|

Gorgas Case 2017-06 |

|

|

The patient was seen on the wards of the Cusco Regional Hospital.

History: 44 year-old female presented to the outpatient clinic complaining of a 2-week history of 2 cm itchy migratory subcutaneous nodule initially arising over the epigastric region. She had earlier presented to another hospital with right upper quadrant pain. Over the next 2 weeks, the lesion migrated towards the left breast and the patient was admitted to undergo excision of the lesion. She denied having cough, fevers, weight loss or other constitutional symptoms.

Epidemiology: Born and lives in Cusco city where she works in an office. Wears shoes and doesn't swim. Her diet includes mainly green leafy vegetables and fresh vegetables and herbal extracts. Admits eating ceviche occasionally. No known TB exposure or specific HIV risk factors. Has a healthy child at home. Physical Examination: Normal vital signs, afebrile. Chest: Breath sounds were present bilaterally, no wheezing or crackles. Heart: RRR, no murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Abdomen: Bowel sounds were present, the abdomen was soft, non-tender without hepatosplenomegaly. Skin: 3-cm nodule at the inferior border of the left breast, slightly tender to palpation, mobile and hyperpigmented. Several hyperpigmented macules in the epigastrium and left upper quadrant (Image A). No lymphadenopathy. Rest of the exam was unremarkable. Laboratory: WBC 7.5 (50 neutrophils, 17 eos, 6 monos, 26 lymphs). Hb 11.8, Hct 38, MCV 76.2, MCH 24.2. Platelets 220, 000. Glucose 87. Renal and liver function were normal. Ultrasound of the liver 2 weeks before admission is shown (Image B).

UPCH Case Editors: Carlos Seas, Clinical Course Coordinator / Sofia Zavala, Associate Coordinator UAB Case Editor: David O. Freedman, Course Director Emeritus / German Henostroza, Course Director |

|

Diagnosis: Fasciola hepatica, chronic form with ectopic cutaneous lesion. Parenchymal form.

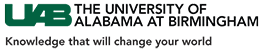

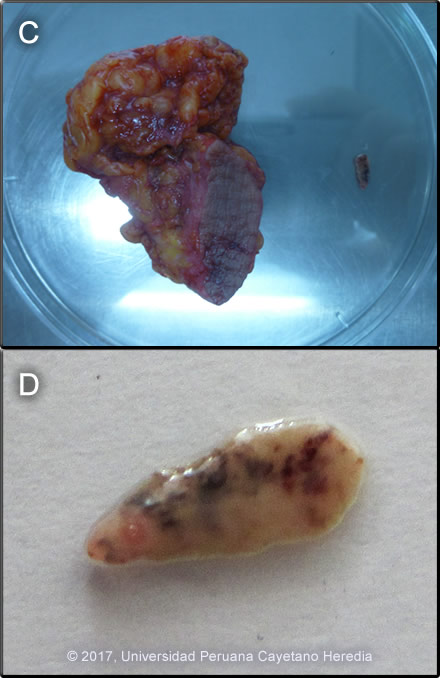

Discussion:The liver ultrasound (Image B) shows intra-hepatic bile duct dilatation. During an ERCP, 3 adult Fasciola hepatica parasites were removed. Her stools were positive for ova of F. hepatica. The nodule was excised (Image C) and a juvenile F. hepatica was found in the adjacent tissue (Image D). See case 2015-05 for histologic demonstration of this parasite. Of note, her husband was diagnosed with acute fascioliasis 3 months earlier and was treated with triclabendazole. She had been treated at the same time with 2 courses of triclabendazole but her stools had remained positive prior to the ERCP. Fasciola hepatica is a trematode (fluke or flatworm) zoonosis in which the adult parasites inhabit the large biliary ducts of their definitive host. As with all other trematodes, Fasciola hepatica requires a snail intermediate host. Eggs produced by the hermaphroditic adults pass with the feces and hatch, releasing larvae in fresh water. After passing through a snail, mature cercariae emerge and rapidly encyst on various kinds of aquatic vegetation such as watercress or alfalfa. Recent data, however, also suggests waterborne transmission. After ingestion by a human or animal definitive host, the metacercariae excyst in the duodenum and larvae penetrate the intestinal wall and subsequently migrate directly into the liver via Glisson’s capsule and embark on a destructive migratory process through the hepatic parenchyma for 3 to 4 months until they reach large biliary ducts, where they then mature to adults. The mature adults are from 1 to 3 cm long and attach to the biliary epithelium by a single ventral sucker. Direct visualization of adult forms is uncommon, however characteristic eggs can be seen on stool examination. Patients who present in the early migratory phases of infection prior to maturation of the worm do not pass eggs in the stool. Specific serology is the test of choice in these acute cases, but most tests are produced from crude antigens and have significant results variability. The distribution of F. hepatica is cosmopolitan, but is by far the most common in cattle-raising areas where herbivores are common definitive hosts. Other important definitive hosts are goats, sheep, horses, llamas, vicunas, and camels. The Altiplano regions of the Peruvian and Bolivian Andes are highly endemic, with human prevalence rates as high as 67% in some villages. In the agricultural areas near Cusco, the prevalence in children 3 to 12 years old is 11% by stool microscopy and Fas2 ELISA [Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014 Nov;91(5):989-93]. Egypt, Cuba, and Northern Iran are also highly endemic and the parasite is emerging in Vietnam and Cambodia. Cooking, which would kill the metacercariae, dramatically changes the flavor of watercress especially and the population is reluctant to adopt this simple measure. Emoliente, a local tea-like drink that uses drops of watercress juice to provide a bitter flavor is a frequent vehicle of infection. The differential diagnosis of eosinophilia with migrating paniculitis includes gnathostomiasis, paragonimiasis, loiasis, and cutaneous larva migrans. Toxocariasis causes hypereosinophilia with hepatomegaly but the pathology results from small granulomas around individual non-migrating larvae and not the large destructive lesions seen in our patient. Paragonimiasis, loaisis, and cutaneous larva migrans are not reported in Cusco city. Gnatosthomiasis has been diagnosed in Cusco before, but fascioliasis is far more common in the area. Migratory subcutaneous nodules in fascioliasis are uncommon, but the diagnosis should be suspected in subjects from endemic areas presenting with eosinophilia. |