Case history:

238g (409 - 589 g) placenta w 3-vessel UC from delivery of IUGR briefly viable infant at 38.6 wkG. Maternal hx: IgM + for HSV 1 & 2; IgG+ for HSV2. No travel hx but patient makes her own yogurt.

Which of the following is the correct diagnosis for the placental pathology?

- Herpes Simplex Virus villitis

- Massive chronic intervillositis

- High grade diffuse chronic villitis of unknown etiology with vascular obliteration and avascular villi

- Toxoplasma gondii villitis

- Listeria monocytogenes

Answer: C

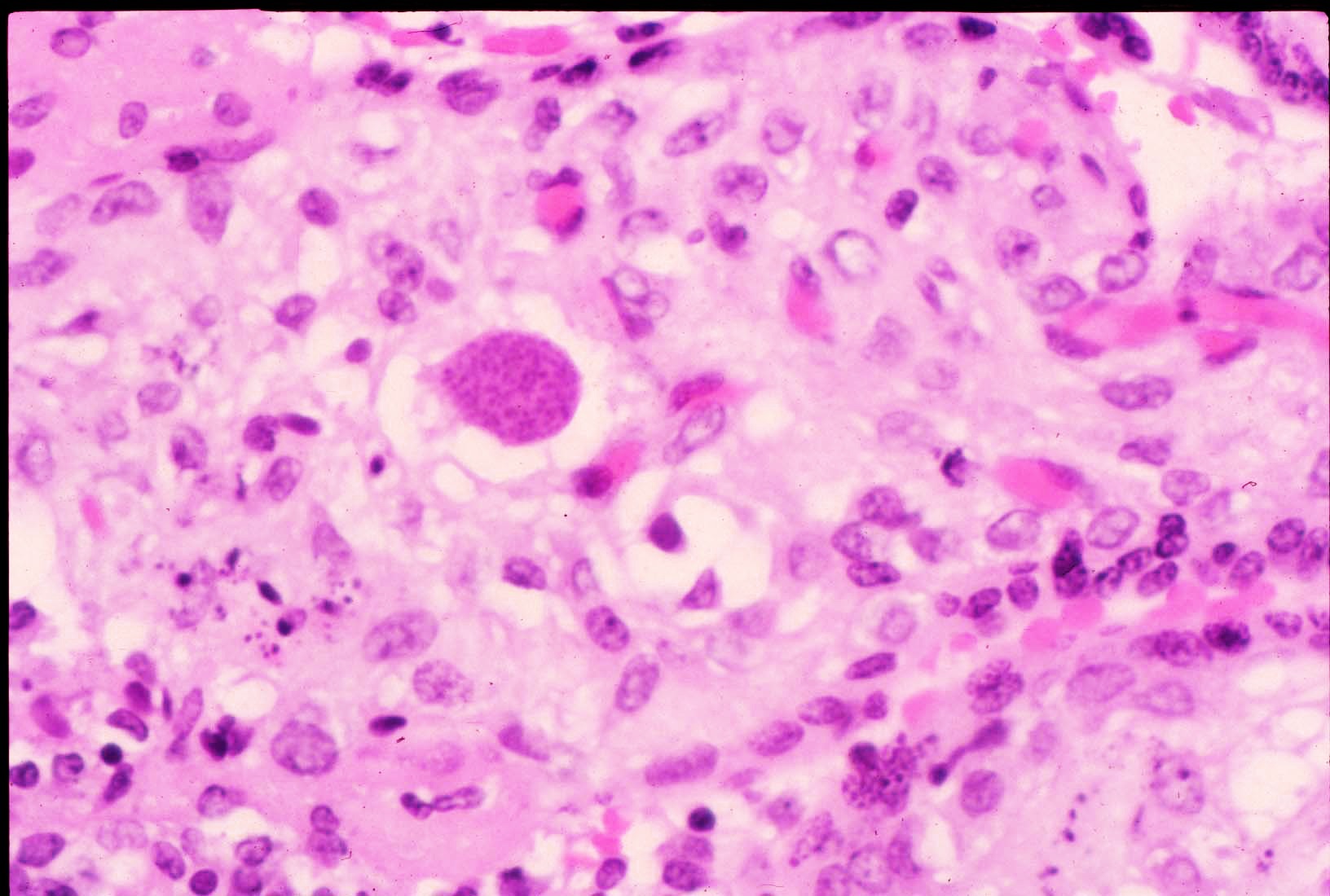

FIG 3a arrow DIFFUSE HIGRD VUE w STEM V VASCULITIS HI POW

FIG 3a arrow DIFFUSE HIGRD VUE w STEM V VASCULITIS HI POW  fig 4 DIFFUSE HIGRD VUE w STEM V VASCULITIS MEDPOW

fig 4 DIFFUSE HIGRD VUE w STEM V VASCULITIS MEDPOW  FIG 5 VUE HP KARORRHEXIS EARLY CHNG

FIG 5 VUE HP KARORRHEXIS EARLY CHNG FIG 6 LP INFILTRATE IN DECID BASAL HIPOW

