|

Gorgas Case 2019-02 |

|

|

The following patient was seen in the outpatient clinic of the Infectious Diseases Department of the Hospital Cayetano Heredia during the Gorgas Diploma Course.

|

History: A 58-year-old previously healthy male farmer, states that 1 month prior to presentation, while working with wooden logs, he embedded his left thumb with a spike. The site ulcerated and started draining and in subsequent days, he noted the presence of multiple nodules and erythema in the left forearm. Lesions were small, nodular and painless with spontaneous suppuration in some. He received a course of oral antibiotics followed by a topical anti-fungal cream without any improvement.

Epidemiology: Born and resides in Ancash (highlands) with recurrent trips to Lima. He works as a farmer and breeds several animals including dogs, cats, cattle, pigs, chickens, guinea pigs. Past medical history is non-contributory. Physical Examination: A small ulcer with spontaneous serous drainage is present in the left thumb. Erythema and edema of the left thumb and thenar eminence are shown [Image A]. In the lateral left forearm, there are several erythematous subcutaneous nodules [Image B], some of them are painful and crusted. Laboratory: Hemoglobin 14g/dl; WBC 6500 with normal differential; Glucose 90 mg/dl, normal liver function tests.

UPCH Case Editors: Carlos Seas, Course Director / Carlos McFarlane, Associate Coordinator UAB Case Editor: David O. Freedman, Course Director Emeritus / German Henostroza, Course Director |

|

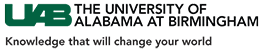

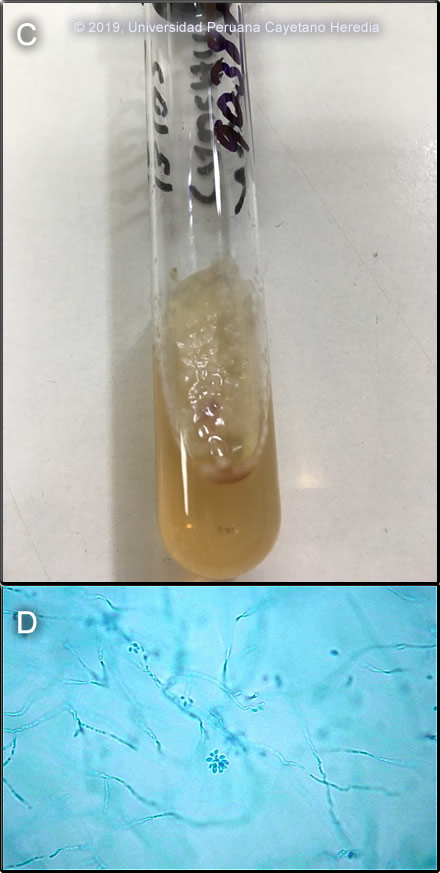

Diagnosis: Lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis due to Sporothrix schenkii

Discussion: Sporothrix schenkii was cultured [Image C] from an aspirate of one of the nodular lesions on the left forearm and from the border of the ulcer. The colonies are moist and glabrous, with a wrinkled and folded surface, pigmented colonies can be seen from white-cream to black. A sample of the colonies showed the typical characteristic bouquet-like micro conidia [Image D]. In cultures of scrapings, aspirates or biopsy material on Sabouraud’s agar, S. schenkii grows very easily and rapidly when present. Smears or aspirates from the lesions in sporotrichosis are usually negative on direct examination (not done in this case) and no useful serology is available. Giemsa stain from the aspirates was negative for Leishmania, skin test for leishmania (Montenegro´s test) was also negative. Environmental reservoirs for S. schenkii include sphagnum moss (including wood or plants contaminated by moss), decaying vegetation, hay, soil and masonry. Outdoor work including farming, construction, gardening, and having a cat are risk factors [Clin Infect Dis.2004;38(4):529-35 and Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(1):34-9]. Acquisition is generally by local inoculation. Sporotrichosis is distributed worldwide but most cases are reported from the Americas and Japan. Most cases are sporadic or occur in self-limited clusters due to some point source exposure. The area around Abancay, Perú (not where this patient lives) has been, perhaps uniquely, identified as an area where sporotrichosis is not only entrenched but is hyperendemic with annual incidence rates of up to 60 per 100,000 population [Clin Infect Dis.2003;36(1):34-9; Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(1):65-70 and Int J Dermatol 2017;56(10):1037-45]. Guidelines for treatment of sporotrichosis have been released by the Infectious Diseases Society of America [Clin Infect Dis.2007;45(10):1255-65] and are partly based on work from our Institute. The treatment of choice for lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis is itraconazole, and in severe extracutaneous or disseminated disease, amphotericin B can be used. Terbinafine 500-1000 mg po bid has been shown to be effective therapy [Mycoses. 2004;47(1-2):62-8]. Posaconazole is the only newer azole to have good in vitro activity against S. schenckii. Fluconazole at higher doses (400-800 mg daily) has demonstrated some activity for lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis, but voriconazole, ravuconazole and the echinocandins are ineffective against S. schenckii though some are active against other Sporothrix species. In the reality of poor countries, many patients cannot afford itraconazole or terbinafine. The older but still effective mode of therapy with a saturated solution of potassium iodide (SSKI) is still widely used in practice. SSKI and its clinical use has been reviewed [J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(4):691-7] and we have previously demonstrated the utility of once daily dosing in order to increase compliance [Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15(4):352-4]. The mechanism of action is unknown. SSKI can also be used for entomophthoromycosis caused by Basidiobolus and Conidiobolus. In dermatologic practice SSKI can be used for erythema nodosum, nodular vasculitis, erythema multiforme, and Sweet’s disease. The main adverse effects are gastrointestinal (nausea) and the SSKI can be added to larger volumes of water, juice, or milk for administration. Care must be taken to avoid potassium or iodide toxicity in patients on ACE inhibitors or potassium sparing diuretics, in patients with renal disease, and in patients on medications or with conditions making them unable to autoregulate thyroid hormone production. In areas with high rates of iodine deficiency, such as the Andean highlands, the use of this solution can trigger hyperthyroidism (Jod-Basedow disease). This patient was started on itraconazole 200mg/day with a plan for at least 3 months of treatment. |