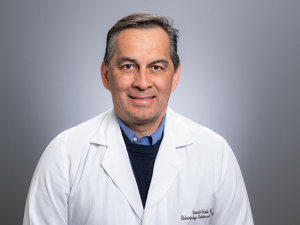

Ashita Tolwani, M.D., with a CRRT machine in UAB's Medical Intensive Care Unit. The bag at center under the machine is filled with Prismocitrate 18, the anticoagulant that Tolwani developed that is now used in continuous dialysis around the world.Florida orange growers may name an annual Citrus Queen, but UAB has the all-time Citrate Queen. That’s one of the titles — the other is CRRT Queen — bestowed by colleagues on Ashita Tolwani, M.D., an international expert on continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) and the holder of the DCI Edwin A. Rutsky, M.D., Distinguished Endowed Professorship in Nephrology in the UAB Division of Nephrology.

Ashita Tolwani, M.D., with a CRRT machine in UAB's Medical Intensive Care Unit. The bag at center under the machine is filled with Prismocitrate 18, the anticoagulant that Tolwani developed that is now used in continuous dialysis around the world.Florida orange growers may name an annual Citrus Queen, but UAB has the all-time Citrate Queen. That’s one of the titles — the other is CRRT Queen — bestowed by colleagues on Ashita Tolwani, M.D., an international expert on continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) and the holder of the DCI Edwin A. Rutsky, M.D., Distinguished Endowed Professorship in Nephrology in the UAB Division of Nephrology.

Unlike regular dialysis, which takes 3-4 hours, continuous dialysis runs 24 hours a day and is increasingly used in intensive care units for patients with acute kidney failure because it is far gentler on the body. A 2012 article by Tolwani in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrated that CRRT provides more gentle solute (waste) and fluid removal than standard dialysis techniques. This is crucial, because the mortality rate for critically ill patients with acute kidney failure who need dialysis has been reported to be higher than 50 percent. But CRRT is also a complicated therapy that requires special expertise on the part of physicians and nurses to use properly.

Citrate is the yellowish substance you’ve seen at the bottom of the tubes your doctor’s office uses to collect blood, in order to keep that blood from coagulating, or clotting. In 2004, Tolwani developed a new kind of anticoagulant solution based on citrate that has helped make CRRT safer and simpler, allowing it to spread worldwide. That anticoagulant, Prismocitrate 18, is now used in Europe, Canada, India, Australia, New Zealand and most of the rest of the planet. Approval from the U.S. FDA is still pending, although UAB and other U.S. hospitals formulate the compound in their pharmacies. (Meanwhile, Tolwani used royalties from sales of the anticoagulant to start an innovation fund that backs new kidney-related therapies.)

UAB has one of the busiest CRRT programs in the world. “We provide more than 6,000 patient-days of treatment each year,” Tolwani said. She had so many requests from other physicians wanting to learn her techniques that she started an annual training symposium at UAB that attracts doctors throughout the United States, Mexico, India and other countries and runs a constant waiting list.

| “Continuous renal replacement therapy is a special type of dialysis that we do for unstable patients in the ICU whose bodies cannot tolerate regular dialysis. Instead of doing it over four hours, CRRT is done 24 hours a day to slowly and continuously clean out the waste products and fluid from the patient.” |

CRRT is becoming more familiar to doctors and patients alike. “I’m constantly getting email from both critical care and kidney doctors around the world,” Tolwani said. So we asked her to explain the therapy, when it is used and the most common questions she hears from patients and families.

How do you explain continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) to your patients?

Continuous renal replacement therapy is a special type of dialysis that we do for unstable patients in the ICU whose bodies cannot tolerate regular dialysis. It is a very different type of dialysis from the routine type that patients may be familiar with, and it requires special skills and expertise. Regular hemodialysis is meant to be mostly an outpatient procedure. It is done usually three times a week for three to four hours at a time. The flow rates used to clear waste products and remove fluid from the patient are very fast, potentially putting stress on a patient’s heart and blood pressure. If a patient already has a low or unstable blood pressure or has heart issues, he or she will not tolerate regular dialysis. CRRT is a slower type of dialysis that puts less stress on the heart. Instead of doing it over four hours, CRRT is done 24 hours a day to slowly and continuously clean out waste products and fluid from the patient. It requires special anticoagulation to keep the dialysis circuit from clotting.

