|

Gorgas Case 2022-08 |

|

|

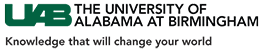

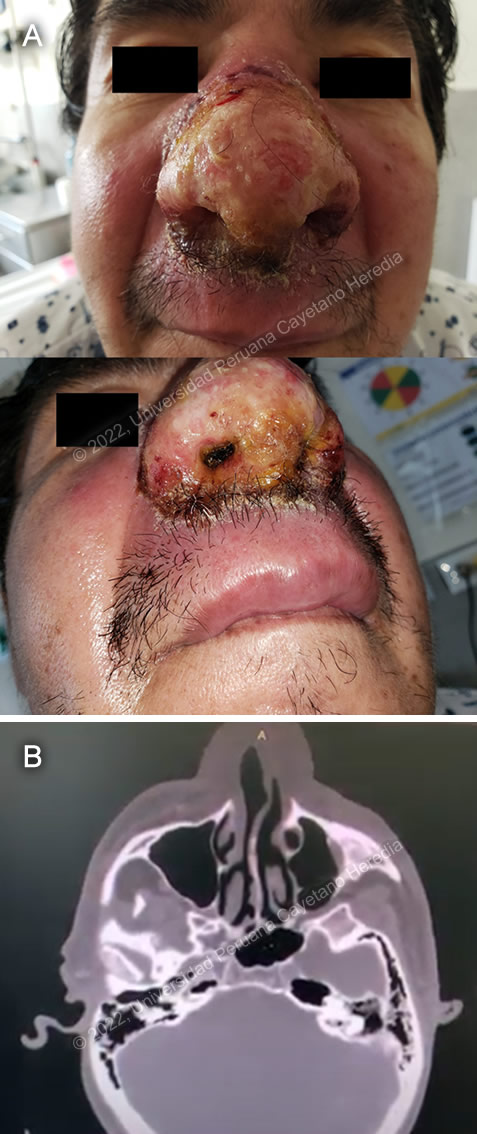

The following patient was seen on the inpatient ward of Cayetano Heredia Hospital in Lima by the 2022 Gorgas Course participants.  History: A 57-year-old man presented with a 1-month history of redness and pruritus around the septum of the nose, which became indurated and painful after three days. On day 7, he noticed swelling of the nose, and painful round masses in his submandibular area. On day 13, the nasal lesion ulcerated, and painful scabs appeared. He applied alcohol to the area. On day 15, he went to a private clinic where a biopsy was taken. On day 21, he applied chamomile tea to his nose and removed the scabs, causing pulsating pain. On day 30, the day of admission, he went to get the results of his biopsy, but they were unavailable, and he decided to come to the emergency department at our institution. Epidemiology: He was born in Chiclayo, in the northern coast of Peru, and has lived in Lima since he was 19 years old. He works as a carpenter. He traveled to Yurimaguas, Loreto (in the Amazon basin) 40 days before admission, where he swam in lakes and rivers. He has no known TB contacts or ill family members. Past Medical History: No history of other illnesses. Had surgery for an inguinal hernia as a child, and for traumatic brain injury 20 years ago. Physical Examination (on admission): T: 36.8°C, BP 170/100 mmHg, HR 72 bpm, RR 18 rpm, SatO2 97% on room air. Skin: Skin warm, dry, with good turgor. Centrofacial ulcer with fibrinous base over nose and upper lip, with myeliseric scabs around the edges and surrounding erythema (Image A). Oropharynx: No lesions in oral mucosa or tongue. Laboratory Results: Hb 14, Hct 42, Leu 5 650 (bands 0%, seg 71.5%, eos 0.5%, baso 0.4%, mono 9%, lymph 18.2%), Plt 341 000; PT 17.3, PTT 31.9, INR 0.9; BUN 26, Cr 0.8, Na 143, K 4.7, Cl 102; ALT 28, AST 26, LDH 177, GGT 67. Imaging: Head CT showed thinning of the nasal cartilage without perforation (Image B), other structures were without alteration. Chest Xray was normal.

