A rich history of research in the Gulf of Mexico will enable UAB marine scientists to support the environmental recovery following the 2010 oil spill.

|

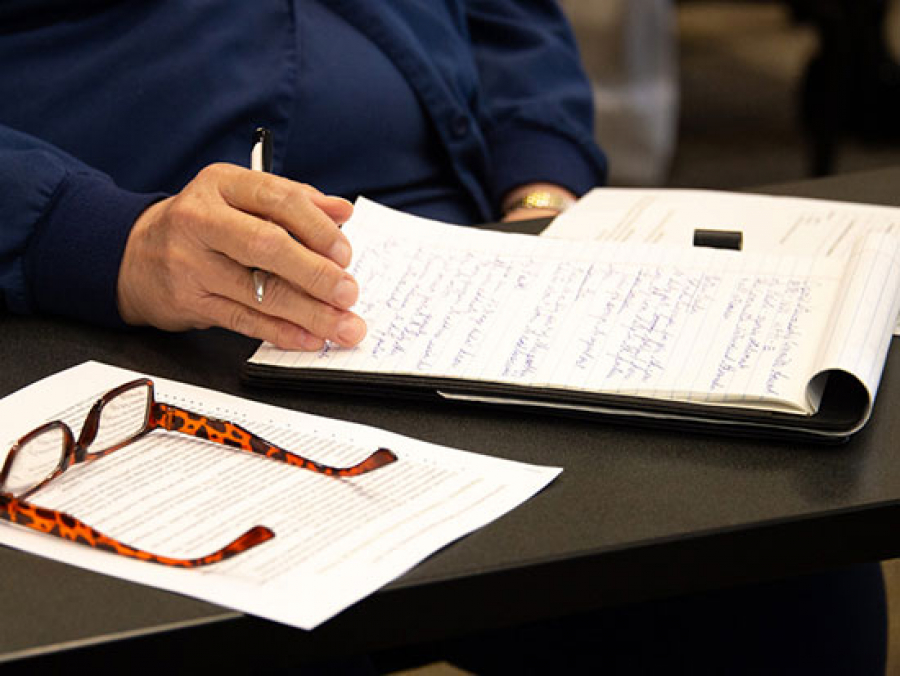

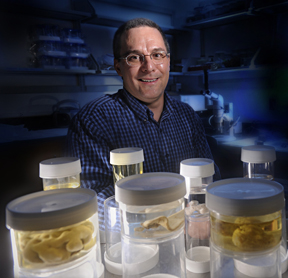

| Associate Professor of Biology Robert Thacker is trying to assess the Gulf oil-spill effect on marine sponges and symbiotic communities. His research is funded by a grant from the Alabama Marine Environmental Science Consortium. |

Thane Wibbels’ conservation and recovery efforts to save the Diamondback Terrapin and Douglas Watson’s work with molting blue crabs are among UAB’s numerous scientific contributions to the coastal ecosystem. Because of this, they and others here now will play key roles in new areas of research.

Nine UAB researchers have been awarded grants from Alabama’s Marine Environmental Science Consortium (MESC) for immediate study of the impact of the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

BP has committed up to $500 million to the Gulf Research Initiative Open Research Program to study its response to the oil spill and the effect on the environment and public health. Of that, $5 million was designated Rapid Response Funds for the MESC, which awards grants to 22 Alabama four-year colleges and universities that comprise its consortium.

UAB researchers have received five MESC grants totaling $217,721, aided by targeted pilot projects funded by the university this past fall. UAB funded 16 research projects to enable investigators to obtain data and prove feasibility for projects in anticipation that new extramural funding opportunities would become available. Investigators from the College of Arts & Sciences and schools of Business, Medicine and Public Health received $308,344 from the Office of Vice President for Research and Economic Development and the deans of the schools that funded the projects.

“Because UAB saw this as a matter of grave concern to the state, we made the decision to invest resources to allow for rapid response,” said Richard B. Marchase, Ph.D., the university’s vice president for Research and Economic Development. “In addition, because of our different areas of expertise we are uniquely positioned to study the long-term consequences of this disaster.