FIG 6 LP INFILTRATE IN DECID BASAL HIPOW  FIG 7 chronic chorio 2

FIG 7 chronic chorio 2  FIG 8 hsv 1a

FIG 8 hsv 1a FIG 9 hsv 1

FIG 9 hsv 1  FIG 10 hsv immuno pos

FIG 10 hsv immuno pos  FIG 11 40x Toxo 1a 2

FIG 11 40x Toxo 1a 2 FIG 12 Toxo in Chorionic villus

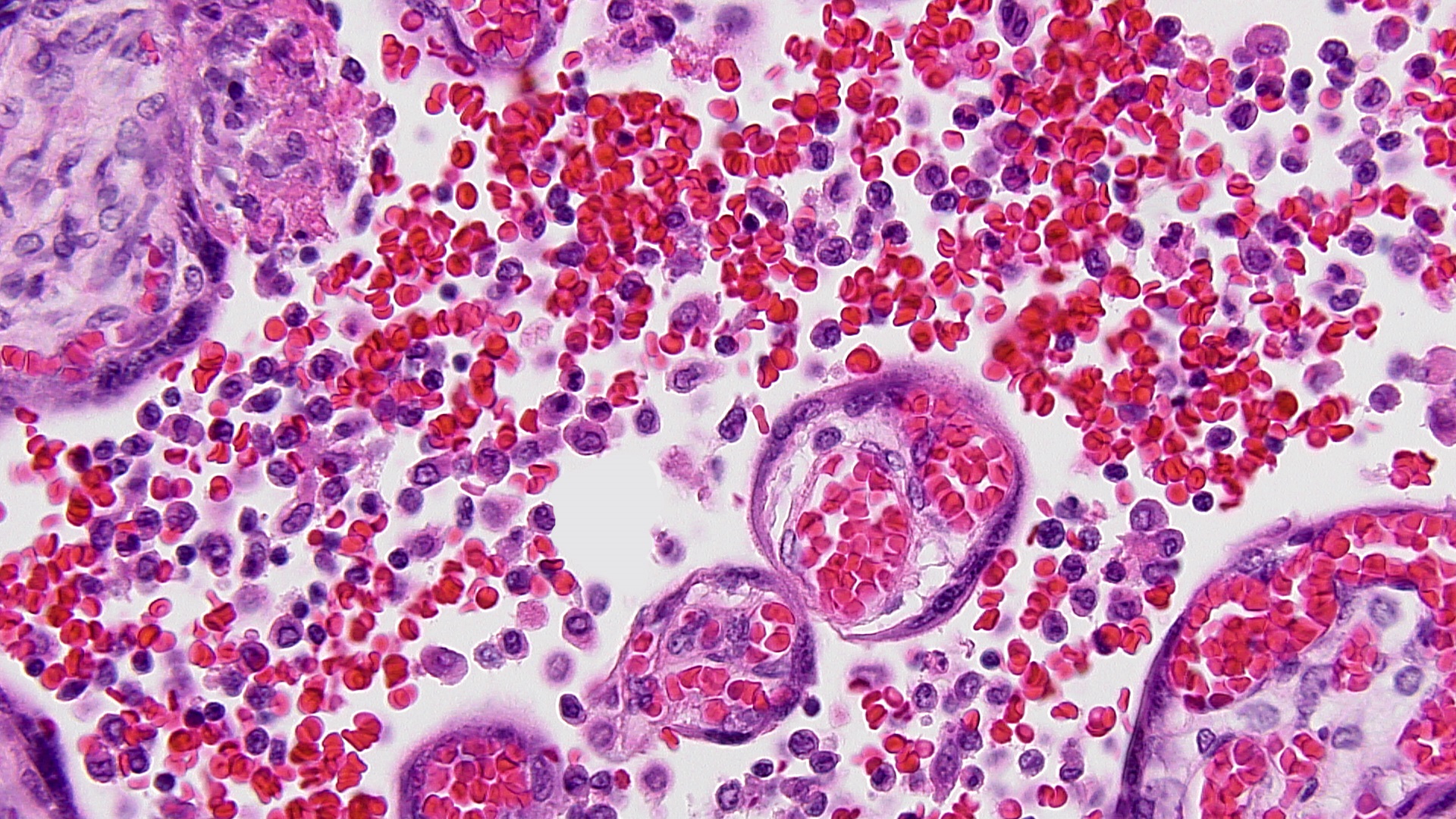

FIG 12 Toxo in Chorionic villus  FIG 13 MCI HP

FIG 13 MCI HP

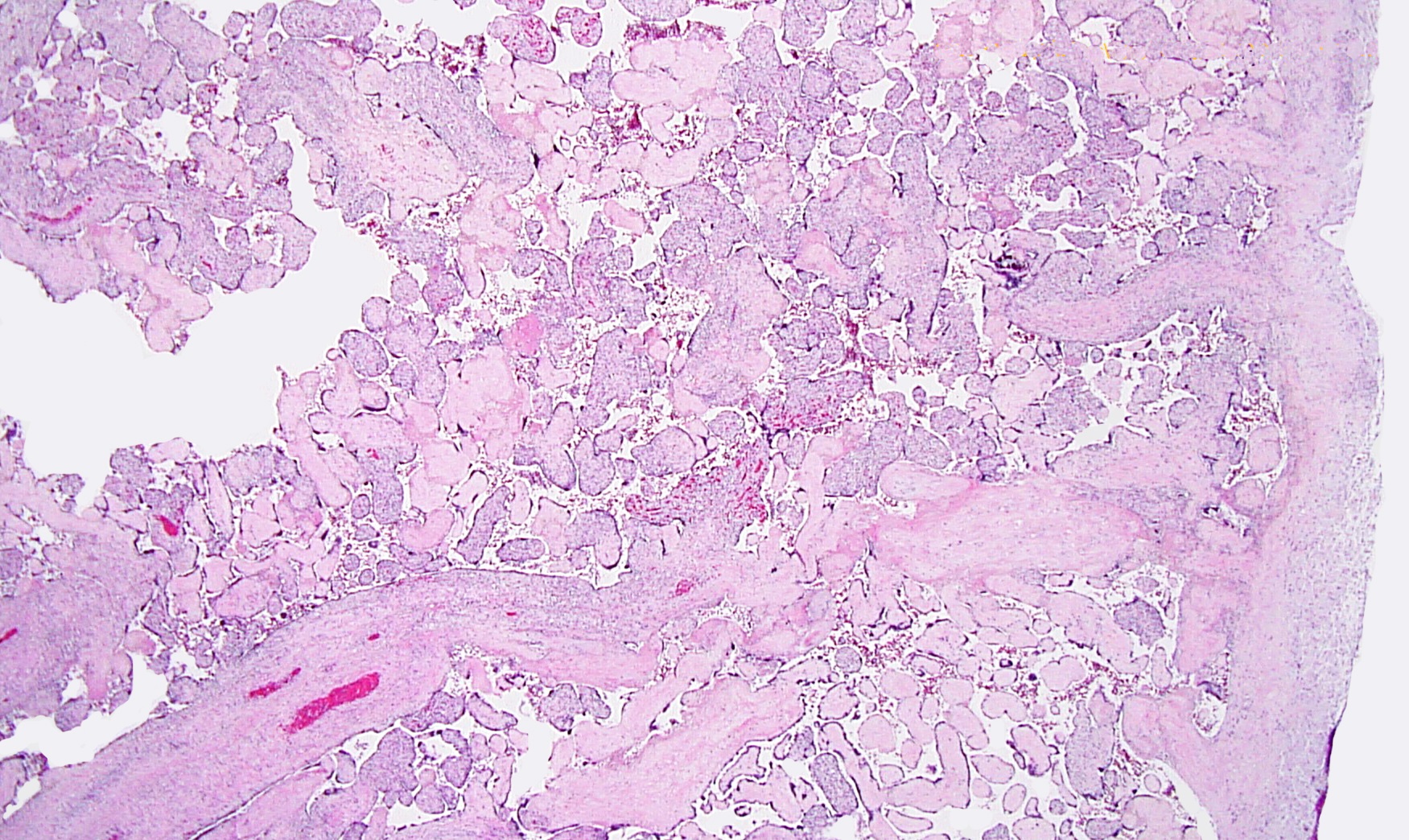

