

- Written by: Michelle Curtis

Naturalist = Student of natural history (the scientific study of observations of plants and animals).

Antarctica = The earth’s southernmost continent. Also, one of the most remote and pristine habitats dominated by natural flora and fauna and virtually untouched by humans.

- Details

- Written by: Jim McClintock

The UAB Antarctica team members, faculty, research associate, and graduate students, are all on the lookout to amplify the impact of our educational outreach program, or in the parlance of the National Science Foundation, ‘broaden our impacts.’ This may be accomplished in myriad ways.

- Details

- Written by: CJ Brothers

Sea stars are probably not the first animal you think of when you think about Antarctica. But, they are some of the most abundant animals in the shallow waters surrounding Palmer Station.