|

|

Diagnosis: Cutaneous leishmaniasis

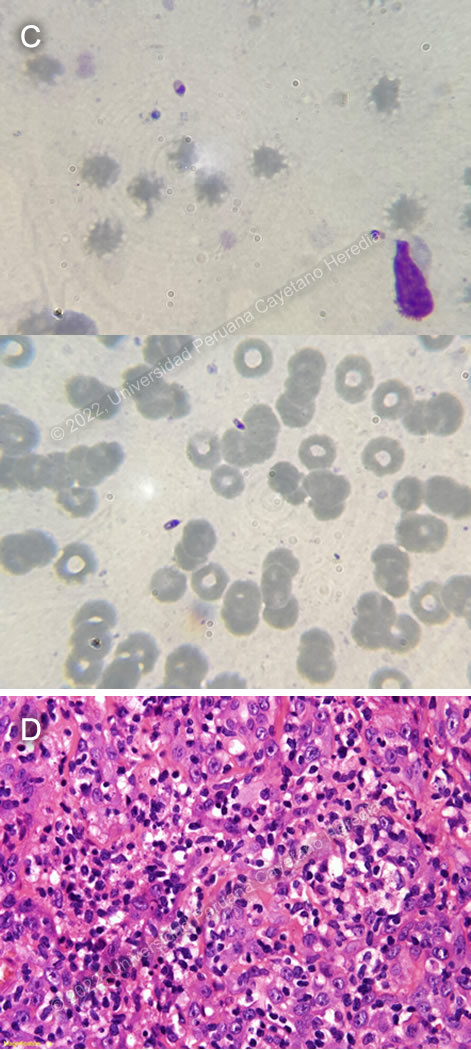

Discussion: A direct exam of a skin scraping (Image C) and skin biopsy (Image D) revealed Leishmania sp. amastigotes. PPD was negative. Direct smears and cultures for fungi and mycobacteria were negative. L. braziliensis is the only Leishmania species present in the area of the jungle where our patient traveled. However, in South America it is important to definitively distinguish Leishmania species that cause only cutaneous disease (e.g., L. peruviana in Peru) from the mucocutaneous species (L. braziliensis in Peru). Both typically cause one or a few initial skin lesions that are ulcerative but painless in nature and that usually spontaneously heal over time. However, with L. braziliensis, severe destructive recurrence may occur in the mucosal surfaces of the naso- and oropharynx from months to years after treatment or healing of the skin ulcers. L. braziliensis only occurs in the Americas and as part of the Viannia subgenus, can cause mucocutaneous disease. Other species in this subgenus include L. (V) amazonensis, L. (V) panamensis, and L. (V) guyanensis. In this part of the world the vector is the Lutzomyia sandfly. The literature describes an incubation time for cutaneous leishmaniasis ulcers of as little as 20 days after inoculation of the parasite (Arch Derm Syphilol. 1944;49(6):433-435); however, the presumed incubation period in this case does not seem to correlate with the size of the observed lesion. The major differential diagnoses of these lesions would be paracoccidioidomycosis, tuberculosis, lupus pernio sarcoidosis, or nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma. A centrofacial plaque in a case of infection by Balamuthia mandrillaris would present with a different clinical picture, and plaques are usually infiltrated instead of ulcerated. In Peru, leishmaniasis would be by far the most common. Lesions are usually painless despite widespread destruction of tissue, involvement of the mucosa, unless there is superinfection as was the case with our patient. Early superinfection may have been aided by his constant manipulation of the lesion. The nasal lesions could also be consistent with rhinoscleroma, a granulomatous bacterial infection caused by Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis. A search for the scar of the original cutaneous lesion, often subtle, usually on a limb, is a key part of the physical examination. Its absence may lend doubt to the impression of leishmaniasis, making this case atypical. In general, oral lesions of paracoccidioidomycosis are painful, are frequently friable and bleed on contact, and gingival and buccal mucosa are frequently involved. Gingiva and buccal mucosa are less often involved in leishmaniasis. The lungs are the primary site of infection in paracoccidioidomycosis and the x-ray is generally abnormal. KOH preps of direct scrapings will be positive in up to 90% of cases of paracoccidioidomycosis with oral lesions. Distinguishing L. braziliensis from L. peruviana had for many years involved laborious culture techniques followed by electrophoretic isoenzyme analysis. Investigators at our Institute published PCR assays using both tissue as well as less invasive specimens [PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e26395; Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Jan 1;50(1):e1-6] for distinguishing the two species from cutaneous and mucosal lesions. Early identification of the species that causes the initial cutaneous infection would greatly help to prevent mucocutaneous leishmaniasis because it would allow more aggressive treatment and follow-up. In Peru, L. peruviana occurs only in the high Andes; L braziliensis occurs only in the jungle and in the Amazon. Recommended standard therapy for mucocutaneous disease is 28 days of a pentavalent antimonial (sodium stibogluconate 20mg/kg/d). In our Institute, we usually begin with amphotericin B in cases of mucosal involvement. Patients are given pre- and post-treatment hydration and supplemental potassium with daily doses given in an outpatient infusion therapy setting. Liposomal amphotericin may be used in resource-rich settings but based on limited trials it is not better in terms of efficacy even if less toxic and more convenient. Response is expected to be slow, with an 80% cure rate at the end of a 6-week course (25 mg/kg total dose) of amphotericin B 6 days per week as an outpatient. For severe refractory cases, the duration of amphotericin B is extended; therapy needs to be individualized. Our patient was treated in-hospital with oxacillin for bacterial superinfection, with improvement of pain and inflammation of the lesion. Upon discharge, he was started on amphotericin B as an outpatient and will continue to be followed up. |