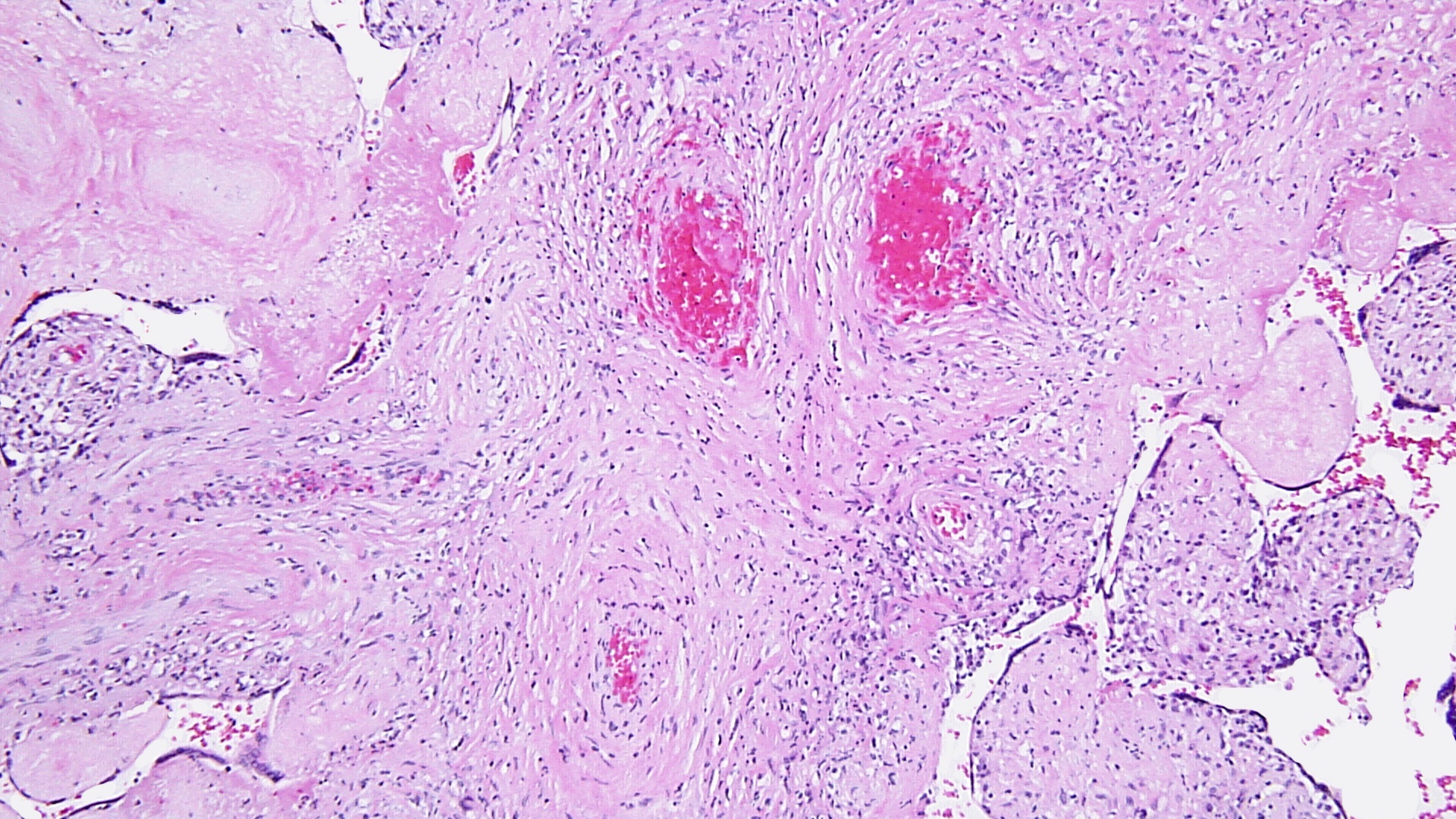

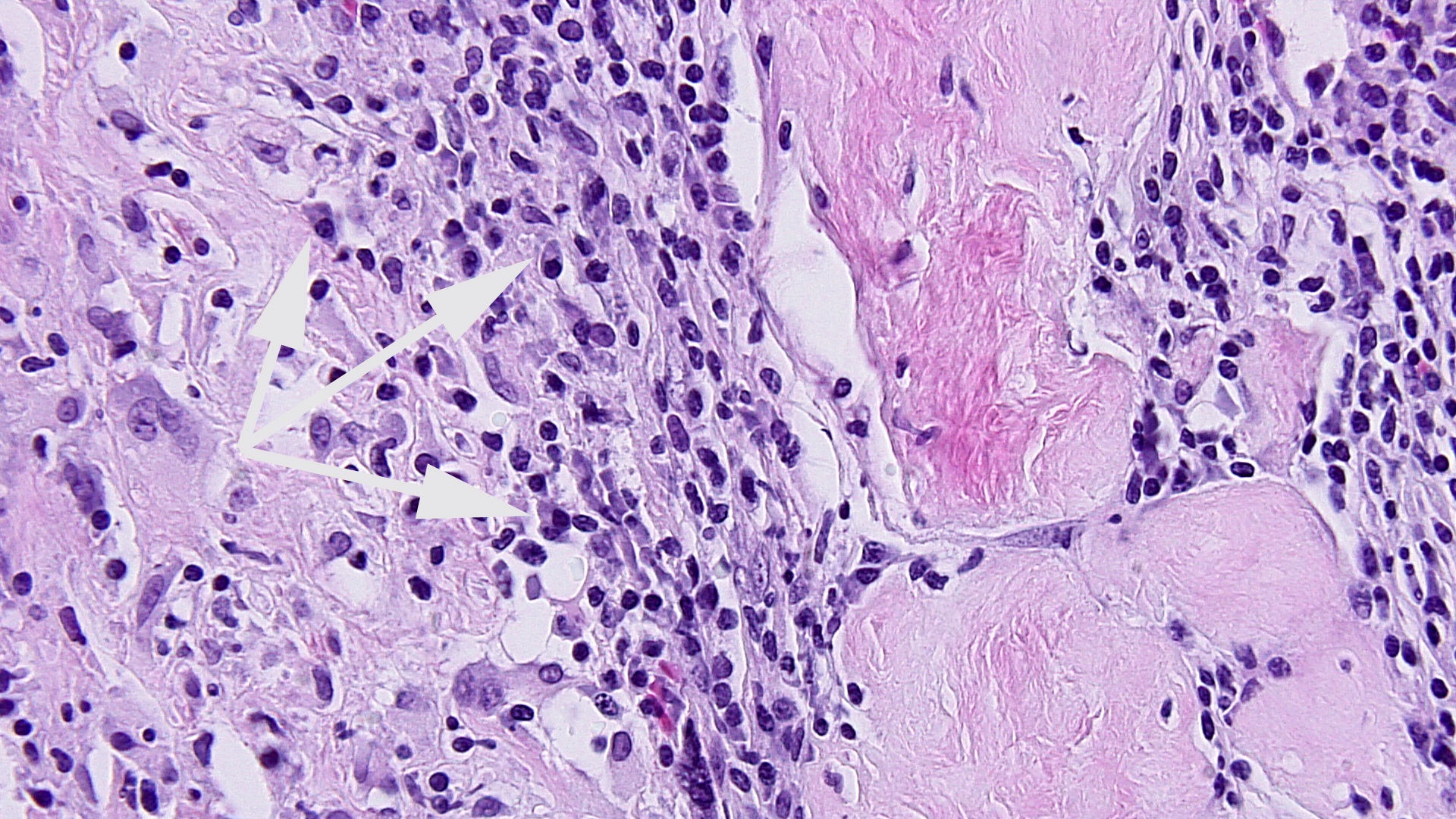

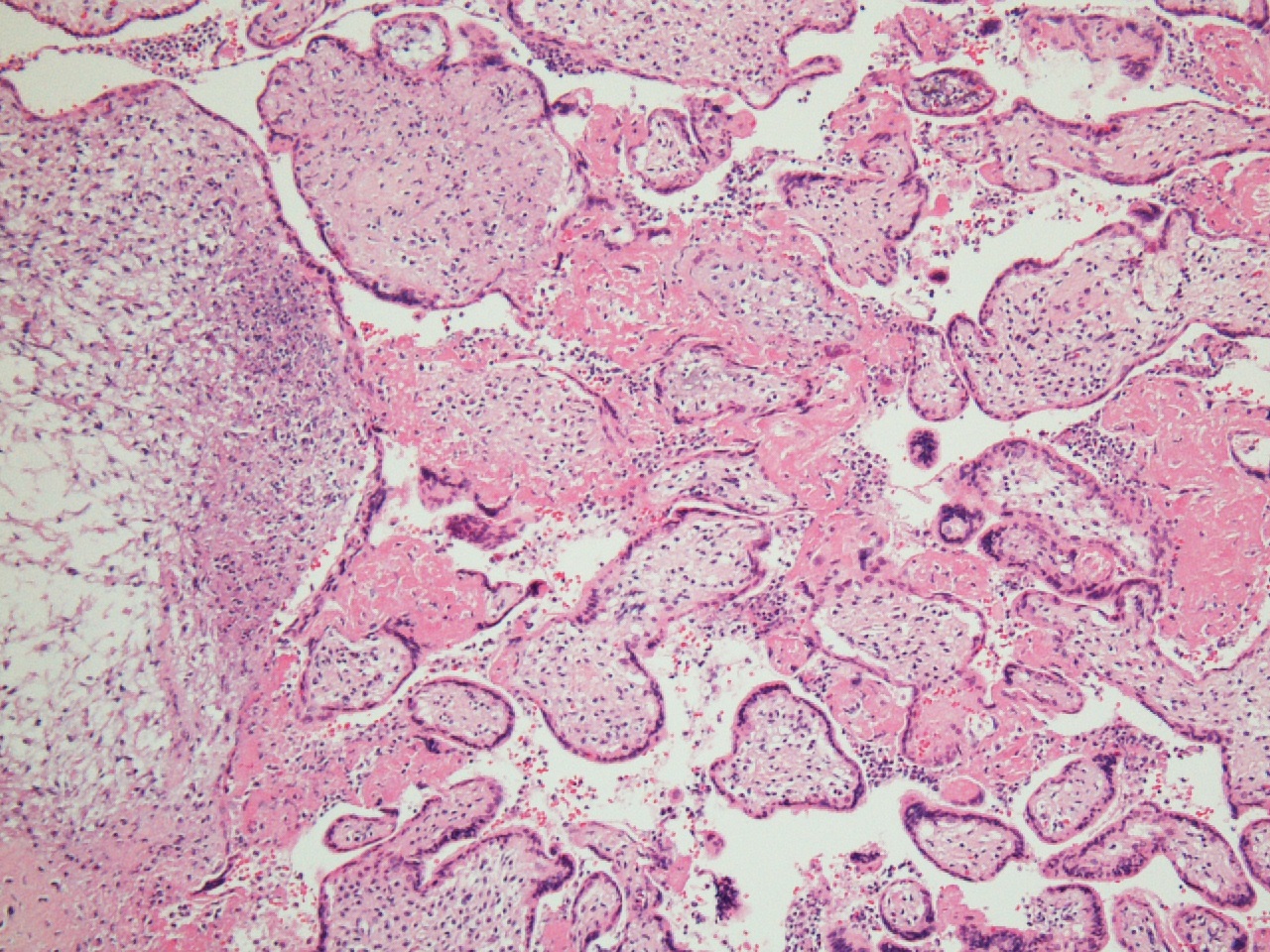

Figs 1,2 show severe chronic villitis of unknown etiology (VUE) characterized by lymphohistiocytic villitis. This case also shows stem villous perivasculitis and obliteration of stem villous vessels (Fig 3) and several large areas of sclerotic distal villi seen in Fig 1 as clusters of pale pink ghostlike remnants of villi.

