Imagine. You wake up in your bed on a warm, spring morning. Grey early morning sunlight filters through the blinds and your nose pick up on the smell of freshly brewed coffee. But, something is wrong. Your body, particularly your hands, wrists, and ankles, are in excruciating pain. You call a loved one to help you out of bed, even to brush your teeth. This is what life is like for someone experiencing severe rheumatoid arthritis.

Vishal Sharma, Ph.D. candidate in the Immunology theme of the Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology department at UAB, begins his Discoveries talk with this imagination-based simulation. His research focuses on how T cells get “turned on” and “turned off” throughout the course of an individual’s experience of RA. But before Sharma gets into the details of his research, he gives us a rundown of what rheumatoid arthritis is and why further research on the disease is needed.

Vishal Sharma, Ph.D. candidate in the Immunology theme of the Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology department at UAB, begins his Discoveries talk with this imagination-based simulation. His research focuses on how T cells get “turned on” and “turned off” throughout the course of an individual’s experience of RA. But before Sharma gets into the details of his research, he gives us a rundown of what rheumatoid arthritis is and why further research on the disease is needed.

Many of us are somewhat aware of RA (rheumatoid arthritis) and its symptoms. This makes sense, as RA has been around for a long time. There is evidence of its appearance in human society even as far back as the 15th century. However, we are not all aware that RA is actually an autoimmune disease. This means that RA occurs because the body’s own immune system mistakes healthy cells in the body for enemy cells and begins to fight them. In the case of RA, the immune system recruits cells in the membranes of “movable” joints, such as the hand, wrist and finger joints, causing the membrane to swell and joint fluids to decrease. This causes the bones that are connected at this joint to grind on each other. Naturally, this can cause a lot of pain, and even keep you from getting out of bed on your own on a spring morning.

With all that is known about RA, scientists and medical professionals are interested in learning to treat RA even more effectively. However, there is still a lot for scientists to learn in order to do so. For example, scientists do not yet know what causes the onset of RA and, thus, are unsure of how to prevent it. And while treatments have been developed for RA – and for these treatments, many patients with RA are grateful – there are still improvements that can be made. Currently, only 10 percent to 40 percent of U.S. patients with RA experience full remission. It is research like Sharma’s that could one day translate into new medicines and practices that could raise that percentage to 100.

With all that is known about RA, scientists and medical professionals are interested in learning to treat RA even more effectively. However, there is still a lot for scientists to learn in order to do so. For example, scientists do not yet know what causes the onset of RA and, thus, are unsure of how to prevent it. And while treatments have been developed for RA – and for these treatments, many patients with RA are grateful – there are still improvements that can be made. Currently, only 10 percent to 40 percent of U.S. patients with RA experience full remission. It is research like Sharma’s that could one day translate into new medicines and practices that could raise that percentage to 100.

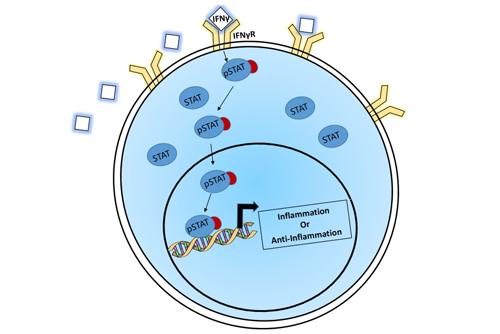

So, what exactly is Sharma researching? He is interested in T cells. These cells show up in movable joints where people are experiencing the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. They have two responses, either to create inflammation by releasing protein that aids in bone damage or to suppress inflammation by releasing proteins that halt the disease in its course. The bifurcation of this response is dependent on the individual cell. Previous data in the field has shown that a gene named IFNgR (interferon gamma receptor) was upregulated in patients that had RA compared to those who didn’t.

When the body makes IFNgR into a protein, this protein is then attached onto the cell’s surface. During the right kind of stimulation, the cell turns on a protein (pSTAT1) that binds onto the DNA and activates genes. This causes the cell to behave in one of two ways: inflammatory or anti-inflammatory. The previous data (mentioned above) suggested to Sharma that this gene, when turned into a protein, could be aiding in the destruction caused by RA. Surprisingly, he has found that when this protein is stimulated, its downstream activator (pSTAT1) is higher in patients in remission rather than those inactive disease. This would suggest to Sharma that perhaps in RA, this protein (if functioning properly) has protective roles rather than damaging roles.

Such research could hold the key to identifying biomarkers that signal when a patient with RA needs nontraditional treatment for their symptoms. This could go a long way toward improving remission rates for patients with RA in the U.S. It is already known that early and aggressive treatment is key to improving a patient’s chances for experiencing remission. If a biomarker is identified that allows doctors to prescribe more personalized treatment earlier in the process, medical professionals do not need to spend time determining what approach will work for a particular patient through trial and error. Instead, they can run a quick test to look at levels of a particular biomarker in the patient’s body and use the results to decide on an effective treatment plan in the initial stages.

Such research could hold the key to identifying biomarkers that signal when a patient with RA needs nontraditional treatment for their symptoms. This could go a long way toward improving remission rates for patients with RA in the U.S. It is already known that early and aggressive treatment is key to improving a patient’s chances for experiencing remission. If a biomarker is identified that allows doctors to prescribe more personalized treatment earlier in the process, medical professionals do not need to spend time determining what approach will work for a particular patient through trial and error. Instead, they can run a quick test to look at levels of a particular biomarker in the patient’s body and use the results to decide on an effective treatment plan in the initial stages.

Sharma’s research on T cells could provide the key to one day having such effective tests and treatments to offer patients with RA, so we can all leap out of bed in the morning without pain.