“We are pleased with our initial grants, and anticipate significant additional external funding going forward because of our research capabilities,” Marchase said.

An explosion on the BP Deepwater Horizon mobile offshore-drilling unit April 20, 2010, led to the largest oil spill ever to originate in U.S.-controlled waters. The Flow Rate Technical Group, a group of scientists and engineers from the federal government, universities and research institutions, estimated the amount of oil spilled into the ocean at 4.9 million barrels — or 205.8 million gallons.

How much damage did the oil spill do to the Gulf of Mexico and its ecosystems? No one knows.

Associate Professor of Biology Robert Thacker, Ph.D., and collaborators from the University of Alabama and Auburn University at Montgomery are trying to assess the oil’s effect on marine sponges and symbiotic communities with their $67,781 grant.

They hypothesize that oil and dispersant in sponge tissues alter the species’ composition and the relative abundance of bacteria and invertebrate animals that rely on sponges for shelter and nutrition. Changes in these symbiont communities might indicate the overall health of the sponges.

Thacker’s research team will return to locations sampled several years ago to resample, examine the symbionts and compare them to previous samples.

“If a sponge was exposed to oil, it might have survived, but has its internal community changed? If it hosts 100 species of bacteria, has that community been reduced to two or three species or has the identity of those species changed in some way?

“Our approach is similar to using an indicator species to judge stream quality,” Thacker says. “For example, the abundance and identity of fish species can be used to judge habitat quality and the health of a stream. We’re doing the same thing on a smaller scale by looking at bacteria that live inside sponges.”

Most sponges host a diverse community of bacterial symbionts, which is the smaller of two interacting organisms and is always the beneficiary in the relationship. The larger organism — the sponge itself — may or may not derive a benefit.

In this case, researchers believe the bacterial symbionts may play a role in the physiological processes of the sponge. Some can contribute to carbon or nitrogen metabolism in the sponge, while others can produce the chemical defenses that a sponge uses to protect itself from fish predators.

“Often the roles of the natural bacterial symbionts are unclear, but we do know that there are extremely diverse and unique bacterial communities associated with sponges,” Thacker says.

Nature’s filtering system

Sponges are rarely taken as food by other animals, but crustaceans often lead a parasitic life on them and some mollusks depend on them for their diet. Sponges also act as protective houses for crustaceans, mollusks, small fishes and other sea creatures.

In addition, organisms that live inside the sponge can obtain a rich food supply from the water circulating through them. And that, says Thacker, is one of the most important functions of sponges.

“They’re basically a natural filtering system for the ocean,” Thacker says. “A sponge the size of a gallon milk carton can filter enough water to fill a residential swimming pool every day. Sponges continuously consume the bacteria and other particles found in seawater.”

Thacker says the bacteria living inside of sponges make them interesting creatures to study.

“They’re consuming a lot of bacteria, but then there are bacteria that live inside the sponges that are unique, and they’re not the same as the bacteria that live in the water,” he says. “The big mystery now is the role symbiotic bacteria plays in the overall health and physiology of the sponge host. It will be interesting to see if or how much the oil has affected them, and if so, in what way.”

Thacker expects that the pilot research project will be completed this fall and will provide preliminary data for a larger grant proposal based on these results.

UAB projects funded by the Alabama Marine Environmental Science Consortium are:

• Assessing the impact of oil/dispersant on marine sponges and their symbiotic communities, Robert Thacker, Ph.D. $67,781.

• Chemical dispersants in the marine environment: Harnessing the fish acute phase response for rapid and sensitive evaluation of exposure, Stephen Watts, Ph.D., Alexander Szalai, Ph.D., Vithal Ghanta, Ph.D., Mickie Powell, Ph.D. $25,645.

• Assessing the impact of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on the diamondback terrapin: A top carnivore and keystone species in the salt marshes of Alabama, Thane Wibbels, Ph.D., Ken Marion, Ph.D. $34,395.

• SGER: Studies of microbial communities affected by the Deepwater Horizon spill, James Coker, Ph.D. $60,000.

• Microbial responses to hydrocarbon and dispersant: Lab and field-based studies, Asim Bej, Ph.D. $29,900.