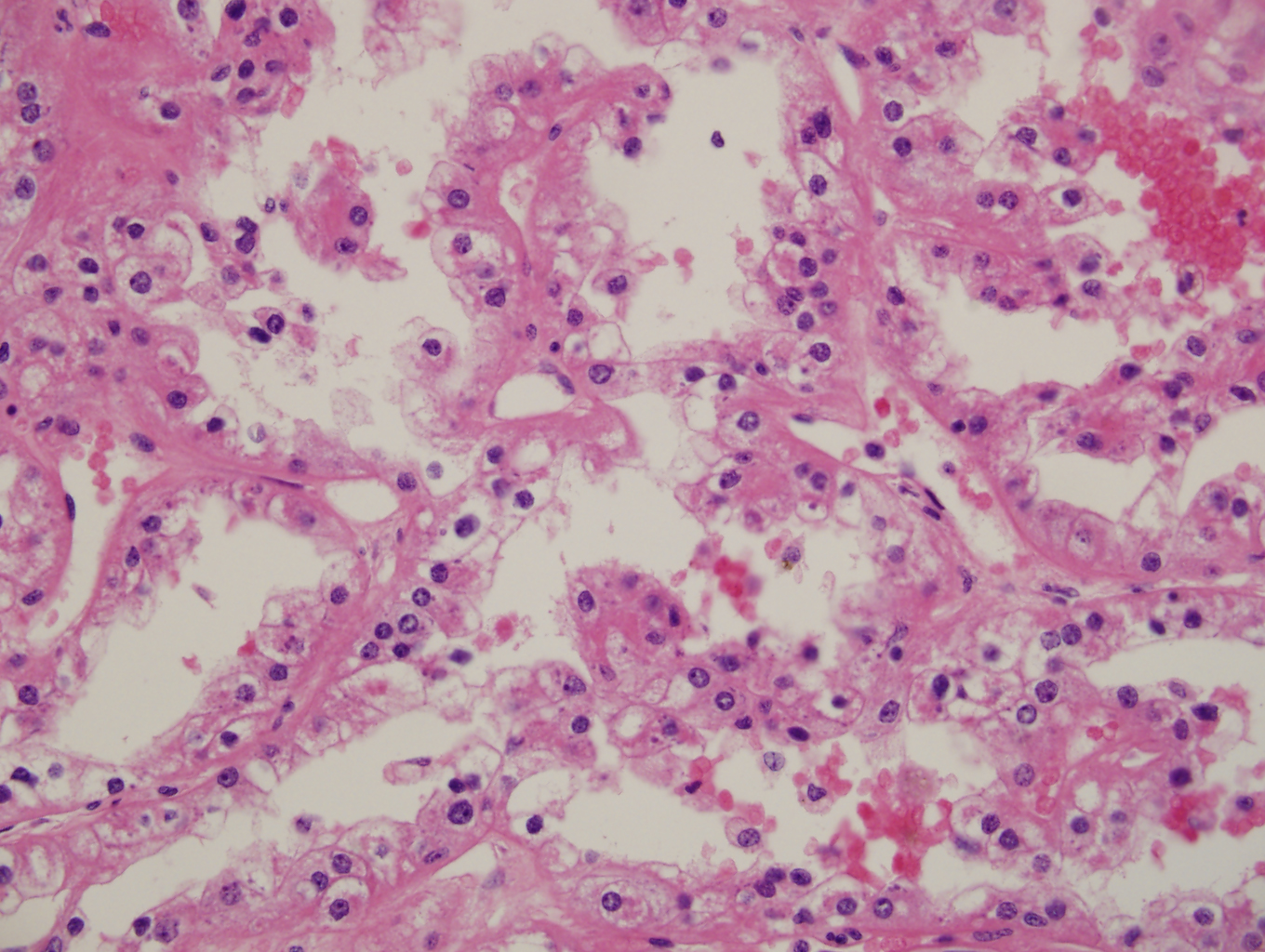

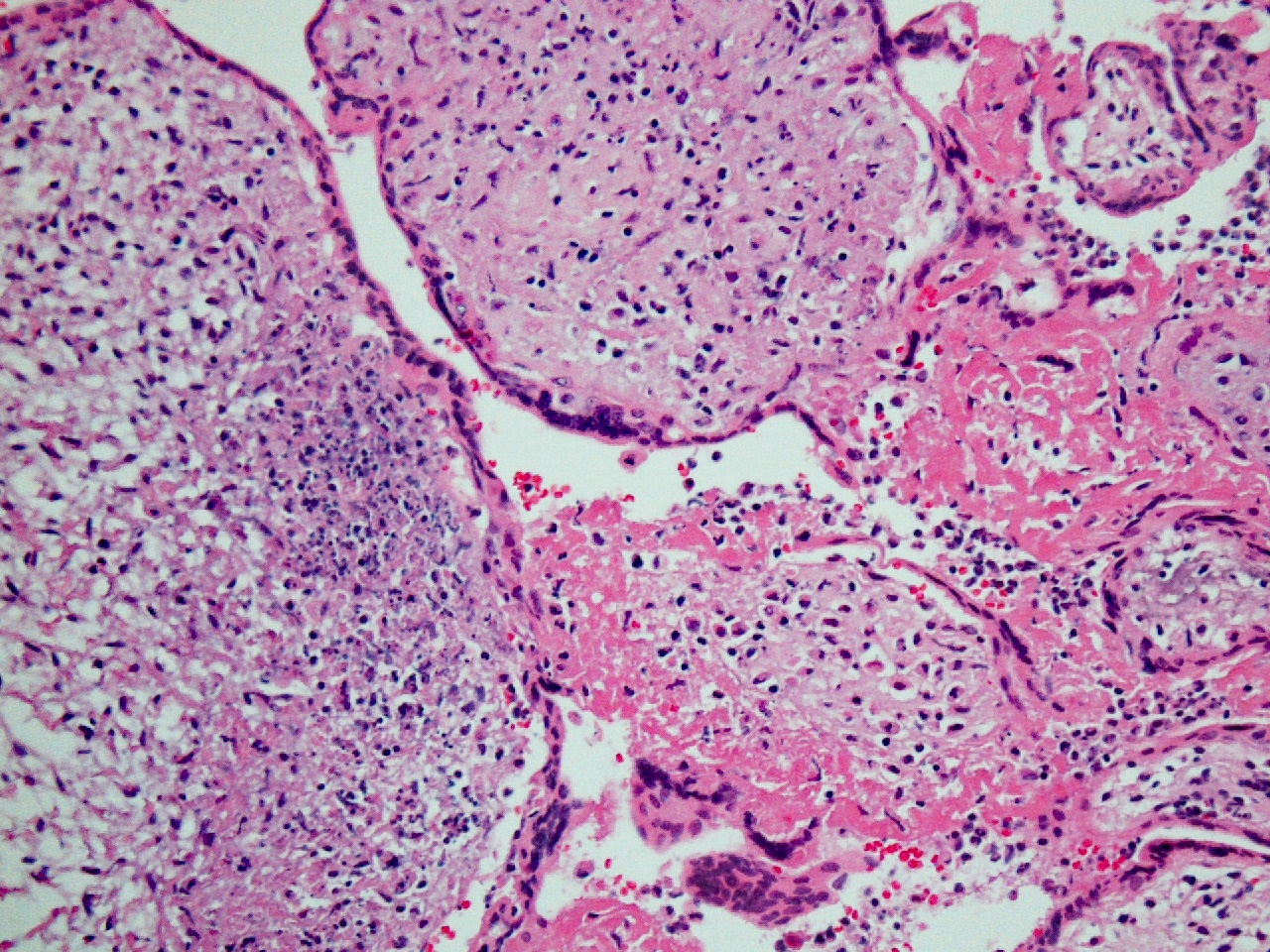

The inflammation is high grade (≥10 contiguous villi with lymphohistiocytic villitis in multiple foci on 1 slide) with aggregation of densely cellular villi and diffuse (≥30% villi affected.) (See Figs 3-5) This lesion is associated with high rates of fetal intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) (42%), fetal death, and a recurrence risk of at least 34%. The villous stromal lymphocytic infiltrates are T lymphocytes of maternal in origin [CD3+, CD8+>>CD4+, syncytiotrophoblast ICAM-1+ and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) activation+, CD45RB+>>, C45RO+; CD20-, CD138-, PAX53-] and the chorionic villous histiocytes (Hofbauer cells) are of fetal origin (CD68+) There is strong evidence this process represents maternal alloimmune reaction to the fetal hemiallograft.

The maternal T-lymphocytes infiltrate the villi and result in activation of the Hofbauer cells and cytokine production with cytokine elevation in the fetus. There is villous destruction and loss of functional villous surface for exchange which likely results in fetal IUGR, hypoxia, and Doppler arterial blood flow abnormalities on ultrasonogram interrogation of umbilical arterial blood flow; the lesions and loss of villous vascularity result in increased resistance to blood flow in the villous tree. Studies have shown that significant risks for perinatal morbidity and mortality occur with high grade and diffuse lesions and the additional loss of blood flow in the stem villi further compromises the villous tree.