Who needs to be on dialysis 24 hours a day?

Today we can keep patients alive longer with multiple medical procedures and medications which unfortunately can increase the risk of acute kidney injury (AKI). One such example is a procedure known as ECMO [a type of heart-lung bypass machine].

About 20% of patients in the hospital setting have AKI; in the ICU it’s about 65%. When patients are on ventilators or require antibiotics because they have severe infections — sepsis — or need medications to raise their blood pressure, called vasopressors, those can all cause AKI.

Up to 25% of ICU patients with AKI may require dialysis to remove waste products and fluid that build up when the kidneys are not working. The preferred choice of dialysis for these critically ill patients is CRRT. It allows doctors to give patients the fluids, nutrition, antibiotics and other medications they need without worrying about the accumulation of waste products and fluid from the failing kidneys.

How long do patients stay on continuous dialysis?

This is the most common question I get asked by patients and families. Their biggest concern is the dialysis machine and the recovery of kidney function. Maybe that’s because they have heard of dialysis and can relate to it better than the other therapies patients receive in the ICU setting.

CRRT is used until patients start showing signs of their own kidneys recovering — or until they have more stable blood pressure and can tolerate regular dialysis.

What are the signs the kidneys are recovering?

The first sign is when a patient starts making urine. Most of the patients on CRRT are unable to make urine because of their kidney failure. However, even if the patient starts making urine, the filtrating capacity of the kidney takes a longer time to recover. It can be weeks or months before the kidney is able to filter solutes and get rid of wastes.

| The UAB Division of Nephrology is one of the top renal programs in the country, ranked No. 18 nationwide according to U.S. News & World Report. The division is also home to the longest kidney-transplant chain in the nation. |

Families often ask, “How’s the creatinine doing?” Creatinine is a toxin and waste product that the kidneys remove and so a creatinine higher than the normal range indicates the kidneys are damaged and cannot filter solutes and toxins. When a patient is treated with CRRT, the machine removes waste products and toxins and so the creatinine levels become lower and in the normal range. But this does not reflect what the patient’s kidneys are doing. Therefore, I first teach families to focus on how much urine the patient is making. Once a patient is making more than 500 ml to 1,000 ml of urine a day, we can test the urine to see if it is actually filtering out the toxins, indicating that the kidneys are trying to recover. Once the kidneys are able to filter the waste products so they do not build up to dangerous levels in the body, dialysis can be discontinued.

Families will also say, “They’re not drinking anything. That’s why they’re not making urine.” I explain that once the tubules in the kidney are damaged and not working, giving more fluids isn’t going to help and can make things worse. Even if dehydration was a cause of the original injury, it’s not dehydration anymore once the tubules are damaged. Furthermore, patients are still getting fluids from intravenous medications and nutrition. If the kidneys have shut down, the excess fluid has nowhere to go and accumulates in the body leading to fluid in the lungs, swelling of the body and even heart issues.

| To request an appointment or find a provider, visit uabmedicine.org. |

It may take three months or longer to recover from acute renal failure. If you have healthy kidneys before entering the hospital, you have a greater than 90% chance of recovering. If you already have chronic kidney damage, you are less likely to recover.

So how can I keep my kidneys healthy?

I always tell my patients to stay hydrated. Many medications that are normally safe become dangerous to your kidneys when you are dehydrated and the blood supply to the kidneys decreases. Examples are ACE inhibitors and ARBs, two common heart medications used for blood pressure control and both heart and kidney issues.

If you are dehydrated, even something as simple as ibuprofen can shut down your kidneys. Many medical conditions such as high blood pressure and poorly controlled diabetes can permanently damage the kidneys as well. As a result, it is very important to keep high blood pressure and diabetes controlled.

What else do your patients or families want to know?

Family members always ask, “Can I just give my kidney right now for a transplant?” Unfortunately, in the state the patient is in to be in the ICU, they would not survive a transplant operation. I tell them, “If they don’t get their kidney function back in three months, then we’ll consider kidney transplantation. Right now, they need to recover.”

You also do research on CRRT — what are the questions that need to be answered?

Because we have so much experience with CRRT at UAB, we help set what the research agenda should be. Right now, that is looking at the most appropriate dose of CRRT and early versus late initiation of the therapy.