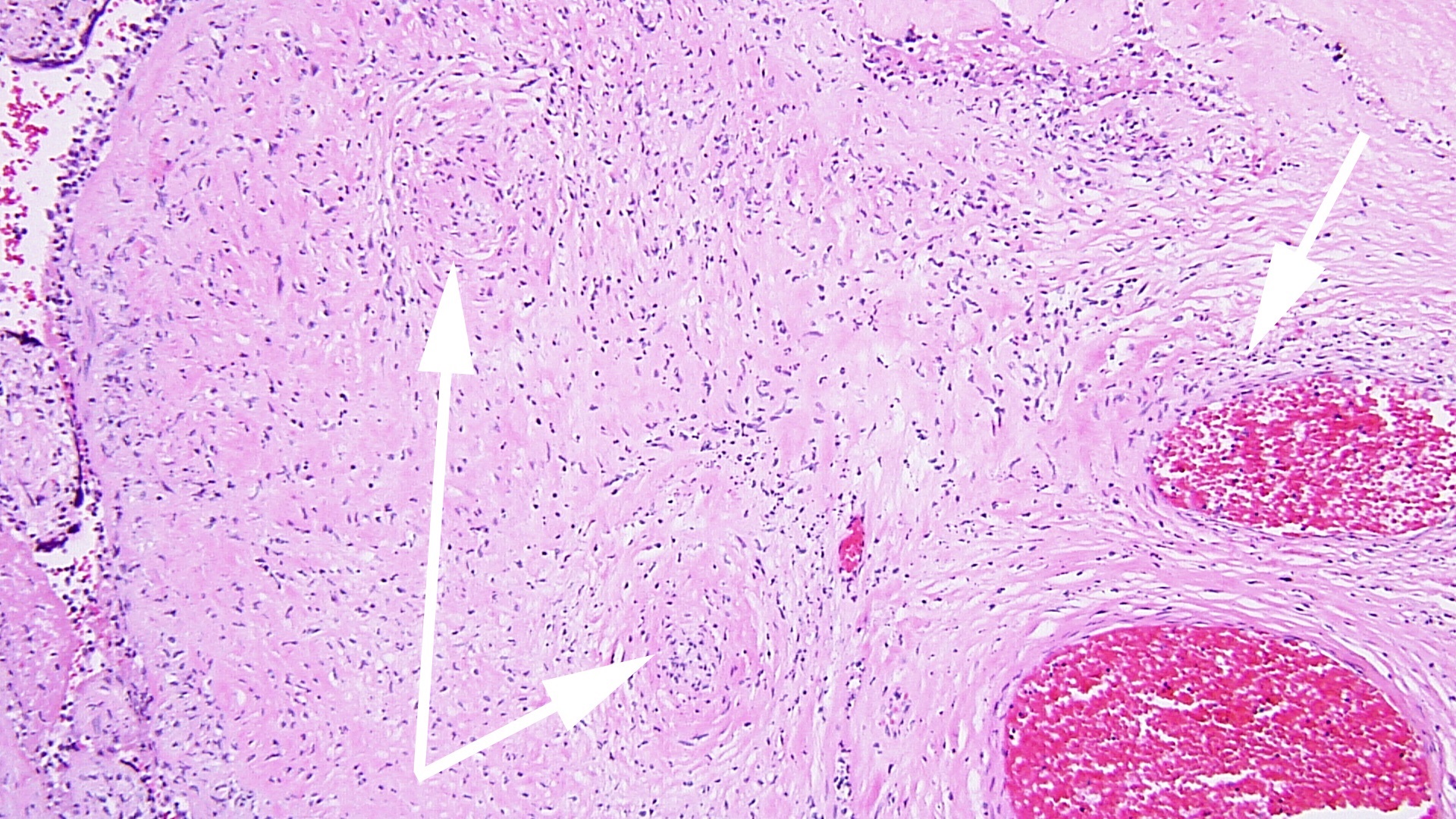

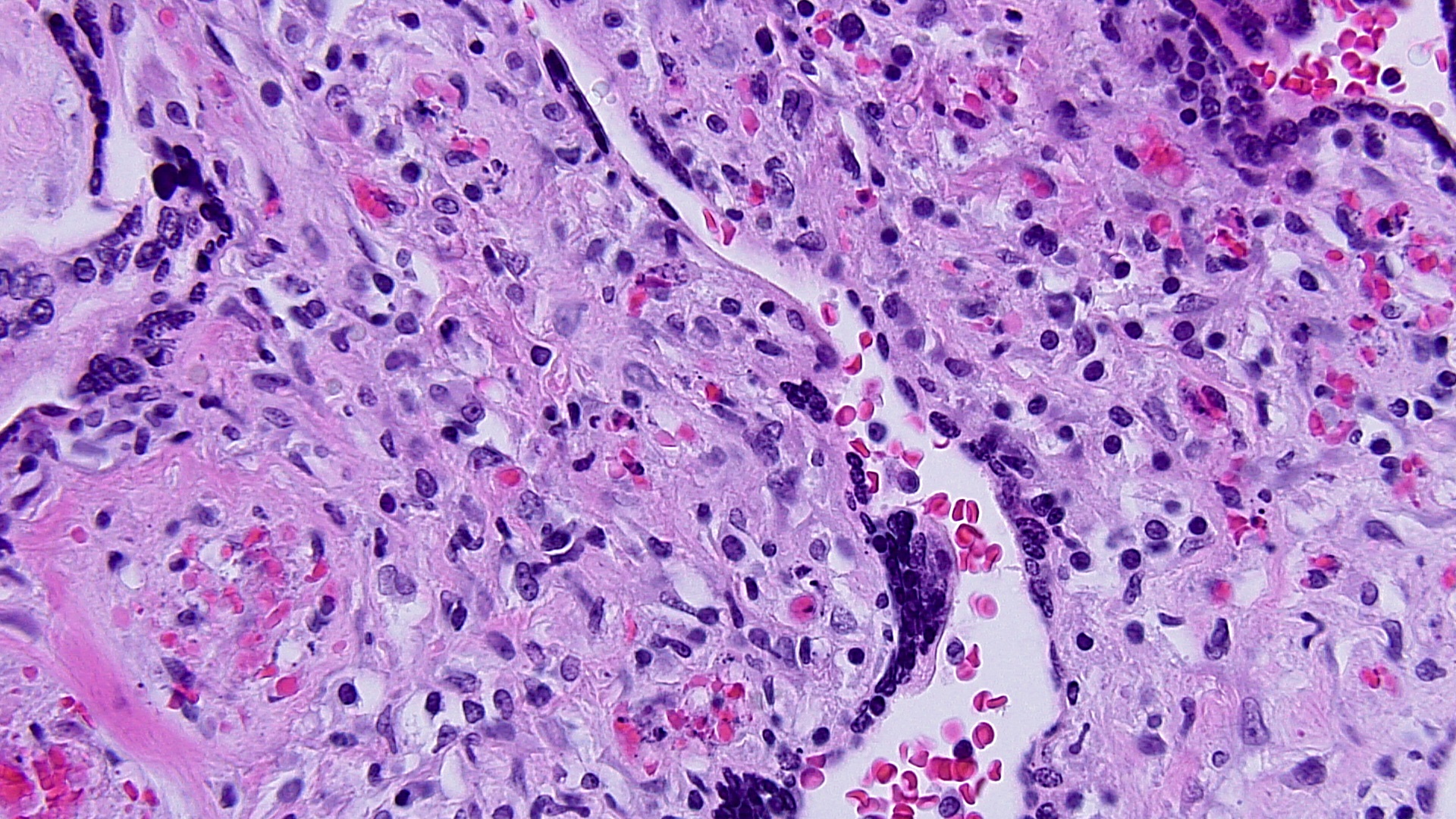

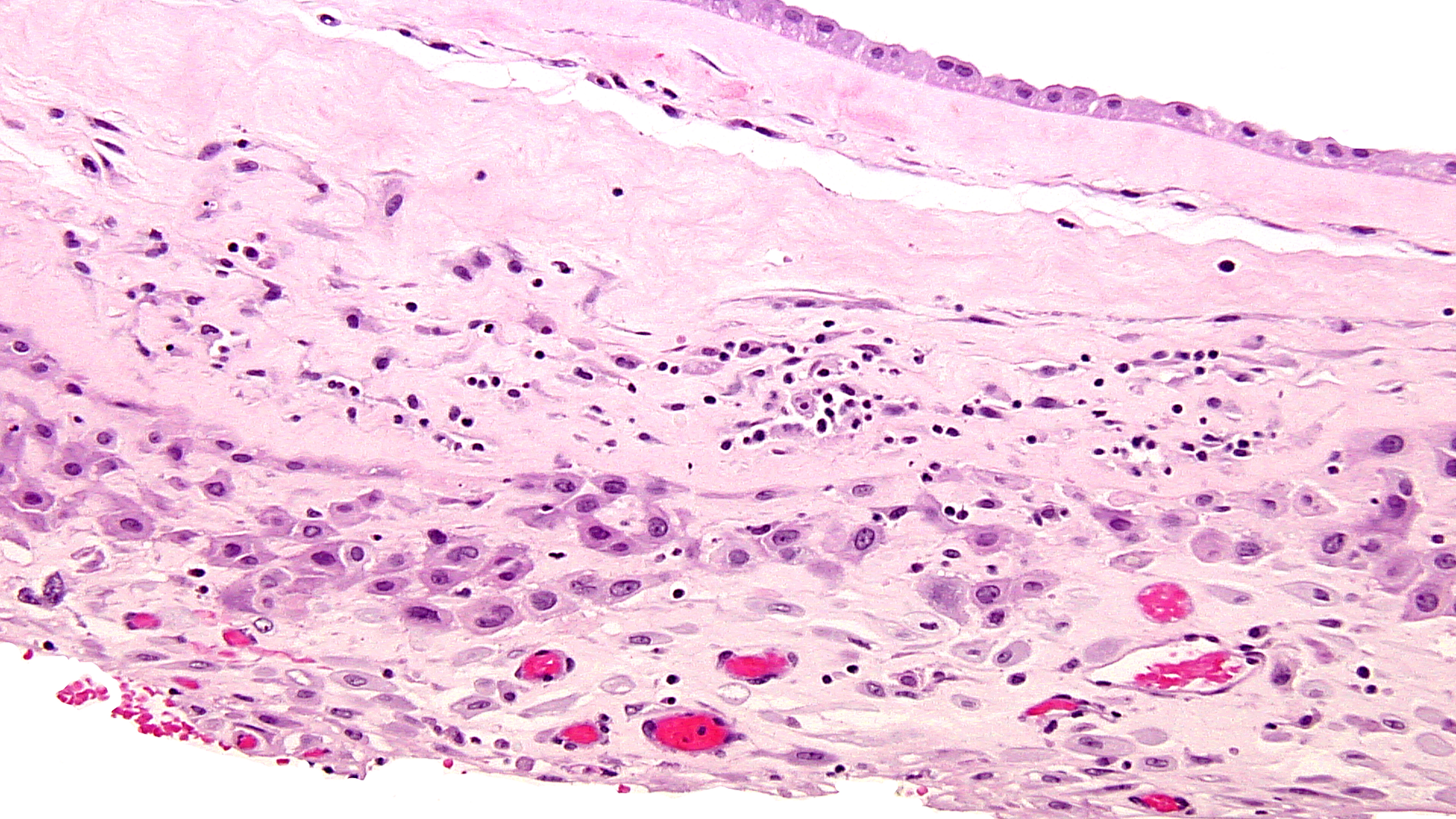

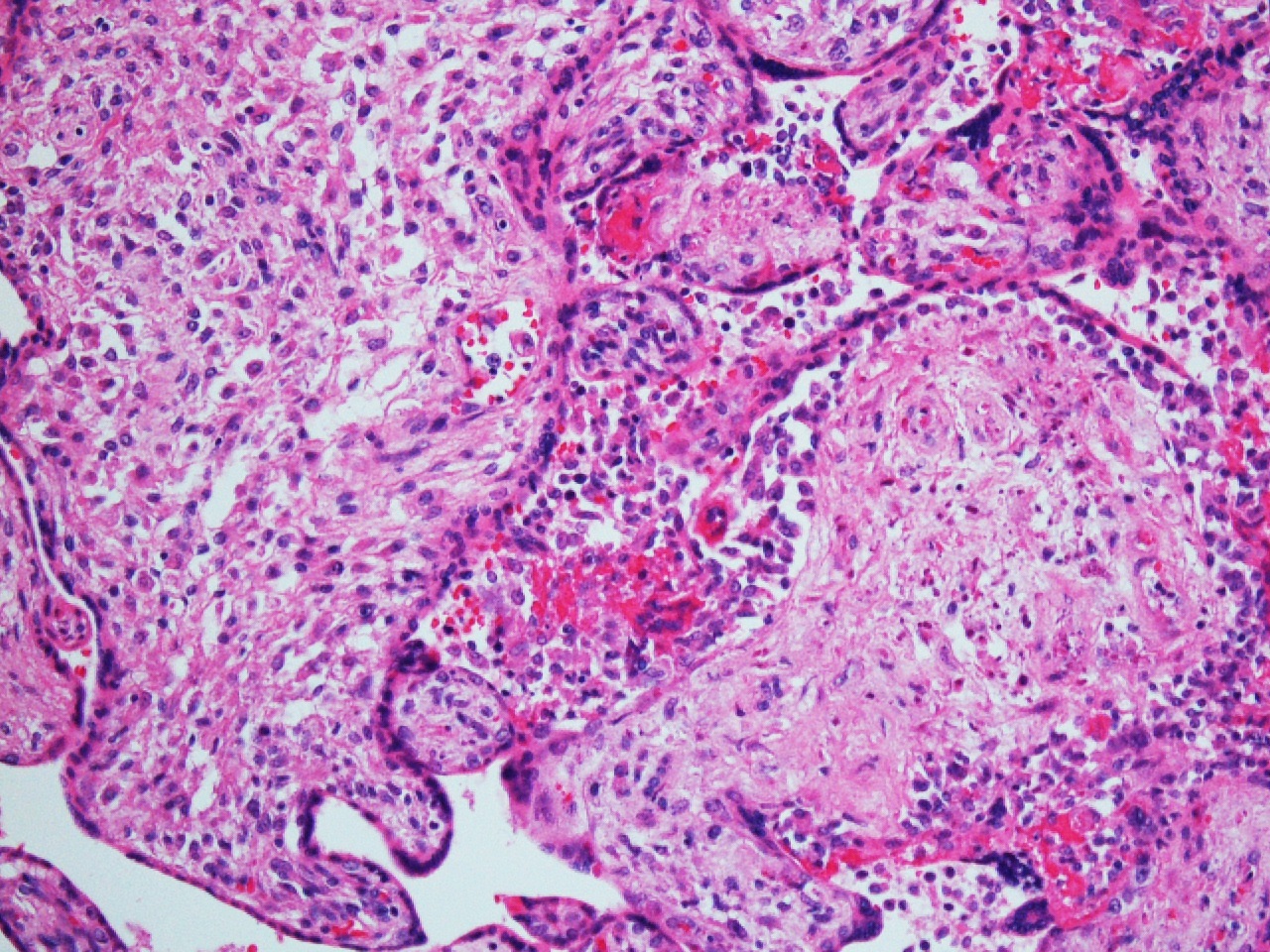

Villous destruction with VUE can result in terminal villous sclerosis (Fig 2) but the large segmental areas of villous avascularity, as seen in this case, are due to thrombosis and involution of blood vessels in stem villi (Fig 3a) with arrows denoting perivasculitis and round foci of involuted vessels. (see also Fig 4) The villi in this case show extravasation of fetal red blood cells into the vessel walls and villous stroma, secondary to hypoxia and damage to the endothelial cells of the villi (Fig 5). The lesions are typically of varying age (some are calcified; others are in earlier stages of thrombosis.) Some of the extravasations in the terminal villi could reflect involutional changes with cessation of blood flow with fetal demise (e.g., postmortem change with intrauterine retention following fetal demise), but the clinical history indicates this was an intrapartum fetal death. The decidua basalis shows lymphoplasmacytic villitis (Fig 6), and chronic lymphocytic chorionitis is not uncommon with VUE (FIG 7).

The pathology in this case so diffuse that infection was a strong concern, especially with the history of HSV infection. The woman had no lesions, was asymptomatic, and denied any systemic symptoms and was afebrile on admission. She had not been sick or exposed to individuals with infections. (A) HSV results in a lymphoplasmacytic villitis that is very destructive due to trophoblast necrosis and the perivillous space has a “dirty background” of fibroinflammatory debris. (Fig 8,9) Inclusions can be seen and readily identifiable by immunostains for HSV1/HSV2.

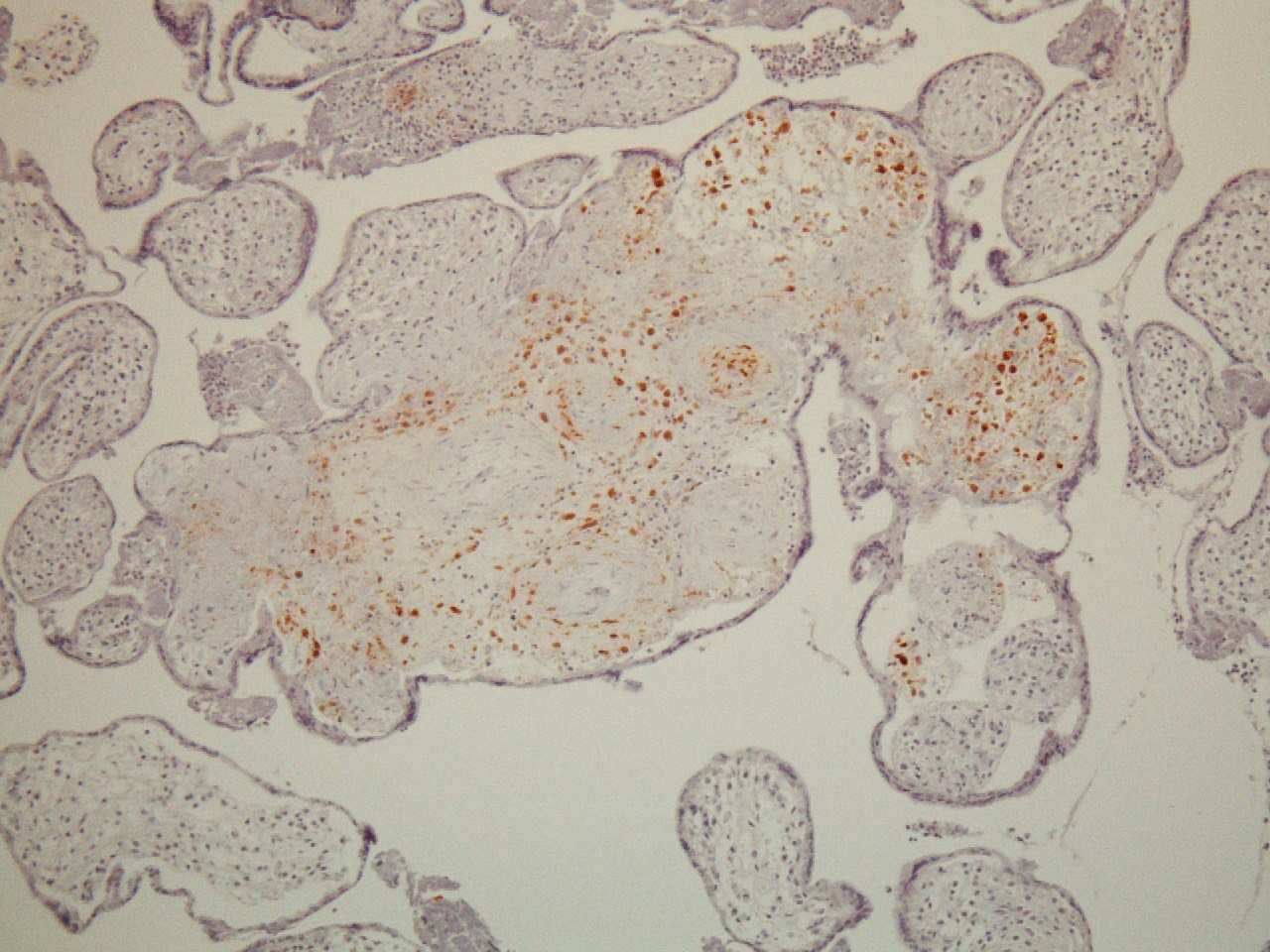

(Fig10) The amnion can show amniocyte viral cytopathy with multinucleation and inclusions and HSV immunostains are positive. They were uniformly negative as were immunostains for CMV, toxoplasma, and treponemes. However these infectious agents also result in a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, and (D)Toxoplasma in particular is quite destructive.(FIG 11) The tachyzoites can be seen in the perivillous space and in the villi.

Pseudocysts with bradyzoites are detectable in the villi (Fig 12)but are much more easily seen in the umbilical cord due to the hypocellularity of Wharton’s jelly; immunostains for Toxoplasma are very useful since the pseudocysts are often sparsely scattered. (B) Massive chronic intervillositis (MCI) is characterized by diffusely distributed loose aggregates of mononuclear cells in the perivillous space (e.g. in the maternal space) (Fig 13 ), and rarely shows any villous infiltrate or villitis. Perivillous monocytes are strongly CD68+ and plasma cells are very uncommon.

MCI is more often seen in cases of spontaneous abortion is important not to miss in cases of first trimester abortus material (e.g., products of conception.) It has a very similar immunophenotype as VUE, but it has a much higher rate of recurrence, IUFD and fetal IUGR (rates of IUGR are 5x those of VUE.) Recent studies indicate that MCI and VUE represent different stages of one disorder with alloimmune basis. (E) Listeria monocytogenes is characterized by an acute villitis and intervillositis, and chorioamnionitis.

Gram positive rods can be seen in the membranes and in the villous microabscesses. The inflammation can be so severe that it results in confluent sheets of neutrophils in the perivillous space with extension to the villi, which are grossly recognizable as pustular lesions on cut surfaces of placental parenchymal sections. It is associated with consumption of unpasteurized milk products, but can also be a contaminant of deli meats and packaged meat products, and poorly washed vegetables and fruit. The woman is at risk for Listeriosis but the placental pathology did not support this as the primary or even a co-pathogen.

References

- Khong TY, et al. Sampling and definitions of placental lesions: Amsterdam Placental Workshop Group Consensus Statement. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016 ;140:698–713.

- Labarrere CA, et al. Chronic villitis of unknown etiology and massive chronic intervillositis have similar immune cell composition. Placenta. 2015;36:681-6.

- Nowak C, et al. Perinatal prognosis of pregnancies complicated by placental chronic villitis or intervillositis of unknown etiology and combined lesions: About a series of 178 cases. Placenta. 2016;44:104-8.

- Heller DS et al. Placental massive perivillous fibrinoid deposition associated with Coxsackie virus A16- Report of a case and review of the literature. Ped Develop Pathol. 2015;19:165-8.

- Chen A, Roberts DJ. Placental pathologic lesions with a significant recurrence risk - what not to miss! APMIS 2017 Dec 22. doi: 10.1111/apm.12796. [Epub ahead of print]

Case contributed by Ona Marie Faye-Petersen, M.D., Anatomic Pathology, UAB Department of Pathology